The Gargling Chickadees

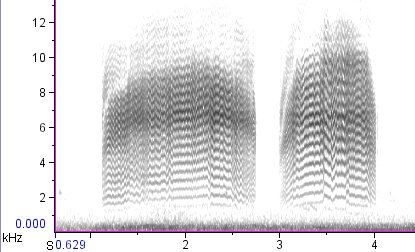

What do chickadees sound like? Why, everybody knows they say “chick-a-dee-dee-dee,” of course.

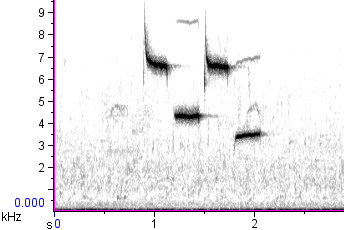

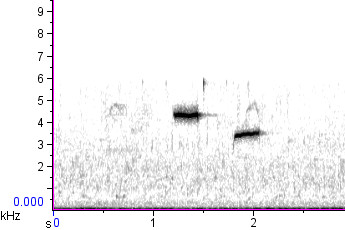

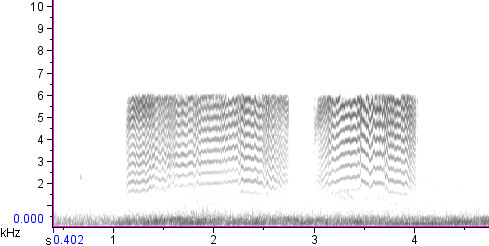

These “chick-a-dee-dee-dees” are what many people (and many books) describe as the “calls” — not to be confused with the “songs,” which are usually understood to be the high clear whistled tunes sung by males in a territorial mood:

All chickadee species give “chick-a-dee” calls, but only three of them — Black-capped, Carolina, and Mountain — have whistled songs. Since these three species are the most widespread and familiar North American chickadees, many people tend to judge other chickadees by their standard. “Lacks whistled song,” many field guides say of Mexican, Chestnut-backed, Boreal, and Gray-headed Chickadees. “No song,” say others, or simply “song unknown.”

But the many researchers who have studied chickadee vocalizations for decades might disagree. As far back as 1981, Millicent Ficken pointed out that an often-overlooked chickadee vocalization called the gargle may actually fulfill more of the traditional “song” functions than the whistled songs.

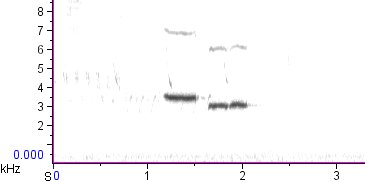

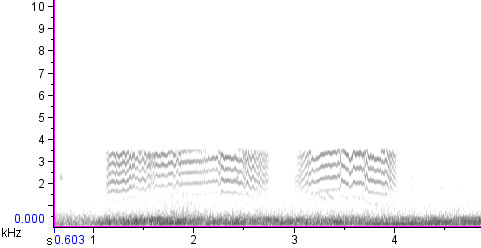

Unlike whistled songs, gargles can be heard from all North American chickadee species. Like traditional songs, gargles are learned; Ficken notes that captive Black-capped Chickadee hatchlings do not develop proper gargles in the absence of an adult tutor. Individual birds typically produce several different types of gargles, forming a repertoire. In most or all species, the gargles are given primarily by males and associated with dominance establishment and territorial defense. They are extremely complex, being made up of many different note types, often with trills and repeated motifs.

For all these reasons, in the species that don’t also whistle, the gargles can be considered “the song”:

Although some field guides may frame them as the outliers, the chickadee species above are not the unusual ones when it comes to the traditional song/call distinction. It’s the whistling chickadees that are unusual, because they have two different kinds of songs — not only whistles, but gargles as well:

The whistling chickadees are a perfect example of how the original “song/call” distinction fails to hold up in many species. Not only can the whistle and the gargle both be called “songs,” but even the “chick-a-dee” calls could be considered songs by some criteria. We should always be suspicious of the many generalizations about birds that we draw from the most common, widespread, and familiar species — remember, they may be the unusual ones.