George the Sparrow

Ian Cruickshank of Victoria, BC sent me a remarkable recording of a very confused Song Sparrow, which seems to be incorporating the complete song of a Northern Waterthrush into its own singing. Here’s the recording on Xeno-Canto:

When I first heard the recording, I thought the bird could be a juvenile using some imitations in its subsong — a decent possibility, given the late September date — but the comments Ian sent me about the recording seem to rule that out:

I first heard this Song Sparrow giving this song phrase in April of this year; I didn’t manage to record it at the time and it was a stroke of luck that I came across it again, engaged in a territorial match with another male Song Sparrow, belting out this song in the exact same location, in September this year. Obviously it’s a resident bird.

Let’s compare spectrograms. Here are a couple of excellent recordings of Northern Waterthrush songs. Note that waterthrushes, like Song Sparrows, have numerous song dialects across their range:

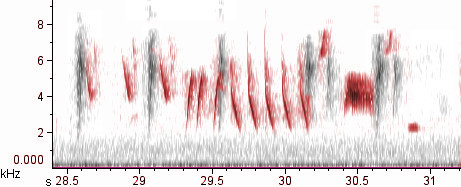

Here’s a spectrogram of one strophe of Ian’s weird Song Sparrow. Because the other birds on the recording make the spectrograms difficult to read, I’ve highlighted the Song Sparrow song in the background by coloring it red (a la The Sound Approach):

The last four (red) notes on the spectrogram are pure Song Sparrow, but boy, the rest of it sure looks like Northern Waterthrush, with the classic pattern of three contiguous series, including the rapidly downslurred whistles at the end. I think it’s highly likely that this Song Sparrow, during the “critical period” in which it was listening to the songs around it and piecing together its repertoire, mistook a Northern Waterthrush for a legitimate Song Sparrow tutor. This phenomenon is rare in Song Sparrows, but not unprecedented. Here’s what the Birds of North America account has to say about it:

Species displays innate preference for learning con-specific song and, like other Emberizidae, rarely mimics other species. Song Sparrows exposed to natural Song and Swamp Sparrow song in lab preferred strongly to learn conspecific song, but sometimes sang syllables of Swamp Sparrows (Marler and Peters 1987, 1988). Song Sparrows fostered by canaries (Carduelinae) did not mimic foster parents in one study (Mulligan 1966) but copied some elements in another (Kroodsma 1977). In contrast, Eberhardt and Baptista (1977) suggested Song Sparrows imitated Wrentit (Chamaea fasciata) syllables in wild, and Baptista (1988) recorded a Song Sparrow in San Francisco, CA, that produced White-crowned Sparrow song; another bird at Tioga Pass countersang White-crowned Sparrow song with neighbors of that species (M. Morton pers. comm. in Baptista and Catchpole 1989).

Song acquisition has been pretty well studied in Song Sparrows, and we know a lot about how they put together their repertoires. When they are raised in the laboratory with adult tutors of their own species, they usually tend to copy whole songs verbatim. They also prefer to copy the songs that are shared by multiple tutors — in other words, they seem predisposed to learn the most popular local tunes. However, some Song Sparrows act differently; one bird invented all its own songs, and several others tended to recombine elements from multiple tutor songs in creating their repertoire. Ian’s sparrow most likely did the latter: it was trying to invent a new Song Sparrow song using elements of other Song Sparrow songs it had heard, but it misidentified one of its tutors and ended up with a weird, chimeric melody.

Now that it is an adult bird, it’s likely to sing this hybrid songtype for the rest of its life. It’s hard to say whether that will disadvantage it. Various studies have measured Song Sparrows’ responses to abnormal songs (including, among others, artificially constructed songs that arranged Swamp Sparrow syllables according to Song Sparrow syntax, and vice versa), and the findings tend to agree that imitations or corruptions of Song Sparrow songs elicit weaker responses than typical songs, but they still elicit responses. Thus, this abnormal song likely won’t be as effective in driving away a rival male or attracting a female mate, but it may get the job done. If, like most Song Sparrows, this individual has between 5 and 13 different songtypes in its repertoire, then the weird waterthrush-song might only be deployed between 8% and 20% of the time. Assuming it’s the only abnormal songtype in the repertoire, it might not prove a huge disadvantage to the singer.

If this bird maintains a territory over multiple years, there’s a chance that juvenile Song Sparrows moving into nearby territories might even select it as a tutor, adding some or all of the Northern Waterthrush syllables to their own songs second-hand and potentially propelling them into the local Song Sparrow vernacular in the long term. A similar process might explain why, for example, so many of the “Thick-billed” Fox Sparrows in the Sierra Nevada end their song phrases with what appears to be a straightforward imitation of the “kleer” call of Northern Flicker:

However, I think this unlikely to happen among Vancouver Island Song Sparrows. Song Sparrows seem much less likely to imitate than Fox Sparrows, which means Songs probably have a stronger (though not ironclad) genetic mechanism to guide young birds to ignore the syllables of other species and incorporate only their own. My prediction: this wrong-singing sparrow might not be a complete pariah, but in the long run he probably won’t prove a strong competitor for territories and mates either, and his borrowed syllables are unlikely to impress the next generation to follow in his footsteps. He’s a slightly socially inappropriate, oddball schmo: the George Costanza of Song Sparrows. We’ll call him George for short.

4 thoughts on “George the Sparrow”

Wow, fascinating bird. I think I would be rendered speechless if I witnessed this out in the field.

Thanks for an educational posting Nathan. A question for interested readers out there: With how much certainty can we say that this is indeed an imitation? How do we know that this Song Sparrow didn’t make up this phrase on its own, and it just happens to very closely resemble Northern Waterthrush song? It’s probably impossible to know the origins for sure, especially with a species that shows such a great deal of variation in vocalizations and song acquisition, but I’d be interested in anyone else’s thoughts on probabilities, one way or the other.

I think it highly unlikely that the resemblance is a coincidence. I’m not sure I can quantify the likelihood, and you’re certainly correct that it’s impossible to know for sure, but I feel confident in saying that there’s no way that the first part of this sparrow’s song is anything other than an imitation of a Northern Waterthrush.

Ian’s question is interesting. Bewick’s Wren can sound like a Song Sparrow at times. Is that an imitation taken up a long time ago and now incorporated in the wren’s vocabulary, or did it just make the phrase on its own and it just happens to resemble a Song Sparrow? Not something we can really know, I guess, but it did make me wonder that if other birds were impressed with George’s songs perhaps in a few centuries this song type might be a prevalent dialect in the area–future birders might then classify the Victoria Island (or west coast) subspecies of Song Sparrows as sounding like a Northern Waterthrush (as Bewick’s Wren sounds like a Song Sparrow).

On another note, this summer I saw a Wilson’s Warbler and a Northern Waterthrush engaged in what appeared to be counter-singing in the Hudson Bay lowlands. The waterthrush was giving the last part of its song and the warbler’s song sounded “richer, fuller” so it was more akin to the waterthrush’s sound. I’m hoping their possible duel wasn’t a one-time thing and that we managed to capture it on one of our Song Meters.

Comments are closed.