A Good Quiz

I recommend heading over to RMBO’s audio quiz before the 15th of November…their fourth installment is a good one. Easy to identify to genus, not quite as easy to peg the right species! Best of luck…

I recommend heading over to RMBO’s audio quiz before the 15th of November…their fourth installment is a good one. Easy to identify to genus, not quite as easy to peg the right species! Best of luck…

Jason Beason just informed me of a brand new biweekly audio quiz set up by Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory at http://rmboaudio.blogspot.com. I think this is a marvelous idea. In fact I once harbored aspirations of running an online audio quiz of my own, but now that I actually have the means to run one (via this blog), I find myself reluctant to do it. You can expect an occasional quiz like the one I just ran on crossbills, but I’m not planning on it as a regular feature.

The RMBO quiz will be the only regular, moderated bird sound quiz on the web, as far as I can tell. There are certainly automated quizzes on the web — the Patuxent Bird Sound Quiz is fun — but I don’t know of any other blog-style audio quizzes whose challenges change on a regular basis. Let me know if I’m missing any!

I find it odd that audio quizzes are so rare, but then I find it odd that photo quizzes are so rare also. I disagree with Kenn Kaufmann’s assertion that online photo quizzes are “legion.” It’s quiz photos that are legion, not photo quizzes. Anybody can post a photo of a mystery bird to the web, but it’s rare to find an outlet with the discipline to do it regularly, publish the answers with educational explanations, and keep track of the winners’ scores.

By the standard I’ve just laid out, for my money, the best moderated photo quiz in the world is Mr. Bill’s Mystery Quiz, now known as the Colorado Field Ornithologists Photo Quiz, which was started by Bill Maynard in 2003. The ABA Online Bird Photo Quiz is also venerable, dating from the same year, but it only changes monthly, which means they’ve only published 78 quizzes so far. Mr Bill is run weekly, so it’s on quiz 318, believe it or not! If these are the two best and most regular photo quizzes on the web, can it be coincidence that Tony Leukering is moderating both of them at the moment? The man is remarkable.

In addition to their audio quiz, RMBO is starting a photo quiz as well. The CFO/Mr. Bill and ABA quizzes are geared towards intermediate to expert birders, while both RMBO quizzes are going to serve easier fare. And I think that’s appropriate, especially on the sound side, since I find that sound quizzes tend to be harder than photo quizzes — particularly in the absence of information about the time and place of the recording. I look forward to seeing (and hearing) what they post!

Here are the answers to the quiz from the last post:

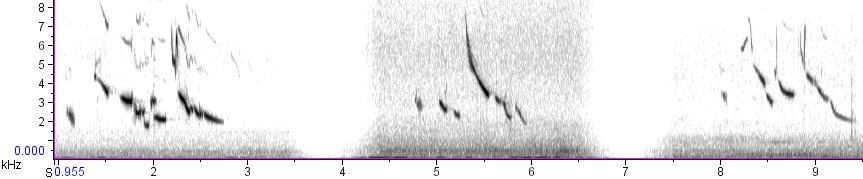

Type 4 is believed to specialize on the cones of Douglas-fir. It is widespread but somewhat irregular in its distribution: it is usually common in moist forests of the Pacific Northwest and can be frequently found in dry forests there also. It is regular in southeast Arizona, and indeed this particular recording was made at Barfoot Junction in the Chiricahuas in May 2009. It appear to be absent some years from Colorado, but fairly common in other years; 2009 saw a decent influx of this type into the state.

Ken Irwin (unpubl.) has proposed that hidden inside Type 4 there is another call type, Type 10, that specializes on sitka spruce in coastal California. It’s still unclear to me whether Type 10 is a separate call type or just a variation on Type 4. Whatever the case, Type 10 seems to wander widely, at least across the northern states, out to New England and Maryland.

The Type 4/10 group, as a whole, sounds very distinctive because of its upslurred calls. It may be a little hard to hear that they are upslurred because they are delivered so fast, but the rising, flicking quality of the calls is pretty distinctive, reminding some people of the “whit” calls of Empidonax flycatchers.

This type is sedentary and restricted to the South Hills and Albion Mountains of Idaho, where it feeds on the local variety of lodgepole pine. It sounds kind of like Type 2, clear, simple, and downslurred, but it is noticeably low-pitched. I think it is kind of “dull-sounding,” without much ring or resonance, but I’d be interested to hear how other people describe the difference. I recorded this in the South Hills in September 2009.

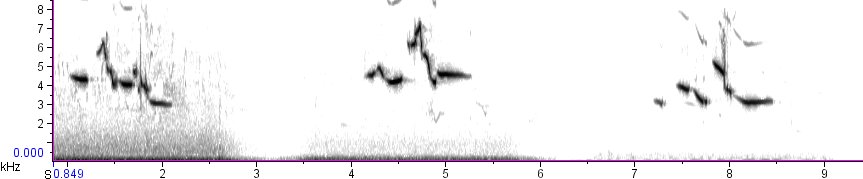

Here’s a Type 2. This is probably the most numerous crossbill in North America; it is common almost everywhere Red Crossbills can be found. It is surmised to specialize on ponderosa pines. Across its range its calls are variable, but the high-pitched, clear, downslurred quality is fairly distinctive. This recording was made in Boulder County, Colorado, in July 2007.

