A Robin’s Many Songs

Anyone who listens thoughtfully to robins can’t help but bubble with questions about why robins are the way they are.

–Donald Kroodsma, The Singing Life of Birds, p. 37

The American Robin may be the most familiar bird in North America, but for all its abundance and approachability, it remains in some ways inscrutable. Back in 1979, in his classic Stokes Guide to Bird Behavior, Donald Stokes wrote that robin courtship displays remained a mystery, and might not exist at all. The song he called an “enigma,” pointing out that it did not appear to correlate with courtship or territoriality, instead peaking right before the young hatch in any given brood.

Some studies in the 1990s provided evidence that robin song is indeed correlated with courtship and territoriality, but they did not make any attempt to describe the song comprehensively. That task fell to Donald Kroodsma in his popular 2005 book The Singing Life of Birds. Each male robin, Kroodsma explained, has in his repertoire 6-20 simple, whistled “caroling” phrases and 75-100 high-pitched, complex “hisselly” phrases. The familiar daytime song is often made up purely of caroling phrases:

- carol carol carol… carol carol carol carol

But at dawn, the male robin often throws a hisselly phrase in at the end of each strophe:

- carol carol carol hisselly… carol carol carol carol hisselly

In addition, some robins occasionally give long strings of hissellys without any caroling phrases:

- hisselly hisselly hisselly hisselly hisselly hisselly…

Kroodsma documents all this and more; and yet, after fifteen pages of descriptions, explanations, and explorations, he still finishes with more questions than answers:

“Why have two types of phrases, the caroled and the hisselly phrases? Why have a dozen or two of the caroled phrases and a hundred or so of the hisselly phrases? Do other robins count how many a male sings, and if so, is having more songs better in any way? Why are the hissellys used mainly at dawn and dusk? Why at dawn are three or four caroled notes followed by a single hisselly, and what could it possibly mean to sing 71 hissellys in a row?”

The average American probably hears more song from robins than from any other bird, and yet we still cannot answer any of Kroodsma’s questions. Perhaps it is because we do not listen as carefully as we could; and perhaps it is also because what we call “song” in robins is even more complex than Kroodsma’s work has already shown. Today’s post will push the exploration of robin song a little further, in hopes of facilitating the kind of listening (and recording) that could begin to solve the many mysteries surrounding America’s favorite bird.

Caroling phrases

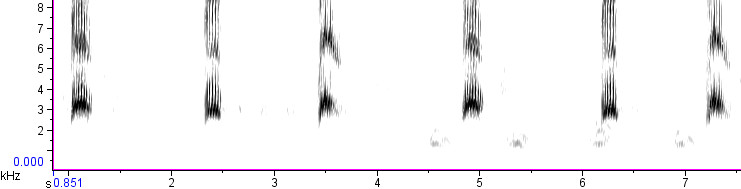

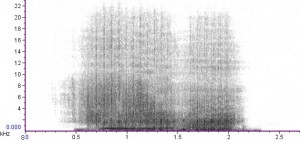

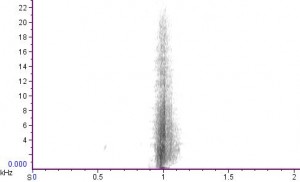

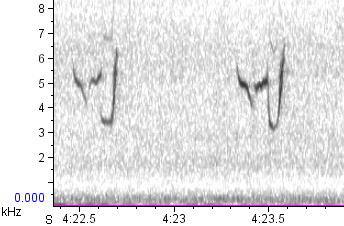

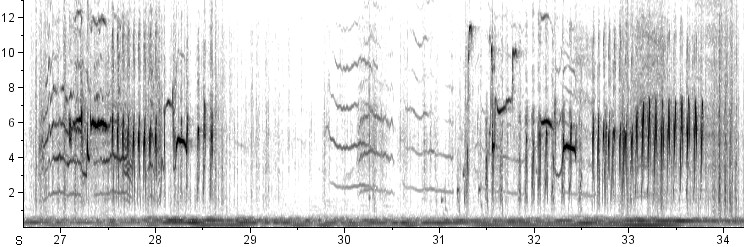

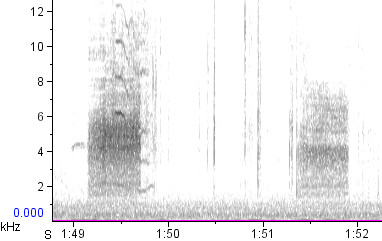

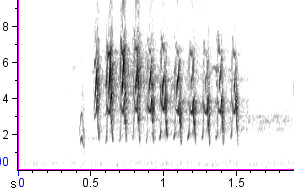

First, here’s an example of the “caroling phrases,” the familiar short, clear, 1-3 syllabled phrases that we often hear during the day:

