A Bicknell’s Thrush Critique

{We interrupt our series on describing bird sounds to bring you this special post.}

In 1995, in the 40th Supplement to their checklist, the American Ornithologists’ Union recognized Bicknell’s Thrush (Catharus bicknelli) as a full species, splitting it from the Gray-cheeked Thrush (Catharus minimus) on the basis of “differences in morphology, vocalizations, habitat preferences, and migration patterns.” In support of these differences, they cited two papers: Ouellet 1993 and Evans 1994.

The split came under fire earlier this year in an extensive Xeno-Canto forum discussion that focused mostly on the vocal evidence. Dan Lane gave a rather scathing assessment of Ouellet’s 1993 paper; Andrew Spencer testified that both Bicknell’s and Gray-cheeked respond to playback of one another’s songs, in contradiction of one of Ouellet’s key claims; and I made comments critical of Evans’ 1994 paper, which described differences in the nocturnal flight calls.

Recently, the conversation was joined by Bill Evans himself, the author of the 1994 paper. In case you don’t know, Bill Evans is one of the great bird investigators of our age — one of the prime movers behind the last few decades’ resurgence in the study of nocturnal migration. In his Xeno-Canto comment, Bill presented a detailed defense of his paper. I promised to respond when I got a chance.

I have great respect for Bill Evans and what he’s taught all of us about birds and their sounds, but I’d like to reassess the evidence and arguments in his 1994 paper. In my opinion, that paper simply did not present strong evidence for a consistent difference in flight calls between Bicknell’s and Gray-cheeked Thrushes. And yet many have cited it as though it did, not least the AOU when it split the two species. I’d like to get people thinking about this paper more critically. Hence this blog post.

Evans’ original case

You can read Evans’ paper online for yourself, but I’ll summarize it here in a nutshell.

- Bill Evans collected a number of recordings of nocturnal flight calls of apparent Bicknell’s/Gray-cheeked Thrushes, from Minnesota, Alabama, west-central New York state, and Florida.

- He noticed that the Florida calls tended to have a much earlier peak and a higher maximum frequency than the calls from the other three locations (with little to no overlap, according to his table). In other words, he detected two discrete types of “Gray-cheeked-like” flight calls.

- He argued that Bicknell’s Thrush would be expected to migrate directly through Florida, but that only “regular” Gray-cheeks were likely in the other three locations.

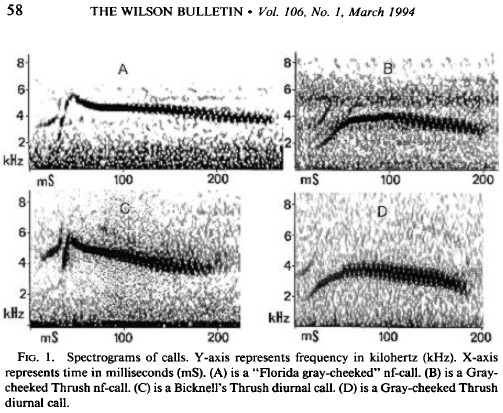

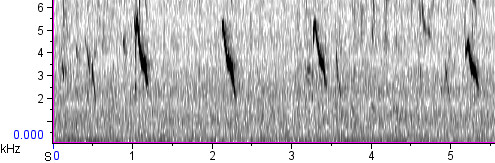

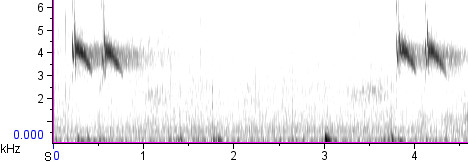

- He found a daytime recording of a Bicknell’s from Mount Mansfield in Vermont that was a close match for one of his nocturnal Florida calls, and a daytime recording of a Gray-cheeked from Manitoba that closely matched one of his nocturnal calls from outside Florida. Here’s the figure he used to illustrate this point:

And by virtue of the evidence above, he argued that the nocturnal flight call of Bicknell’s Thrush differs consistently from that of Gray-cheeked Thrush.

When I first read this paper, I found it reasonably convincing, mostly because of Figure 1. The top-to-bottom similarities and left-to-right differences are obvious, and they tell a clear story. It’s an excellent piece of visual rhetoric (and I say that admiringly, as a teacher of scientific writing and rhetoric).

