The Vowels of Birds

In my 2007 article in Birding magazine, I distinguished three methods of describing a bird sound in words: transliteration, analogy, and analytic description. But the article was so focused on promoting the third of those methods that it gave the other two short shrift. I was particularly scathing in my condemnation of phonetic transcription, bemoaning its “limited capacity to carry information,” with “little or no regard to pitch, tone quality, variation, or any other crucial components of birdsong.”

However, the more I study phonetic transcriptions, the more I become convinced that they tend to be more informative than I thought. In fact, even though the people writing the transcriptions may be completely unaware of it, their choice of vowels almost always follows a consistent set of rules for indicating the pitch and inflection of the bird sound. Consonants are another story, but the consistency of the vowel rules is extraordinary once you learn to see it.

The first principle is this: different vowels represent different pitches in bird sounds. The following list arranges common (American) English vowels — plus the semivowels r, w, and y — from highest transcription pitch (at the top of the list) to lowest transcription pitch (at the bottom of the list).

- ee and y (as in feet and yes)

- ih (as in pit)

- eh (as in pet)

- ah (as in father)

- oh (as in pole)

- er and r (as in herd and rip)

- oo and w (as in boot and win)

The lowest-pitched bird sounds in North America are those of doves and owls — and it’s common knowledge that they coo and hoot, respectively. Meanwhile, if I tell you to listen for a “seet” or a “peep,” you’ll expect something high-pitched. Only medium-pitched sounds get filled in with other vowels, like the nasal notes from this Cooper’s Hawk, which Sibley’s guide describes as “pek-pek” notes and the old Audubon Society guides transliterate as “cack-cack-cack” (using vowels from the middle of the chart):

But what we’ve just seen isn’t the cool part. The cool part is how people use diphthongs — that is, vowel combinations — to consistently, systematically represent changes in the pitch of bird sounds. The correspondence between vowels and bird sounds isn’t random — it’s based on the acoustic properties of the human voice and the way it produces vowels and semivowels. The rules are simple:

- Monotone sounds are transliterated by single vowels, never diphthongs: for example, “tseet,” “peep,” “hoo.”

- Upslurred sounds are transliterated by two consecutive vowels, the first one lower on the chart, the second one higher. For example: w + ee = “whee.”

- Downslurred sounds are transliterated by two consecutive vowels, the second one lower on the chart than the first. For example: ee + r = “eer.”

- Overslurred sounds are transliterated by three consecutive vowels, the middle one highest on the chart. For example: w + ee + oo = “wheeoo.”

- Underslurred sounds are transliterated by three consecutive vowels, the middle one lowest on the chart. For example: ee + oo + ee = “eeyoowee.”

Believe it or not, despite the huge variety of ways to transcribe bird sounds, most transcriptions follow these principles — and for good reason, as we shall see.

Upslurred sounds

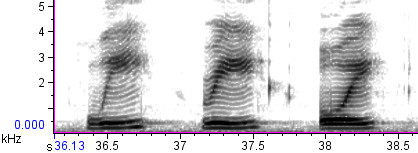

The commonest call of the Great Crested Flycatcher is a classic upslur, and like all upslurred sounds, it rises on the spectrogram from lower left to upper right:

The Sibley, National Geographic, and Audubon field guides all transliterate this sound as “wheep,” which starts with an “oo” sound (w) and changes to an “ee” sound — thus, spanning the entire range of the pitch table from bottom to top. This oo + ee combination virtually always denotes an upslurred sound, as it does in the “whit” calls of Empidonax flycatchers, the “squeet” call of Sprague’s Pipit, and the “kwit” flight call of Type 4 Red Crossbill. A look at the human voice on the spectrogram shows the reason:

Whenever the human voice pronounces a diphthong that begins low on the chart and ends high, the resulting spectrogram shows a distinct dark band that runs from lower left to upper right — in other words, an upslur. However, this dark band does not represent the pitch of the person’s voice — note that the darkness moves independently of the harmonics (the underlying horizontal lines), which change with the voice’s pitch. The dark bands are called formants, and they differentiate vowel sounds. (For a detailed explanation of spectrograms as they relate to the human voice, see this page.)

Downslurred sounds

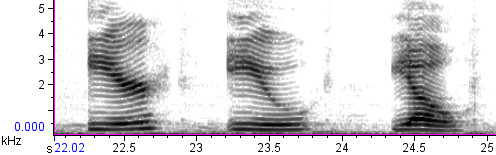

Like all downslurred sounds, the call of the Olive Warbler traces from upper left to lower right on the spectrogram:

Sibley transliterates this “teew” or “tewp,” National Geographic “phew,” and Audubon “kew.” In all cases, the vowel combination is ee + oo = “ew,” as it is in Sibley’s transcriptions of the American Robin’s “tseeew” alarm call and the “kewp” flight call of Type 2 Red Crossbill. Another classic vowel combination for downslurred sounds is ee + r = “eer,” like in the “pdeeer” call of Say’s Phoebe, the “veer” call of Veery, and the “cheer” call of Carolina Wren. As you might expect, spectrograms of the human voice saying “eer,” “eew,” and “yo” show downward-sweeping formants:

