“Russet-backed” vs. “Olive-backed” Swainson’s Thrushes

The April 2013 issue of Colorado Birds recently hit my mailbox. It’s an excellent issue of a top-flight regional birding journal, and I’m particularly excited about the article about identifying the two distinctive subspecies groups of Swainson’s Thrushes: “Russet-backed” birds from the Pacific Northwest, and “Olive-backed” birds from elsewhere in the range.

(In case you’re wondering about the source of my enthusiasm, I should mention that I not only edit the journal, but also co-authored the article, with the eminent Steve Mlodinow and Tony Leukering.)

I grew up seeing hundreds of Swainson’s Thrushes in South Dakota each spring — all birds of the “Olive-backed” persuasion, though I had no idea of that at the time. When I encountered my first “Russet-backed” Thrush in northern California in 2000, I was certain I was looking at a Veery. The uniform, rich chestnut-brown upperparts ruled out all other thrush species, or so I thought at the time, and it wasn’t until many years later that I realized my mistake.

Over the past decade, the work of Kristen Ruegg and her colleagues has shown that the two forms of Swainson’s Thrush not only look different, but migrate on different schedules to markedly different wintering grounds. They hybridize in a contact zone in British Columbia, but that contact zone is quite narrow, prompting occasional rumors and rumblings of a potential future species split.

One of the proposed lines of evidence concerns differences in vocalizations. And, with some cribbing from the Colorado Birds article, that’s what I’ll be writing about today.

Differences in song?

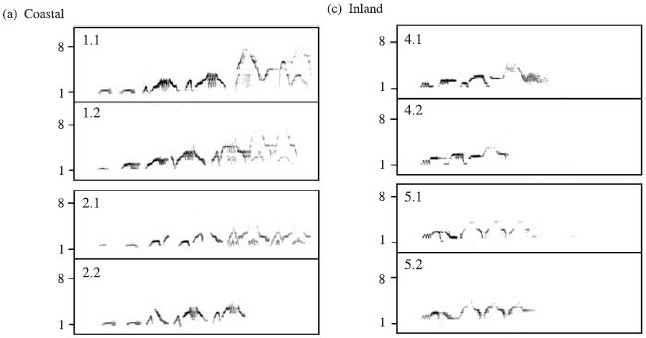

A 2006 study by Ruegg et al. claimed that the songs of “Russet-backed” and “Olive-backed” Thrushes differ in statistically significant ways. The spectrograms in the study seem to indicate some nice obvious differences:

When I first laid eyes on this figure, I thought this ID should be a cinch. The Russet-backed songs in the figure are much longer on average (song 1.1 is just under 2.5 seconds long, while song 4.2 is under a second), and they finish with high, fluting, polyphonic phrases like those in a Veery song, while the Olive-backed songs stay relatively low and simple.

But when I looked at a scattering of songs from across the country, it quickly became clear that these differences did NOT hold up across the species’ entire range.

| “Russet-backed” | “Olive-backed” |

Obviously the Olive-backed songs from elsewhere on the continent seem just as likely to go on longer and end in high, fluting flourishes. I’ve listened to a large number of songs of both species, and I can’t find any way to distinguish them by ear.

To be fair, Ruegg et al. weren’t just looking for differences obvious to the eye and ear — they were performing quantitative analyses based on spectrographic measurements. Even so, they recorded songs from just two coastal populations and two inland populations (plus a fifth population in the hybrid zone). Their results may be due to the differences between the local dialects of these few regions, rather than any larger or more consistent difference between the subspecies groups.

If anybody knows of a way to identify the songs of these two groups by ear, I’d love to hear about it.

Differences in calls

I am unaware of any consistent differences between the “wee?” flight calls of the two subspecies groups, which is a mellow rising whistle rather like the call of the Spring Peeper frog. The “quit”-type contact call, however, does seem to differ slightly on average. Olive-backed tends to give a quick, sharp “quit” that may recall the sound of a dripping faucet or the “whit” of an Empidonax flycatcher. In Russet-backed, this call is often slightly longer and more musical, an obviously upslurred whistle that might be transliterated as “wee” or “pwee,” like a shorter, sharper version of the flight call.

These examples are illustrative:

| “Russet-backed” | “Olive-backed” |

Even this slight difference, however, cannot always be trusted. One recording I found documents a “Russet-backed” from northern coastal California who gives, in between his songs,

- a series of “typical” contact calls of Olive-backed Thrush (1:25 – 1:50);

- a series of “typical” contact calls of Russet-backed Thrush (2:20 – 2:35); and

- a wide variety of “flight calls” (0:37 – 0:43, 2:49, and 3:43 – 3:48).

At least some individual Olive-backed Thrushes give equally variable calls, so caution is in order.

Perhaps the most distinctive vocalization is the alarm call, which is a two-part sound ending in a low, loud, semi-musical purr or chatter. Olive-backed tends to introduce the chatter with a sound like the contact call, “quit-BRRR,” while Russet-backed tends to begin with a much longer and more musical note that is actually more like the flight call: “weee-BRRR.”

| “Russet-backed” | “Olive-backed” |

On the whole, the differences in voice between these two subspecies groups are pretty subtle, and almost never diagnostic, due to extensive variation within each group. I recommend using voice as a supporting character in the field, to be used in conjunction with visual field marks.