The Coolest Bird Sound

In the opinion of the late Rich Levad, the Black Swift was The Coolest Bird, and in his still-unpublished manuscript of that name, he advanced a pretty strong argument for its coolness. This is a bird that spends much of its time foraging so high in the air that nobody ever sees it. It nests in the spray zone of waterfalls, so that a juvenile may never have dry feathers between hatching and fledging. And it is poorly understood: to this day we really have nothing but educated guesses as to where the species spends the winter.

It appears that will change soon. My friend Jason Beason of Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory sent me this announcement:

As of the evening of August 24th there are three Black Swifts in Colorado wearing light-level geolocators! On that evening, Kim Potter, Carolyn Gunn, Todd Patrick, Chuck Reichert, and myself caught ten adult Black Swifts using mist-nets in the Flat Top Mountains in western Colorado. The locators were placed on two females and one male, all of which weighed greater than 50 grams (the minimum cutoff to stay less than 2% of total body weight). In just a few weeks the swifts will begin their migration to locations unknown. With string and ribbon included the total weight we added to the birds was only 1.8 grams! With luck, this time next year we will be able to report where these birds spent the winter of 2009-2010. If not for the help of Carolyn Gunn, a trained veterinarian with very nimble hands, we could not have placed these devices on the swifts in a reasonable amount of time. We are very thankful that she agreed to help with this project!

The light-level geolocators that Jason referred to are the same technology used by Stutchbury et al. 2009 to estimate the migratory paths of Wood Thrushes and Purple Martins, birds too small to carry the satellite transmitters like those the Pacific Shorebird Migration Program has placed on Bristle-thighed Curlews and Bar-tailed Godwits in recent years. Jason later reported to me in a follow-up email that a fourth Black Swift was outfitted with a geolocator at Box Canyon, near Ouray, on 29 August. Unlike the satellite transmitters, the geolocators do not send data in realtime; it will be lost unless the birds are recaptured next year and the data downloaded. Since Black Swifts are extremely faithful to their nesting sites, the team thinks there is a good chance they will be able to retrieve one or more of their geolocators a year from now.

One of the reasons Black Swifts are so little known is that they are rarely observed, even near their nest sites. I believe that one of the reasons they are rarely observed is that most people don’t know what they sound like. Unfortunately, one of the reasons why most people don’t know what they sound like is that they’re devilishly difficult to record. Over the past couple of years I’ve found that Black Swifts are actually quite vocal, particularly near the nest — but the nests are usually so near waterfalls that recording is basically impossible.

Thanks to Rich Levad and his army of Black Swift volunteers, the number of known nesting sites in Colorado has more than tripled in the last decade, and at some of these sites, it’s possible to get a reasonable recording. With better recordings comes a greater chance of detecting Black Swifts when they are overhead. I have sometimes been able to find this species by ear when I wasn’t expecting it or looking for it, and I’m not the only one. So let’s spend some time on identification by ear.

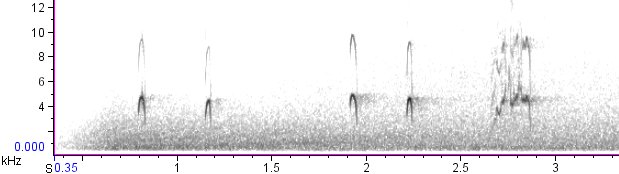

The individual “pip” notes of the Black Swift are extremely similar to the “pips” of Pygmy Nuthatches, and they can sound similar to some notes of Red Crossbill. Rarely, the swifts will make a longer, higher-pitched “squeak” noise.

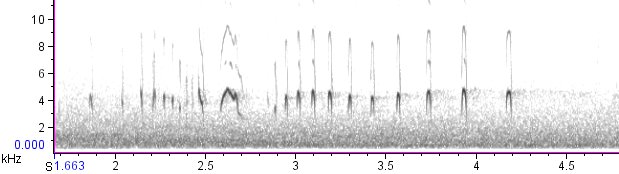

Sometimes Black Swifts give a relatively stereotyped “extended call” that starts with a rapid twittering series of “pips” and culminates in a clear “squeak.” This is often followed by a decelerating series of “pips.”

Black Swift vocalizations in general, and the extended call in particular, appear to be correlated with aerial chases, although all vocalizations are also given by some solo flying swifts and by perched individuals at or near the nest. Nor are these vocalizations limited to the daytime: at least at their nesting sites, Black Swifts will vocalize throughout the night.

You can hear more examples of Black Swift recordings in Xeno-Canto’s collection.

4 thoughts on “The Coolest Bird Sound”

Thanks for this interesting post. I’ve probably seen Black Swifts near their nesting site at Jemez Falls, NM, but the birds were very high in the sky and I was not comfortable listing the species as seen.

Now, armed with the knowledge of their vocalization, and hopefully their cooperation, I’ll be able to identify the species.

Do you know if the birds have already begun to migrate? Do I need to wait until next year to try again?

Bill,

The Black Swifts are remarkably late in their nesting, so chances are that many of their young have not yet fledged. You should still be able to see them in New Mexico. However, they will probably fledge within the next two weeks, and as far as we know, once the young fledge, the entire family heads south immediately. Hopefully the geolocators will give us more information!

Comments are closed.