Bohemian Rhapsody

I can still remember the first time I saw a waxwing. I had only been birding for a year or two, and I had already picked out Cedar Waxwing as one of my most wanted birds. I was six at the time, and I did most of my birding with my grandmother, either on Long Island (where I lived at the time) or in western Massachusetts (where she had her house). We had searched for waxwings several times, to no avail, so I was overjoyed when I first laid eyes on them.

It took far longer for me to come to grips with their larger cousins, Bohemian Waxwing. By then I knew enough to pay attention to how birds sounded, and I can still remember the high-pitched, tinkling trill they let out, so different from Cedars. And then that was all I ever heard from them, every time I saw one. It’s a gorgeous sound from a gorgeous bird, but would it hurt for them to throw a little variation in? It turns out that waxwings have some of the simplest repertoires of all passerines, with no true “song”, or at least none that has been documented. And even their calls are typically variations on the same trill.

Or so I thought. This past summer I was privileged to be able to spend a lot of time recording in the far northern parts of North America. Among the many species I was hoping to target was Bohemian Waxwing, on the vague theory that they must have more than just that trill call, and if they did I would be most likely to hear it on the breeding grounds. At first I was rather frustrated. I found waxwings aplenty, but they just would not cooperate! Unlike in those big, practically tame flocks I was used to from irruption years in Colorado, Bohemian Waxwings in the taiga were quiet, shy, and rarely in groups larger than three or four birds.

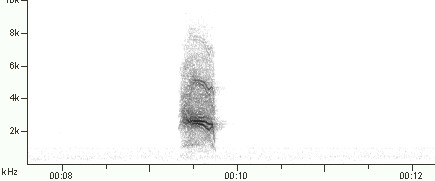

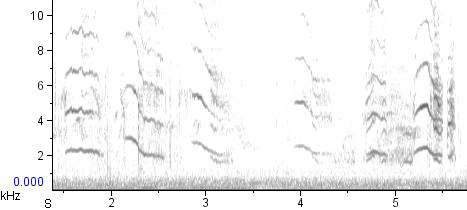

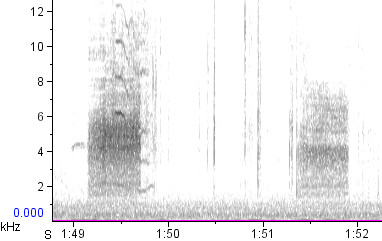

But then I lucked out. I was driving along the Nabesna Road in eastern Alaska when I heard the distinctive trill of a Bohemian Waxwing out the window. I worked my way into the stunted black spruce muskeg and was rather surprised when I found a pair of birds that were much less shy than I had come to expect. The reason why became apparent a short while later when I saw one of the birds carrying nesting material to a spruce tree. “Here it is,” I thought, “my chance to record some different vocalizations!” And with that in mind I stood behind a nearby spruce and trained my mic on the birds as they built their nest. But as I sat their recording them I was more and more disappointed – they occasionally gave either long or short versions of their normal trill, but nothing different. It wasn’t until I listened to a cut I made where both birds landed together at the nest site that I heard a barely audible, amazingly variable sound unlike any I’d ever heard from Bohemian Waxwings before. Jackpot! That eureka moment recording (and a photo of the bird making it) are linked below:

I then carefully snuck out of the bog. I was going to pass by the Nabesna Road again in about a month, and I had the perfect setup waiting for me. If (and it’s always a big if with nesting birds) the pair of waxwings didn’t abandon the nest, and nothing predated the young, I’d have a “captive audience” on my return trip to see what else waxwings can say.

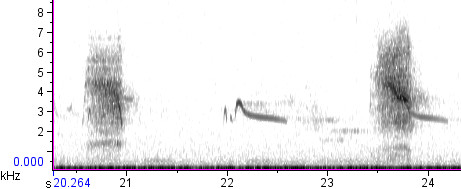

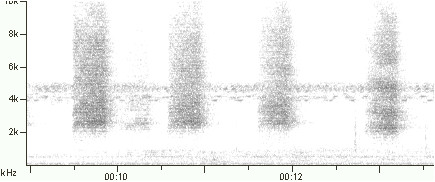

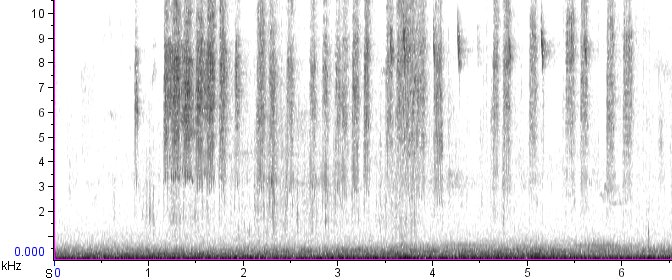

From that first observation of the pair I noticed several things. First, the birds had both very short (only a few notes) and more normal long versions of their trills, and they seemed to serve different functions. The long trills, what I consider the classic Bohemian Waxwing call, were typically given at long intervals and most often when a bird took off from an exposed perch. The short trills, on the other hand, were given much more frequently, often by a bird perched prominently on a spruce tree, both when the other member of the pair was present and when it had flown off. Playback of the long call either elicited no response, or the bird flew away, whereas the short call would bring the bird in close, and at times even low. My suspicion is that the short call serves some kind of territorial purpose, but even after watching the birds for a long while I am not entirely sure. Examples of both the long calls and short calls are here:

