The Mysterious American Tree Sparrow

A frequent topic of discussion on this blog is what we don’t know about bird sounds. Another favorite topic is how amateur recordists might help solve mysteries — and advance science — by recording common birds in their own backyards. Now, as most of North America languishes in the middle of a deep, dark winter, I’d like to point out a golden opportunity for citizen science — a chance to answer questions about a bird that many people know, but few really understand.

I never used to pay much attention to American Tree Sparrows. In the places I lived, they weren’t common enough to be really familiar, but they weren’t rare enough to be noteworthy either. For the first couple of years that I recorded bird sounds, I made no particular effort to record them, even though they can be found in winter with ease not far from my house. I just didn’t think they had much to say.

Boy, was I was wrong.

In fact, American Tree Sparrows appear to have one of the most varied vocal repertoires of any sparrow. I’ve recorded winter flocks on about a dozen occasions now, and listened to a good number of recordings at the Macaulay Library. The more I listen, the more mystified I become.

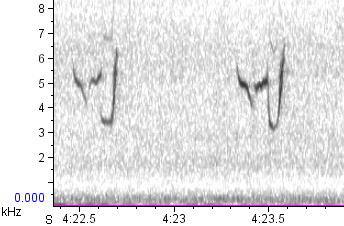

The most distinctive winter vocalization of the American Tree Sparrow is the “flock call,” described by many authors as a two- or three-syllabled musical note:

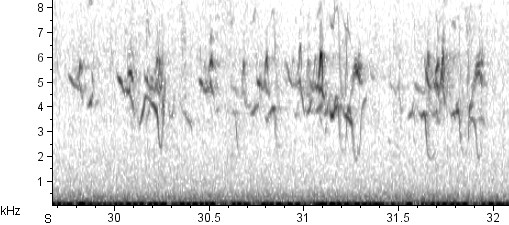

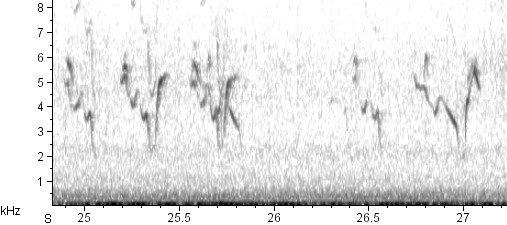

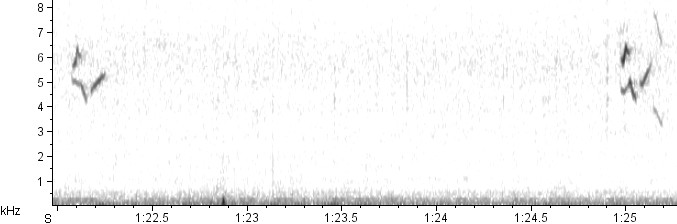

In and of itself, I find the flock calls interesting, because they sound so different from anything I hear from other sparrows, and because the spectrogram shows them to be so complex. But the more recordings of flock calls I made, the more confused I got, because it started to look like no two flocks give the same flock calls:

The incredible variety between individuals (and within individuals) strongly suggests that the flock calls of American Tree Sparrows are learned, not innate. This is interesting and unexpected; as far as I know, complex learned calls are unknown in any of the Tree Sparrow’s close relatives.

Even more interesting is that the limited sample of recordings I’ve studied seems to hint that flockmates give flock calls that are, if not identical, at least broadly similar — while a flock just down the road might sound different. Will further recordings support this observation or disprove it? Either result would raise further questions. Do Tree Sparrows learn their flock calls on the breeding grounds, during migration, or on the wintering grounds? Do they change their flock calls over time? If they learn from flockmates, are flock calls a way of keeping the same group of birds together all winter? If so, why? What happens when a bird with a different kind of call joins a flock?

At first glance, the situation surrounding these complex, apparently learned calls bears more resemblance to the vocal repertoires of some cardueline finches than to the vocal repertoires of any other North American sparrow. Unraveling the entire mystery would be a good dissertation topic for some motivated doctoral student in ornithology.

But I’m short on motivated doctoral students at the moment. Here’s my question: can amateur recordists get a start on solving these questions? I’d like to find out.

If you’ve got recording equipment and ready access to American Tree Sparrows, I challenge you to get out and make some recordings of your local flock.

- Take notes out loud while you are recording (not the entire time, of course; it’s necessary to let the birds speak uninterrupted for at least part of the recording). In your notes, mention the date, the location, the weather, and the species — and most importantly, try to say what you observed the birds doing, and which sounds correlated with which behaviors, and which individuals were vocalizing when.

- If you’ve got a local flock that sticks around most of the winter, follow it over time and pay attention to how many birds it includes. Do flocks split and re-merge? Do they stay separate over the course of the winter? If the number of sparrows in your hedge varies from 5 to 50 and back all winter, we can surmise that flocks split and merge.

- Let me know of what you are doing via email. If people actually do this and we collect enough data, we might be able to answer some of the basic questions about these flock calls, and we might be able to put together a paper for publication.

Anybody out there up to the challenge?

4 thoughts on “The Mysterious American Tree Sparrow”

I was listening to ATSPs up in Niagra over winter break and I’ve got to agree with you that their winter repertoire is pretty amazing. Would love to hear them in full breeding-season singing mode sometime!!

Fascinating stuff, Nathan. You make me wonder whether something similar goes on with the “flock calls” of Harris’s Sparrow, those dotted-rhythm couplets they chant before going to roost. So far as I know, the other Zonotrichias don’t have this–just as AmTree appears to be the only member of its genus to give complex flock calls.

Best,

rick

I’m not familiar with the flock calls of Harris’s Sparrow…a sad consequence of the fact that I live in an area where they are never numerous enough to flock! 🙁 I’ll be very interested to find out more about them! Thanks for the note.

Something entirely different but that is obvious when you hear American Tree Sparrows is that there is absolutely NO way that they are Spizellas. Let alone the fact that structurally and biogeographically they don’t fit Spizella either, it makes you wonder why anyone ever put them there. Some molecular work now suggests that indeed they are not Spizellas, and as you would expect from listening to them, are closer to the Fox Sparrow group, which in turn are allied to Zonotrichia-Junco. So much taxonomic information is in bird sounds, even learned bird sounds, that we are only scratching at the surface of what we can learn from recording birds!

Comments are closed.