Subsong vs. Whisper Song

Imagine a male robin, treetop in the early morning, belting out his song for all the world to hear, announcing his territory at the top of his avian lungs. It’s an easy thing to imagine. In fact, it’s pretty close to the stereotypical image of a singing bird.

Now picture that same male robin, deeper in the foliage this time, singing a song somewhat reminiscent of the usual treetop carol, but far, far quieter — so quiet, in fact, that it can’t be heard at 50 yards, and so subtle that the bird doesn’t even open its bill to sing, a slight fluttering of its throat the only clue to the source of the ventriloquial melody.

If you listen carefully to birds at close range, you’ll find that quiet, complex vocalizations like these are not uncommon. Often, they are called “whisper songs.” Some more technically-minded birders might call them “subsongs.” Both subsongs and whisper songs are fascinating, but they are not the same thing. Let’s look at the similarities and differences.

Subsong

The term “subsong” has meant a number of different things since it was first coined in 1936, but I have generally thought of it as The Sound Approach described it:

Subsong…is usually given from dense cover, is often full of mimicry, and may bear little resemblance to familiar adult songs. […] Subsongs are typical of birds with a low sexual motivation, for example adults and first-year birds before the breeding season really gets started, or juveniles after it has finished.

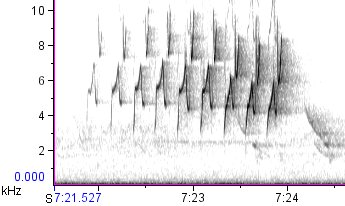

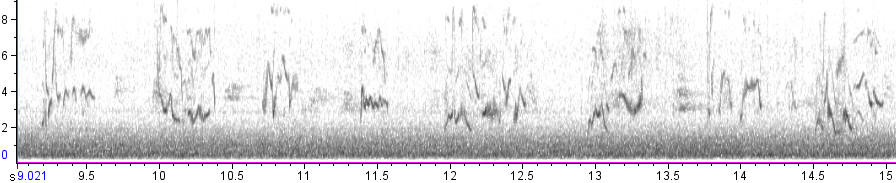

In January and February, the flocks of American Robins that descend into the fruit trees around my home provide ample opportunities to hear and study subsong. I have never made an attempt to age the birds I have recorded, so I can’t comment on whether the subsongs of juveniles and adults are different at this time of year. (Intuitively, I believe that they should be different, since the avian brain changes as birds mature, but I have no evidence for this at present.) What seems certain is that almost every robin in these flocks will sometimes get into the sub-singing mood:

Compare the spectrogram above with the spectrograms of American Robin songs that I posted a few weeks ago, all of which were recorded in April, May, or June. The January phrases appear more similar to “hisselies” than to “caroling” phrases, but they’re not a perfect match for either one. Nor are they perfect matches for each other — they’re poorly stereotyped. Add that to the extremely low volume, from a bird that doesn’t even open its bill, and you’ve got what appears to be a classic subsong — either the practice sounds of a juvenile that hasn’t yet learned to sing, or the “warmup” tunes of an adult whose neural song circuitry has atrophied over the winter, in the absence of breeding hormones.

The general theory about subsong is that the bird isn’t producing stereotyped phrases because it can’t — it either hasn’t learned how yet (as a juvenile) or it’s physiologically unprepared (as an adult outside breeding condition). Like the babbling of infant humans, subsong provides a window into the process of vocal learning — a complicated, fascinating, messy process that, in a few short months, will result in the crisp, polished performances we know as adult song.

Whisper Song

The term “whisper song” has an even longer history than “subsong,” dating back at least to 1896, when Olive Thorne Miller wrote in the Atlantic Monthly:

A catbird at my back, too happy to be long still, would take courage and charm me with his wonderful whisper song, an ecstatic performance which should disarm the most prejudiced of his detractors.

The phrase appears to have crossed into the ornithological literature as early as 1914, with J. William Lloyd’s letter to Bird-lore titled “The Whisper-Song of the Catbird”:

The performance was like that of a bird in a reverie — like the ghost of a thought of a song. His throat merely trembled, and occasionally the bill parted just a trifle. Yet his song seemed the full repertoire of the Catbird.

Lloyd’s letter seems to have occasioned numerous other published observations of “whisper singing” in other bird species and at other times of year (e.g., Shafer 1916). Quickly, the notion of a “whisper song” gained broad currency among people interested in birds — mostly, it seems, in reference to the same phenomenon we just described as subsong.

I prefer to restrict the term “whisper song” to another kind of quiet, complex vocalization — one that isn’t heard from juveniles or non-breeding adults, but rather from birds at a peak of sexual excitement.

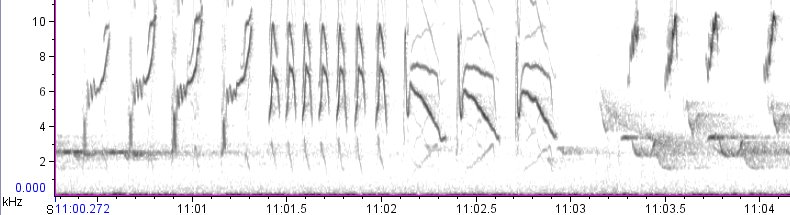

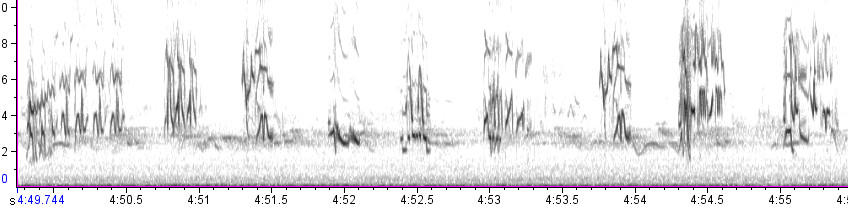

Note how different this whisper song is from the subsong above. For one thing, it matches the “hissely” phrases we’ve seen from other spring robins. The level of vocal control is much higher; the bird repeats patterns with precision. For example, both the first and second phrases in the spectrogram include elements that are repeated exactly. And the whole third and seventh phrases are carbon copies of one another. This demonstrates that the bird is remembering particular phrases and re-deploying them at intervals, which means that these phrases form a repertoire, a library of remembered behaviors. This robin isn’t “making it up” as he goes along. He isn’t subsinging. He’s singing.

The Sound Approach described such singing as “highly motivated, sexually charged, and ultra-crystallized,” typical of male birds in close-range courtship situations. Indeed I have heard these whisper songs from male robins only during the breeding season, usually in the presence of females — and when no females were visible, I have suspected their presence. This is an entirely different phenomenon than off-season subsong, and it needs a different name. For now, “whisper song” seems like a good way to describe these complex, quiet vocalizations — the avian equivalent of whispering seductively into your sweetheart’s ear.