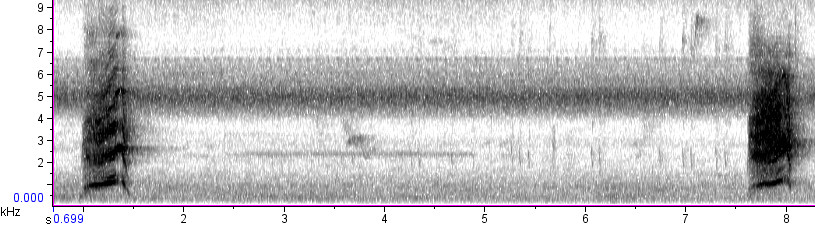

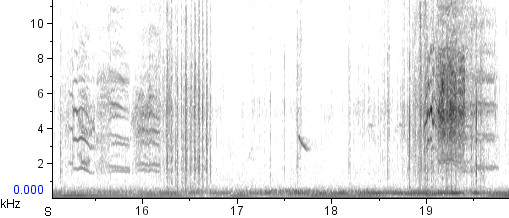

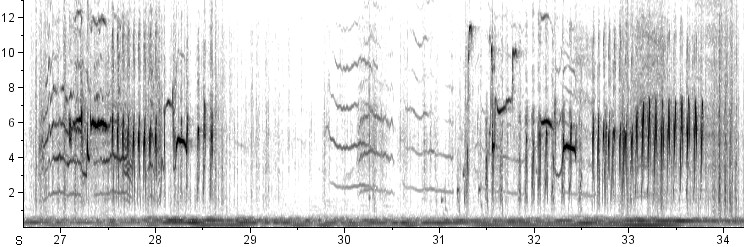

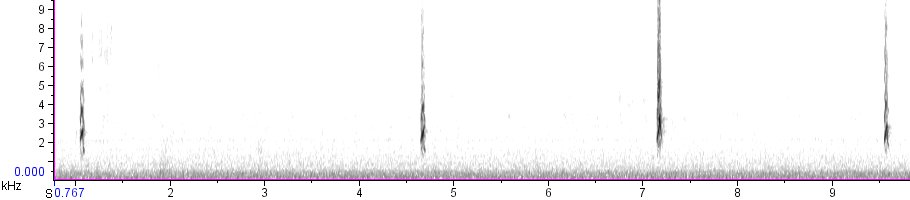

Fast forward a month, and I was back on the Nabesna Road. I was ecstatic to find that the nest was still there, and four well-feathered young were looking healthy and alert in it! Before I even got into position to record the nest I got a good recording of another, completely different vocalization – a very high-pitched, clear, descending whistle, very much like the “seer” call of a thrush. This was clearly an alarm call, given at my presence, though the birds quickly calmed down and resumed their normal behavior. I was beginning to wonder if that’s all the waxwings would do in alarm when a passing band of Gray Jays decided to drop in. Boy did the waxwings take offense at that! One of the birds outdid itself in driving off the offending jays, giving two more alarm calls while at it. The first, given only twice an apparently in extreme alarm, was a harsh, low-pitched growl. This was quickly followed by short trills that, while higher-pitched than the growl call, were significantly lower-pitched than their normal trills. Some loud bill snapping was also thrown into the mix, making for quite the varied repertoire of alarm sounds! You can hear both the clear whistle call and the other alarm sounds below:

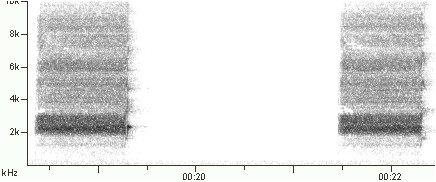

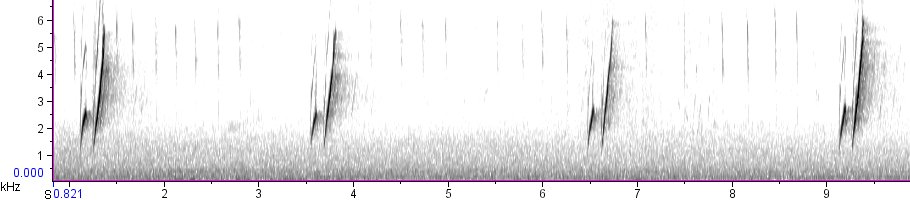

Once everything had returned to normal I took the opportunity to record the young begging. Compared to the alarm calls the adults gave these calls were rather boring, essentially just a noisy version of the adult trills. That recording is linked below:

The time I spent with Bohemian Waxwings this past summer was near the top of my list of highlights for my trip to Alaska. But even with everything I recorded from them, I think there is still more to be captured. A few winters ago my friend Ian Davies heard what may actually be a stereotyped song from the species (something that has never been described or recorded) that:

“sounded almost like the pattern of a White-winged Crossbill song but with the calls of a Bohemian Waxwing…a longer sustained note of the standard musical rolling note, on one pitch, for maybe 1-1.5s, and then changing without stopping to another pitch, all of this with the standard clipped musical quality”

So there’s clearly more to discover about waxwings – a chance for anyone with a mic, or even an iPhone, to document something new if they’re in the right place at the right time!