This is one of the smallest crossbills (only Irwin’s proposed Type 10 is similarly small) and is one of the most common crossbill types in moist northwestern forests, apparently specializing on western hemlock. It also can be found across the boreal forest, occasionally into New England, and it wanders rarely into the southern Rockies — there are now two certain records for Colorado and more in the “probable” category. There are also recordings from Arizona.

Types 3 and 5 sound similar to my ear: they are more complex than the types we heard above, less clear and less obviously upslurred or downslurred. Type 3 is the duller-sounding of the two, but I must admit I need practice with this identification. This particular recording, the second-ever for Colorado (from the Grand Mesa, February 2009), was made by Andrew Spencer when I was right beside him–and I didn’t turn on my microphone because I thought they were “just” Type 5s. To be fair, Andrew recorded them because he thought they were White-winged Crossbills. 🙂 He didn’t identify them until days later when he looked at the spectrogram.

This is the “other” common crossbill in Colorado (besides Type 2), a widespread bird of high elevations in the West, apparently adapted to feed on lodgepole pine but also very fond of Engelmann spruce. In direct comparison I think it sounds more “metallic” than Type 3, but it’s a tough call in the field. A distant flock can sound a lot like a bunch of crickets. This recording was made in Larimer County, Colorado, in June 2009.

Interest in “Lilian’s” Meadowlark has spiked with the publication of Barker et al. (2008), which found significant genetic differences between Lilian’s and other “Eastern” Meadowlarks and recommended that Lilian’s be elevated to species status. Naturally, I keyed right in on the following quote:

Cassell (2002) found significant differences in the songs of Eastern and Lilian’s meadowlarks. However, given the learned nature of song in this group (Lanyon 1957), and the sharing of unlearned call notes between these forms (Lanyon 1957, 1962), the relevance of this observation with regard to species limits remains an open question.

A couple of months back I ordered Cassell’s (2002) thesis through interlibrary loan, to judge the evidence for myself. Overall, I found some aspects of the work very useful, but other aspects quite questionable. In particular, I have two complaints:

Despite these issues, Cassell does convince me that Lilian’s songs average significantly lower in frequency than Eastern songs, in agreement with the descriptions in Sibley’s field guide. Cassell says:

In the field, the astute listener may recognize the primary song of S. m. lilianae by its overall lower pitch than that of S. m. magna.

So far, my experience indicates that this statement holds true in most (but not all) cases. Lilian’s song is frequently, but not always, low-pitched enough that it sounds like Western Meadowlark in tone quality (although the pattern of each song is still much more like Eastern than Western). In addition, it seems to me that Eastern Meadowlarks frequently end on a drawn-out, nearly monotone clear whistle, while Lilian’s tend to end on a whistle that is much more downslurred. There is a lot of overlap in the final note type, so caution is warranted, but I think the combination of terminal inflection and, especially, overall pitch (perceived largely as tone quality) should identify most Lilian’s Meadowlark songs.

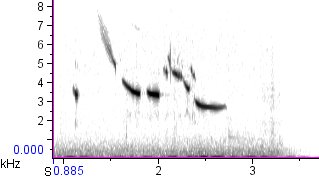

A few weeks ago in Arizona I was able to record a few Lilian’s Meadowlark songs:

The first songtype, with its low pitch and its complex middle section, is particularly reminiscent of Western Meadowlark, but all three above seem fairly typical of Lilian’s. Note the downslurred endings.

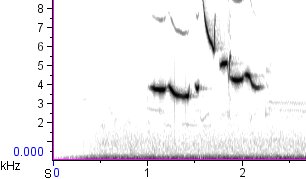

For comparison, here are three typical songs of Eastern Meadowlark. Note the more “ringing” monotone endings (characterized by more horizontal lines on the spectrogram) and the relatively high pitch (lowest frequencies about 3 kHz, as opposed to 2 kHz for Lilian’s):

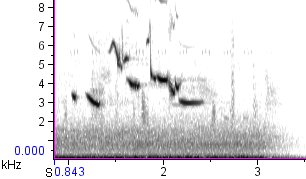

If all songs of both forms fit these patterns, field identification would be pretty easy, but sometimes the birds will throw you for a loop. Here’s a Lilian’s that sounds more like an Eastern on account of its high pitch and monotone ending:

And here’s a Eastern that sounds something like a Lilian’s on account of its relatively low pitch:

And, of course, not all Easterns have the ringing monotone ending:

For a little more ear practice, check out this wonderful repertoire remix of 19 different Lilian’s Meadowlark songtypes, all recorded by Andrew Spencer on 6/1/2009 from one individual bird in Eddy County, New Mexico. You’ll notice that about half the songtypes end in a ringing monotone whistle, which seems to be a slightly higher percentage than among the birds I recorded in Arizona.

To hear more Eastern Meadowlarks, check out Xeno-Canto’s collection. The Macaulay Library has plenty of Eastern Meadowlark songs also, and even a few Lilian’s.

All right, let’s find out how well this works. Here’s a remix of three meadowlark songs. Which ones are Eastern and which are Lilian’s? Leave your guesses in the comments field, and I’ll post the answers in a couple of days.