Overslurred sounds

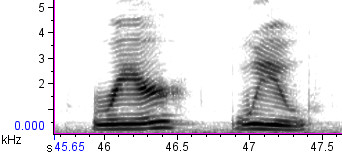

The burry overslurred call of the Couch’s Kingbird can be seen three times on the spectrogram below, mixed with shorter calls:

Sibley transliterates this as “kweeeerz” and Audubon as “queer” — in both cases, the vowel combination is oo + ee + er = “weer.” National Geographic goes almost the same route, with er + ee + er = “breeeer.” Similar patterns occur in Sibley’s “hweeeeeew” for Dusky-capped Flycatcher and “urrREEErrr” of Common Pauraque. And, of course, a similar pattern can be seen in spectrograms of the human voice pronouncing these combinations:

The possibility of standardization

So far, I have merely tried to describe the way people do describe bird sounds, not the way that they should do it. However, it may be possible to go one step further and create a standardized system by which transcriptions could communicate the basic properties of a sound to any audience unambiguously, and two people hearing the same sound would transcribe it the same way. Much more work would need to be done, particularly on consonants, but it might be well worth doing. I expect to explore some of the possibilities in future posts.

9 thoughts on “The Vowels of Birds”

Hi, Nathan. I enjoy your blog. This topic is interesting to me because I find almost all descriptions of sounds in field guides to be summarily useless. In my case, a recording is worth a million words.

But despite finding phonetic transcriptions of sound in field guides to be useless, I get immense value out of creating my own. You can describe a Yellow Warbler sound as “sweet, sweet, sweet, sweeter than sweet” to me all you want, but the only transcription that works for me is “ding, ding, ding, duh-duh-duh-dit”. I can remember that one and it sounds mostly like a Yellow Warbler to me.

I agree that some standardization would be nice. In the case of consonants, why should some use the “f” in a transliteration versus “ph”. Sometimes more consonants seem to indicate how pronounced or long the sound seems to the author and other times they just seem to be used to make a transliteration look more familiar or alien according to the whims of the author.

Anyway, I’ve meant to post a comment along the lines of your last paragraph before. It will be interesting to see more comparisons of human transliteration recordings versus actual bird recordings in the future and to see which ones are “right”.

Thanks for the blog.

Thanks for such an interesting and thought-provoking post! At the very least this is immensely helpful for interpreting bird sound descriptions in field guides. And the potential of standardization is exciting!

Great post. I like comparing differences among transliterations, and then noting how even when quite different on the page, different versions can still speak to the sounds of a species. Another approach I marvel at is F. Schuyler Mathews, who put bird songs to music. Poetic to be sure.

Excellent post, as usual. What this suggests, and which is something I’ve never considered before, is that we could try to make sound searching based phonetic descriptions on xeno-canto. If people use the same combinations of vowels, we could get over the usual hurdle of precise string matching (I search ‘coo-coo’ but someone else described my call is ‘doo-doo’) and use only the description category someone has described or is search for. Fascinating! Anyone out here who’d want to help us coding this?

Interesting, Bob, but I’m not quite sure what you mean — how would one search a description category? How would one enter such information when uploading files?

One would just enter a description of the sound one searches. The script then interprets this, comes up with the category of sound the description belongs to and tries to find matches within that category. So we would have a limited set of categories (as you outlined above), map each recording to a category, and use these to match user input to. The user doesn’t see anything of these categories of course. That’s all under the hood. For uploading, the recordist would try to describe the sound as one reads it in a field guide. Much work, I admit! Perhaps an alternative would be to build a set of descriptions per species. We still have the Birds of Peru descriptions by Dan Lane, for instance, which he generously gave us but we never used so far. That would be a start.

That sounds like an excellent idea. A complex task, though, to parse the vowel patterns. I guess you could start by assigning number values to the different vowel sounds, and then mapping certain combinations of letters onto those sounds. However, both the map and the numerical values of the vowel sounds will likely need to differ depending on the native language of the speaker.

By the way, there are certain tendencies when it comes to consonants as well, although few are as clear-cut as the vowel rules. I hope to investigate some in future posts.

Thanks Nathan! Nice presentation and fascinating topic. (My favorite has always been: “If I could catch one I would squeeze one and I would squeeze until it SQUIRTS!”! Anyone remember what that was, from an old National Geo tape.) But don’t the voice-recognition programs have a more precise and accurate ability to discriminate, or at least the potential to? Seems like it is a more direct approach as well. I would guess that by the time we worked out the vowel and syllabic approach, the sound programs would be where we want them.

More power to the voice recognition programs, Doug. But it seems like there would always be utility in standardized vocal descriptions as well — for use in new field guides, for instance, or to name sounds more accurately and reproducibly in the scientific literature. In addition, the understanding that most authors tend to follow the same vowel rules might help us better match historical transliterations of bird sound to modern recordings, connecting our current knowledge more accurately with the vast library of behavioral observations from naturalists of earlier generations.

By the way, that “squeeze it till it squirts” phrase is a classic and beloved mnemonic device for the song of the eastern Warbling Vireo. 🙂

Comments are closed.