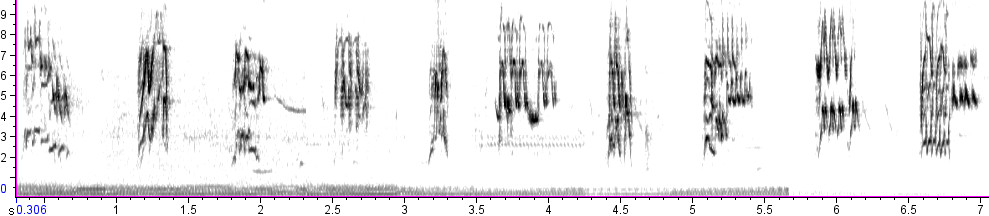

Hisselly phrases

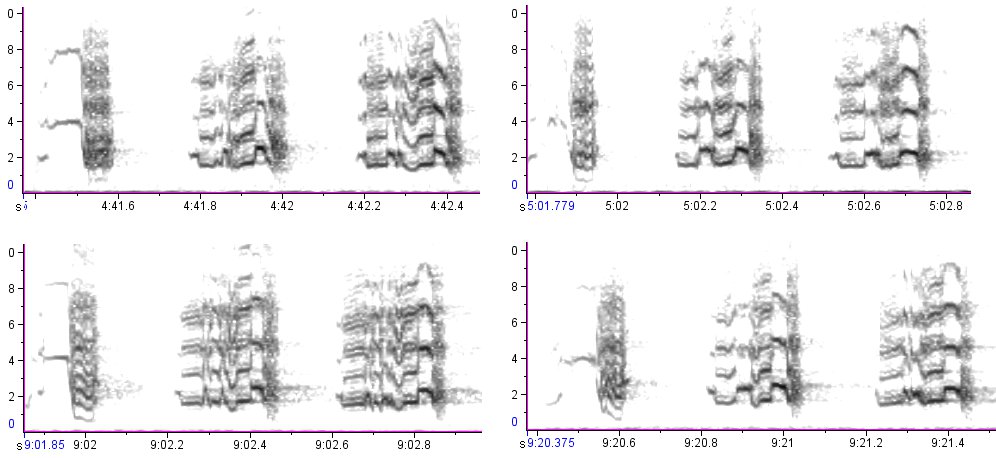

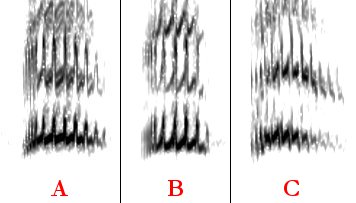

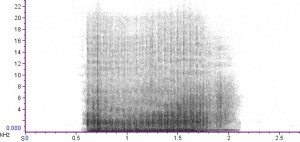

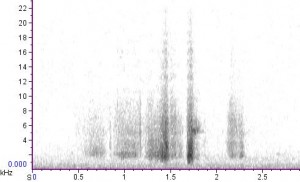

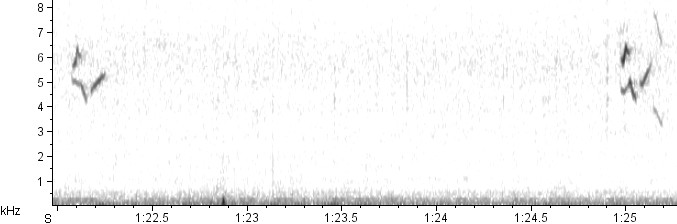

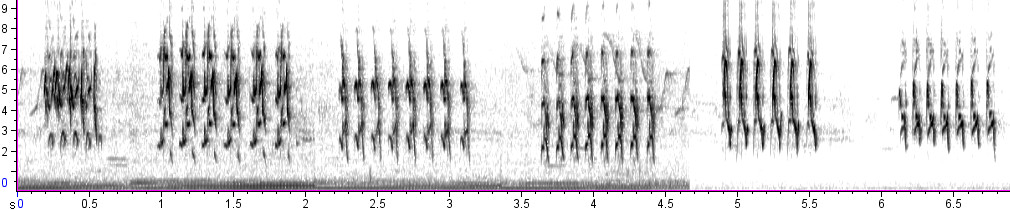

Kroodsma described the hisselly as “an ethereal whispered note much like the delicate flourish at the end of a Hermit Thrush song”. The hissellys shown below, all from the same individual male robin, have been edited together for comparison. Note that they are much higher-pitched and more complex than the caroled phrases, with a great deal more polyphony:

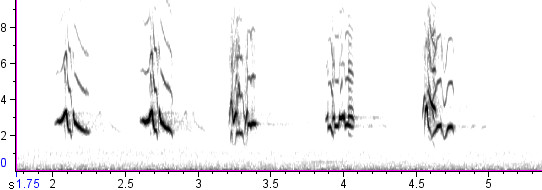

Whinnies

The “whinny” is a familiar call of the robin, often given when the birds are alarmed:

