The Beauty of Spectrograms

I do not count heards. To tick an antpitta is to see one well, otherwise we would have t-shirts with pictures of sonographs.

Iain Campbell

Long before my Earbirding co-author Andrew Spencer went to work for Iain Campbell at Tropical Birding, Andrew introduced me to Iain’s infamous quote about heard-only birds. Being audio fanatics, Andrew and I had a good laugh about it, and resolved to make spectrogram shirts just to spite him.

Someday I will get around to making a T-shirt with a spectrogram on it. But when I do, it won’t be to spite Iain Campbell. Nor will it be to champion the counting of “heards.” (That battle is winning itself — today’s birders are increasingly satisfied with other ways of encountering a bird besides simply laying eyes on feathers.)

When I finally make a spectrogram shirt, it’ll be to celebrate the striking beauty of bird sounds.

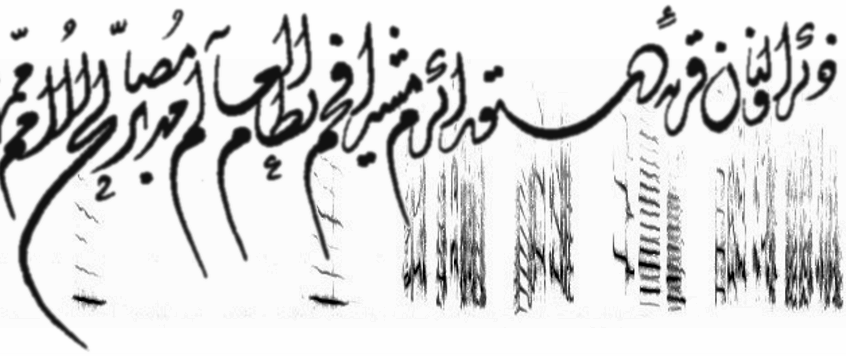

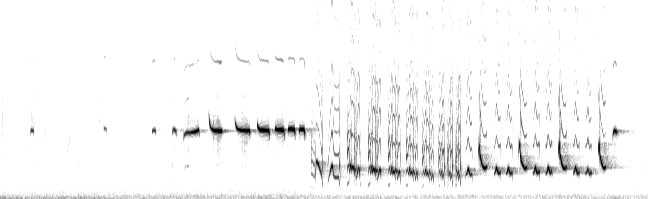

Spectrograms are the calligraphy of the natural world. A spectrogram is text, not in metaphor but in fact. As the written representation of an oral communication, a spectrogram is every bit as valid a text as the words on this page. The lines and curves that make up this sentence are standing in for sounds, as do the lines and the curves in a spectrogram — and in both cases, each line and curve carries meaning to those who speak the language in which the text was composed. The correspondence goes beyond the semantic and into the artistic. Some spectrograms match human calligraphy flourish-for-flourish in intricacy, tension, balance, and grace.

Just as each calligrapher’s work displays its own style, each vocalizing bird traces an individually unique spectrogram when it sings — its own personal signature in sound, the result of a fleeting, even if repeated, intersection of communicator, medium, and meaning. As the Wikipedia entry on Shodo (Japanese calligraphy) puts it, “For any particular piece of paper, the calligrapher has but one chance to create with the brush. … The brush writes a statement about the calligrapher at a moment in time.” In the same way, the spectrogram writes a statement about a bird at the moment it utters a sound.

To celebrate the beauty of spectrograms, I’ve multiplied the images in the header of this blog. Fans of the original Bobolink header need not worry — it’s still in the rotation — but now it’s been joined by seven other spectacular “specs” celebrating a wide variety of bird sounds from different families. One of these eight headers will load at random each time you land on the page. I’ve updated the “Headers” page to reflect this new diversity. If you enjoy them half as much as I do, you might get stuck here hitting “refresh” for hours.

I’ll leave you with two final masterful examples of graphic design, one by a bird and one by a human. I’ll let you sort out which is which.