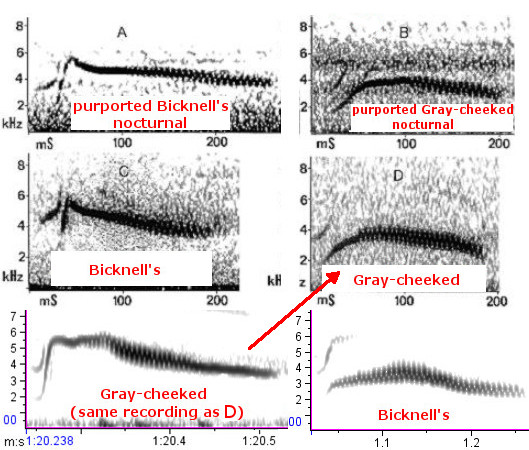

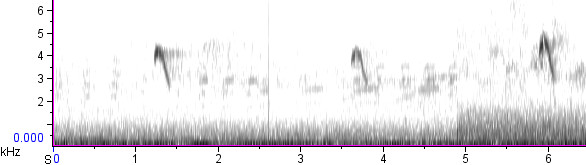

But as I started to research the vocal repertoires of Bicknell’s and Gray-cheeked Thrushes for my field guide project, I realized that Figure 1 is far too simple, far too neat. The daytime calls of Gray-cheeked and Bicknell’s Thrushes are extremely variable. So variable, in fact, that if you pick the right recordings, you can construct an alternate version of Figure 1 from Evans 1994, with the two species switched:

Bill said both in his 1994 paper and again in his Xeno-Canto comment that he couldn’t find any Gray-cheeked daytime calls that matched his purported nocturnal Bicknell’s, and he couldn’t find any Bicknell’s daytime calls that matched his purported nocturnal Gray-cheekeds. Well, these look pretty darn close to me. The Gray-cheeked call at lower left is a pretty good match for the early-peaked shape of the purported Bicknell’s at upper left, and it’s got almost exactly the same peak frequency. It’s from the exact same Churchill, Manitoba recording as the one Evans used to create the daytime Gray-cheeked spectrogram “D” (the high, early-peaked call occurs at 1:20, while the “D” call is either the one at 1:26 or the one at 1:36).

Meanwhile, the call at lower right is from one of Andrew Spencer’s recordings of Bicknell’s Thrush from New Hampshire. Note the “buffalo-humped” shape and the peak frequency all the way down at 4 kHz.

So both species can give high-frequency, early-peaked calls during the day. And both species can give low-frequency, late-peaked calls during the day. So why couldn’t they both give both types of calls at night?

The migration-route argument

Evans 1994 argues that Bicknell’s would be expected to migrate through Florida at the time of his recordings, but never discusses whether Gray-cheeked Thrush might also pass through at that time. But Gray-cheeked appears to be more common than Bicknell’s as a migrant in Florida. A 2005 paper by Glen Woolfenden and Jon Greenlaw found that of 54 Florida specimens, 47 were Gray-cheeked Thrush, and only 4 were Bicknell’s (with 3 remaining unidentified). Eleven of the Gray-cheeked specimens were from eastern coastal counties, and Woolfenden and Greenlaw could find no differences in migration dates. A similar situation seems to exist in other southeastern states: Lee (1995) re-examined 24 specimens taken in North Carolina and found that 23 were Gray-cheeked and only 1 was Bicknell’s.

The sheer number of Gray-cheeked specimens from Florida (even eastern Florida in May) suggests that the peninsula is a regular migration route for at least part of the population. And the ratio of southeastern US specimens suggests that in migration, Gray-cheeks outnumber Bicknell’s throughout the region. Gray-cheeked winters in northern South America from Columbia east to Guyana — largely south and east of Bicknell’s wintering range on Hispaniola — and Gray-cheeked is reportedly a “trans-Gulf migrant” (according to BNA, etc.). All of this suggests to me that any given Gray-cheeked-or-Bicknell’s flight call recorded in Florida is more likely to be from a Gray-cheeked.

Evans 1994 reports only high-pitched, early-peaking flight calls from Florida, but Bill’s Xeno-Canto comment indicates that subsequent sampling there has turned up low-pitched, late-peaking flight calls as well. He wrote, “you don’t get a regular stream of “buffalo humped” GCTH calls in the mid-eastern Florida coast in May unless you have a sustained period (typically 2 days or more) of westerly winds. And there is nowhere else I’ve found in eastern US where one can record a pure set of the higher pitched, steadily descending GCTH calls like those I’ve recorded from eastern FL in May.”

This is an interesting claim. I’d expect Gray-cheeked Thrushes breeding in Quebec and Newfoundland to pass through Florida even when winds weren’t westerly. The situation Bill describes is consistent with a scenario in which the high-pitched, early-peaking flight calls are given by eastern Gray-cheeks, while the low-pitched, late-peaking flight call is the hallmark of the western Gray-cheek, with Bicknell’s either unrepresented in the sample, or overlapping eastern Gray-cheeks. At the very least, I don’t know how Bill can rule such a scenario out.

Also, the phrases “a regular stream” and “a pure set” ring my alarm bells. They suggest that “irregular streams” and “impure sets” — such as the odd “Gray-cheeked-type” call on a non-westerly Florida wind, or the odd “Bicknell’s-type” call outside the range of Bicknell’s — might be dismissed as “atypical,” resulting in unwitting confirmation bias. (More on the dangers of the word “atypical” here.)