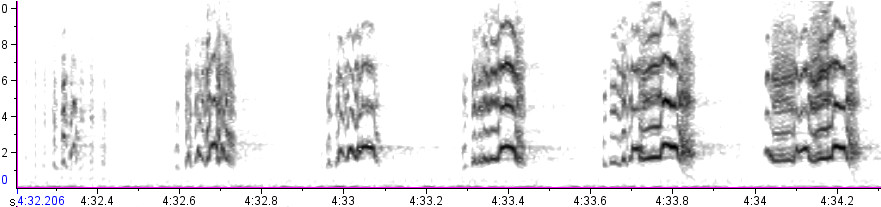

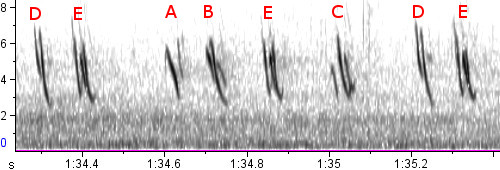

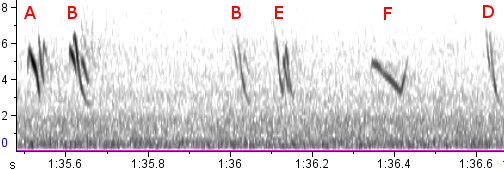

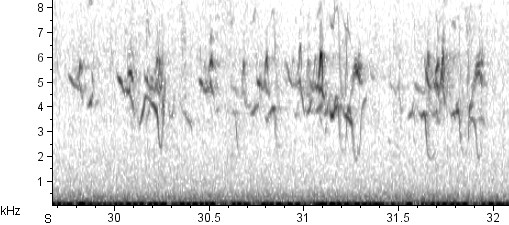

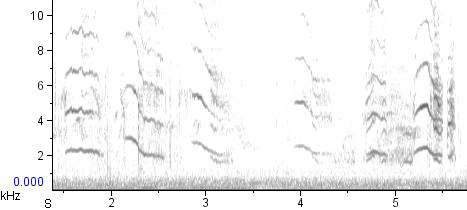

But it’s not just a call. At least at certain times, the whinny (or something much like it) becomes an important component of the robin’s song — and each individual male robin knows an awful lot of different whinnies. Here are six that one male robin incorporated into his song within a two-minute span:

Note the complex and stereotyped fine structure above. These are no mere alarm calls; they are song elements, no doubt about it.

Putting it all together

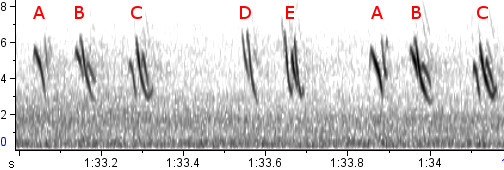

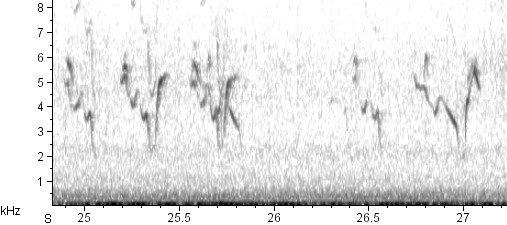

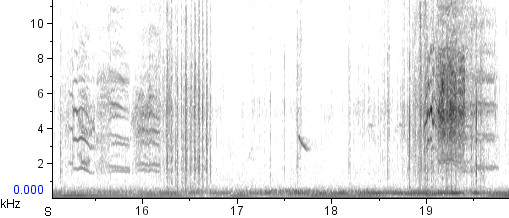

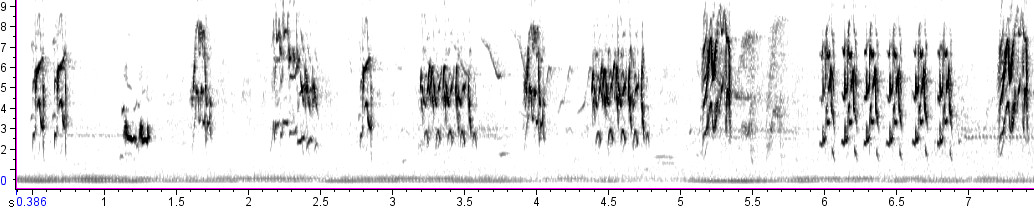

Here’s a confusing recording of a robin singing with carols, hisselys, and whinnies all mixed together — in fact, he is the sole source of all the hissellys and whinnies on the edited tracks above. I recorded him in late May in Boulder, Colorado, and though there were many other robins in the immediate vicinity, none were interacting with this bird that I could see; he was perched up in a tree just belting out his song. What in the world can he possibly be saying?

The beginning of this bird’s song, illustrated on the spectrogram above, follows a pattern like this:

- hisselly (or 2-noted whinny?) carol hisselly hisselly hisselly whinny hisselly whinny hisselly whinny hisselly…

I do not know what is going on with this bird, but its song suggests that anyone seeking to understand robin song should think of the whinnies as a type of song phrase on par with the carols and hissellys. At the same time, it reinforces what you’ve probably already realized: anybody seeking to understand robin song has a lot of work to do.