The Swifts of Mexiquillo

We were excited to arrive at Parque Natural Mexiquillo before the break of dawn in June. This underappreciated park is right on one of Mexico’s most celebrated birding routes, the Durango Highway — but it is an hour or two farther east than the Tufted Jay Preserve, and much less frequently visited. The drier forests of Mexiquillo host a noticeably different avifauna than the wetter areas closer to the coast. Mexiquillo is more likely to produce birds typical of the dry “sky islands” of southern Arizona: Buff-breasted Flycatcher, Western Bluebird, Plumbeous Vireo, and even American Robin. It’s much better habitat for the likes of “Type 6” Red Crossbills (which we recorded) and Eared Quetzals (which we did not find). Of course, it also has Red Warblers, Elegant Euphonias, and Rufous-capped Brush-Finches.

And it has a waterfall.

This is particularly noteworthy because the mountains of west Mexico are high and dry — and not much water means not many waterfalls. Which means not many places to look for waterfall-loving swifts.

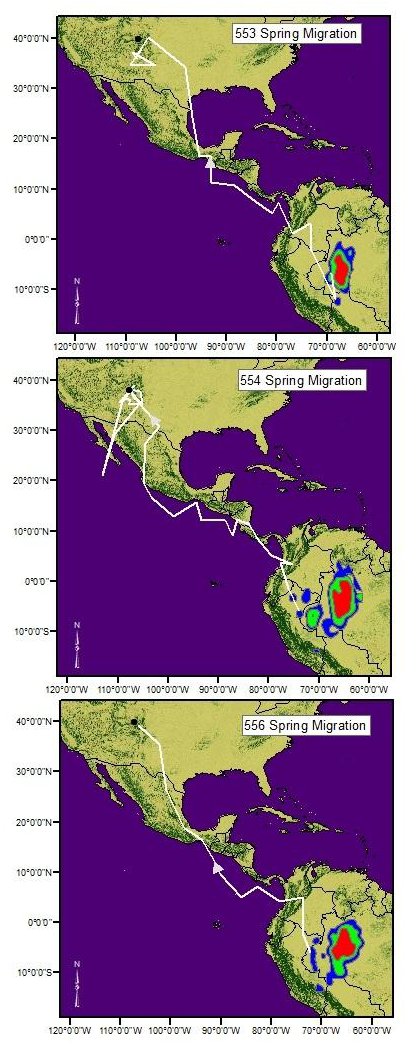

We were very interested to see what kinds of swifts would be flying around the waterfall at daybreak. A report from 2013 had us wondering whether this would be a good place to record Black Swifts, and a tantalizing recording from Chihuahua had us wondering whether something super-rare might be lurking under the cascada (and under the radar), like the “avian unicorn” White-fronted Swift (Cypseloides storeri).

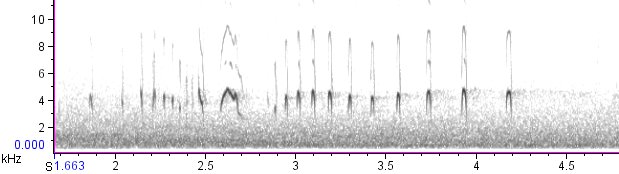

When we first arrived, before first light, all was quiet, except for the roaring water and the aerial singing of Violet-green Swallows. Off in the distance, a Spotted Owl hooted. No swifts. Soon a dawn-singing Pine Flycatcher became a serious distraction. By the time the sun was fully up, we were totally engaged in all the other wonderful birds in the park, and we had completely given up on the swifts. Until suddenly, something dark swooped by overhead with a sound like the crackling of electrical wires. Chestnut-collared Swift!

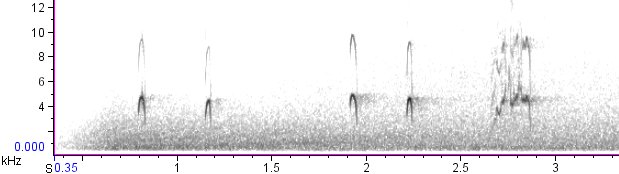

Then another group of swifts flew by, and I heard a sound familiar from the mountains of Colorado: Black Swift.

For the next hour, these two species swirled over our heads, sometimes swinging pretty low. The encounter was simultaneously a letdown and a thrill. On the one hand, it woke us up from the pipe dream of documenting some ultra-rare Cypseloides vocalizations. On the other hand, it was a terrific opportunity to spend time with two species that it can be awfully hard to see and hear well. It cleared up a long-standing mystery about whether the Black Swifts of Mexico might sound different from the ones farther north (answer: they don’t). And it gave us the field experience necessary to help identify the Chihuahua mystery swift as the first Chestnut-collared documented in that state. One key takeaway: Black and Chestnut-collared Swifts can look astonishingly similar, even when you get good, prolonged looks. But by sound, they can be separated right away.

While I concentrated more on the audio recording, Andrew was able to get some decent flight shots of the Black Swifts:

We were hoping to figure out whether the Black Swifts of Mexiquillo belonged to the northern subspecies niger, which breeds in the United States and Canada, or the southern subspecies costaricensis, which breeds in — you guessed it — Costa Rica. The birds in Mexico have been attributed to each of these subspecies by different authors. The Mexiquillo Black Swifts were surprisingly well marked, some with bright white foreheads, some with extensive white scalloping below. So we thought this might be a mark for costaricensis. But when Andrew reviewed and photographed Black Swift specimens in the Harvard collection earlier this week, he found it nearly impossible to separate the subspecies by coloration. The size difference is noticeable on the specimen table, but is subtle enough that it would be virtually useless in the field.

So, the subspecies of the Durango birds remains a bit of a mystery. Any comments or discussion would be appreciated!