Daytime call variation

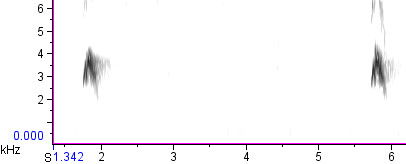

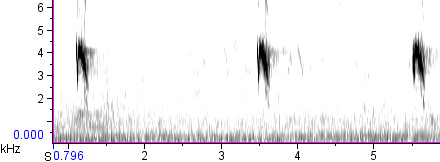

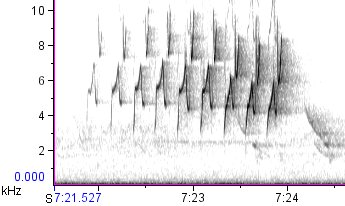

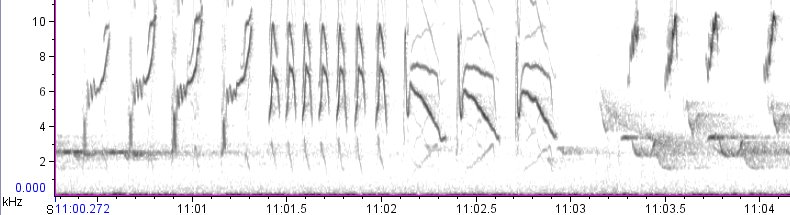

I’ve put together two animated spectrogram GIFs to show how the daytime calls vary in individual Gray-cheeked and Bicknell’s Thrushes. They both loop at 10 frames per second.

Both GIFs are at exactly the same scale: the top of the graph is 6 kHz. Notice how peak frequency changes, as well as call shape. No call forms are exactly shared, but some are strikingly similar.

Notice, too, that the calls don’t vary at random. Birds of both species repeat the same call many times in a row. Then they either switch immediately to a different call type, or transition into the new type via 2-3 intermediate calls. The Gray-cheeked uses four different call types in this sample; the Bicknell’s uses five. If we had longer recordings, it’s likely we’d hear more call types from each individual: recordings and various published reports put individual call repertoires at up to 10 in both species (e.g., Ball 2000). And repertoires of neighboring birds tend to be similar, as evidenced by recordings and reports of call matching by neighboring birds. But across the geographic range, these calls vary greatly; Marshall (2001) found a huge variety of call forms across the continent.

These locally-similar but regionally-different repertoires of call notes vary in a pattern like that seen in Red-winged Blackbirds and Lapland Longspurs, and the pattern strongly suggests that the burry daytime calls of Gray-cheeked and Bicknell’s Thrushes are learned, not innate. If the calls are learned, then regional differences would be expected to arise over time, in exactly the same manner as song dialects. Some call types might be heard less often in one population and more often in another; some might become exclusive to a particular area. Gray-cheekeds breeding in, say, Quebec or Newfoundland (and migrating through Florida) might use higher-pitched, earlier-peaking calls with greater frequency than Gray-cheekeds breeding farther west.

And this raises several questions. If each individual thrush knows 5-10 different daytime versions of its burry calls, which one (or ones) does it give during nocturnal migration? Or is the night flight call completely separate from the daytime calls? Is it innate or learned? Do individual birds have repertoires of night flight calls, or is there just one per bird? When we see variation in nocturnal calls, how much of it is individual, how much of it is dialectal (that is, geographic), how much of it is repertoireal (I just made up that word), and how much of it is due to mere plasticity?

These questions matter, and right now we don’t know the answer to any of them. Even if we know the answers to these questions for other species, it may not be safe to assume that Gray-cheeked and Bicknell’s are the same. After all, among North American Catharus thrushes, only Veery shares their trait of having not just one daytime flight-call-like sound per individual, but a repertoire of such calls.

Conclusion

Based on all the research I’ve done, I have a hunch that during the day, Bicknell’s is indeed more likely on average to give the higher-pitched, early-peaking calls, while Gray-cheeked is indeed more likely to give the lower-pitched, later-peaking calls. But the overlap seems pretty much complete, and I suspect that few, if any, nocturnal call forms are diagnostic for one species or the other. Remember, in bird identification, it’s not enough to find a match; you have to rule out other potential matches. If Gray-cheeks are capable of making the Florida-type calls, then how do we know they didn’t? How do we know the higher-pitched, early-peaking calls aren’t more common in eastern populations of Gray-cheeked? How do we know that the existence of two call forms in Florida isn’t an artefact of limited sampling?

I’m perfectly willing to believe that Bicknell’s and Gray-cheeked Thrushes do differ in nocturnal flight calls. I’m even willing to believe there’s little overlap. But if I’m going to believe it, I need some evidence more solid than anything I’ve seen yet.