Recyclers

“Mockingbirds are among the world’s most inspired mimics,” writes composer Andrew May. “They learn to imitate other birds’ songs (and other sounds) and incorporate them into their song. Humans, too, imitate and recycle the sounds we hear into our own songs and stories; technologies for recording and manipulating sound have made us even more avid recyclers.”

I like thinking of mockingbirds and other birds that imitate as “recyclers” rather than “mimics,” and so do some biologists. It’s been argued that using the term “mimics” to describe mockingbirds is misleading, because in most branches of biology, “mimics” are organisms that take on or use the characteristics of other organisms in order to be mistaken for them. The palatable Viceroy butterfly, for example, profits from its similarity to the poisonous Monarch only if predatory birds can’t tell the difference. It may not be clear why a mockingbird chooses to belt out the song of a Carolina Wren, but everybody agrees that it isn’t trying to pass itself off as a wren; more likely its motives are closer to those of a human hip-hop artist who creates remixed songs entirely from samples. It’s not mimicking, it’s “appropriating,” to use biologists’ favored term — or “recycling,” to use Andrew May’s analogy.

But May is not content merely to comment on the artistic motives of mockingbirds. He has turned the tables on the mockingbird and “recycled” its already-remixed song into an artistic statement of his own.

May, an associate professor of music at the University of North Texas, has composed a piece of avant-garde classical music called “Recyclers” that centers on a recording of a Northern Mockingbird that I made in Big Bend National Park in 2007. I had forgotten that I gave him permission to use the recording until recently, when I stumbled across his website devoted to the composition. I’m quite taken with it.

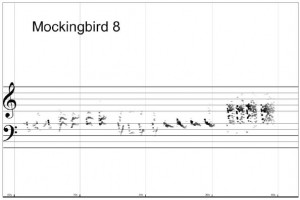

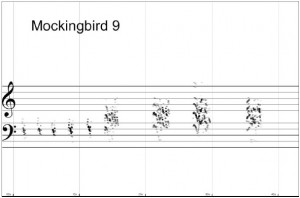

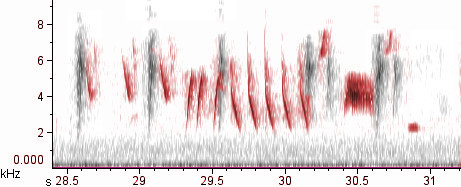

The part of the piece I find most fascinating is that May didn’t even use traditional musical notation. Instead he overlaid a spectrogram of the mockingbirds’ song directly onto the musical staff:

I’ve often felt that my own musical training was very helpful in learning to read spectrograms, and I’ve seen people use spectrograms of bird songs to recreate them in musical notation, but this is the first time I’ve seen anyone merge spectrograms and musical notation in this way.

In a live performance, the slowed-down mockingbird sings along on a digital recording while the performers attempt to imitate it, using their ears and their interpretation of the unorthodox score as a guide. It’s not Beethoven, and those unaccustomed to modern classical music may find it unappealing. But I, personally, enjoy it quite a bit. You can listen to a 25-minute performance by the Nova Ensemble below:

As May points out,

The performance may happen anywhere – a concert hall is not necessarily the best environment. Outdoor spaces (especially those populated with mockingbirds) are encouraged.

Wouldn’t it be wonderful to hear a chamber orchestra inviting the local mockingbird population into a joint performance? Unfortunately, the slowed-down playback of the bird sound in May’s recording means it’s unlikely to get a mockingbird’s attention even if performed outdoors — they won’t recognize it as mockingbird song. But knowing mockingbirds, it might not matter. Perhaps they’ll learn something, and repeat a piece of May’s mockingbird-inspired music long after the chamber orchestra is gone.