Learning Laplands

In wintertime, huge numbers of Lapland Longspurs come down to the northern United States from their Arctic breeding grounds — sometimes gathering in enormous single-species flocks, but often mixing with other longspurs, Horned Larks, and Snow Buntings. At a distance, their cryptic winter plumage pattern can make them hard to pick out from these other birds. That’s why many people “look” for longspurs with their ears.

Away from the Great Plains, Lapland is usually the only expected longspur species, and one can usually detect and identify it by its characteristic rattle call, which generally resembles the rattles of other longspurs. Although the number of notes is highly variable, this call is pretty much the same across the Lapland Longspur’s entire (worldwide) range:

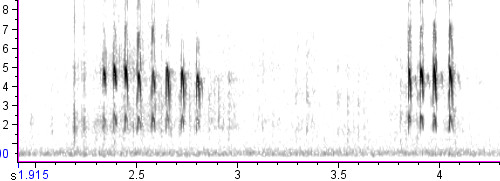

But this isn’t all that longspurs say. They give a variety of other calls, some of which are more immediately distinctive than the rattle. Here in Colorado, I recorded a longspur giving “chewlup” and “terlee” calls in addition to rattles:

As I started listening to recordings of Lapland Longspurs from other parts of North America, I started to hear other types of calls. Individual birds give at least 5 or 6 different whistled calls, especially on the breeding grounds, and individual repertoires seem to differ, especially from one geographic region to the next. In trying to catalog Lapland Longspur calls, I ended up making a map of variation. First, I found recordings from seven distinct locations where this species breeds in the North American Arctic:

- Seward Peninsula, western Alaska (LNS 49598 and LNS 141100)

- Denali National Park, central Alaska (LNS 50024)

- Colville River Delta, northern Alaska (LNS 131257)

- Babbage River, northern Yukon (LNS 61441)

- Bathurst Island, Nunavut (LNS 137341)

- Devon Island, Nunavut (LNS 61444)

- Baffin Island, Nunavut (LNS 61426)

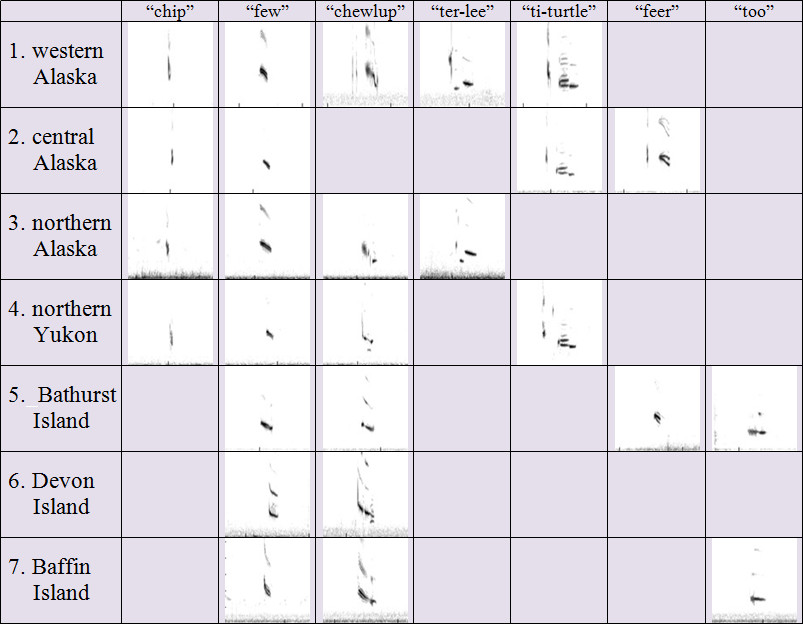

Then I went through the recordings and made a table showing the geographic similarities and differences in calls:

In the table above, all the spectrograms in a given row represent different calls from the same individual bird (except for the first row — the “chewlup” and “ter-lee” are from a different bird than the other three). Here are the takeaway lessons:

- Some calls are clearly the same across wide portions of the range. For example, the call that sounds like “ti-turtle” is clearly the same in western Alaska, northern Alaska, and the northern Yukon. But it does not appear in recordings from other regions — at least not in a recognizable form.

- This graph isn’t wide enough to show all the types of calls. In particular, the recordings from northern Alaska (#3) and Bathhurst Island (#6) contain multiple call types that I didn’t include because they didn’t seem to fit into any of the existing columns.

- Few, if any, of the whistled calls are truly universal. The only whistled call type that comes close to appearing in all regions is the “few,” and even then I’m not certain that the “fews” I illustrate above for Devon and Baffin Islands are really equivalent to the “fews” from elsewhere. It’s possible that more recordings would change this, but note that the extensive recordings from northern Alaska and Bathurst Island show an almost complete lack of shared calls — and that includes the ones I left out for lack of space.

- Most, if not all, of the calls can be heard in winter as well as summer. Though rather few recordings are available from wintering birds, it appears that the calls of longspurs wintering in western North America and on the Great Plains tend to resemble the those from Alaska (locations 1-3), while the calls of longspurs wintering in eastern North America tend to resemble those from Arctic Canada (locations 5-7).

What can we conclude from this information? Well, for starters, it’s pretty clear that these calls are learned, not innate. That would explain why birds from a given region tend to share call types, while birds from far away tend to sound quite different. It fits a pattern of regional dialects that are typical of learned vocalizations. Each bird learns not just one call typical of its region, but an entire set of regional calls — much like the Red-winged Blackbirds I discussed a while back. In longspurs, like in Red-winged Blackbirds, dissimilar calls likely fulfill similar functions in different regions of the Arctic. For example, longspurs expressing agitation at a human near a nest tend to cycle through 3-4 different call types — but the birds on Bathurst cycle through a totally different set of calls than the birds on the north slope of Alaska.

Obviously, people attempting to identify Lapland Longspurs by their calls in winter have their work cut out for them. My general impression is that longspurs wintering in Colorado sound the same year after year, consistently giving “few,” “chewlup” and “ter-lee” calls like the northern Alaska birds above. But if I went to, say, Iowa, the longspurs would be likely to sound rather different.

Much remains to be learned about the Lapland Longspur’s complex communication system. I’m looking forward to knowing more.