Black Swift Wintering Grounds Discovered

This bird is always late to the party.

It was one of the last North American bird species to be described to science, in 1857. Its nest was not found until 1901. The first audio recording of its voice was not made until 1993. And every summer, across most of its breeding range, it is the last species to arrive from the south, often not appearing until the end of June.

But most remarkably of all, it was the only North American migratory bird to enter the 21st century with the location of its wintering grounds still a complete mystery.

By any measure, Black Swifts are bizarre. They nest in the spray zone of waterfalls, sometimes behind the water, so that juveniles may never have dry feathers between hatching and fledging. They take to the air before dawn, spend the entire day foraging for flying insects at altitudes so high that they often cannot be seen with the naked eye, and frequently do not return to the nest until after dark. Then they get up several times during the course of the night to regurgitate insects for their only child, who sat hungry and wet at home all day.

The high-flying habits of Black Swifts make them almost impossible to track during migration. The parents stay at the nest until the chick is old enough to fly in August or September, and then they vanish, not to be seen again until the following May or June. A few anecdotal observations and a couple of specimens have suggested that Black Swifts may migrate south along the California coast, and that at least some reach Costa Rica or Colombia in migration. But no observations, specimens, or band recoveries have ever revealed where the bulk of the population spends the winter. The species is not large enough to carry satellite radio trackers or transmitters, so the mystery has seemed destined to persist, barring a major advance in technology.

But in 2009, a group of researchers from Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory caught four Black Swifts in Colorado and fitted them with geolocators. Geolocators are not radio transmitters or satellite recievers, but rather primitive devices — just a light sensor, a digital clock, and a tiny memory chip. All they do is record the time of sunrise and sunset each day. But that’s all the information one needs to reveal where the bird has been. The time of local sunrise, measured against GMT, allows you to estimate your longitude — that is, what time zone you’re in. The length of the day, combined with the calendar date, tells you your latitude — that is, how far north or south of the equator you are.

There’s just one problem — since the geolocators can only record data, not transmit it, the only way to find out from the device where it’s been is to recapture the exact same bird a year after you saddle it with the tiny light-sensing backpack.

Knowing that Black Swifts have a very high fidelity to their nesting sites, the RMBO team hung mist nets at the two places where they had outfitted birds with geolocators the year before. It took three different trips over the course of the summer, but they managed to recover three out of the four geolocators — a remarkable 75% success rate. Today they announced the results: those three Black Swifts carried their little backpacks all the way to South America and back — specifically to the Amazon basin of western Brazil.

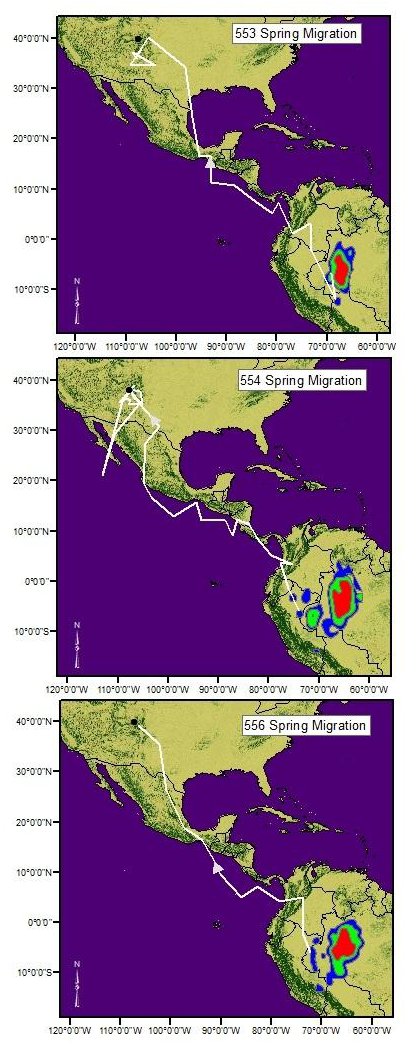

At right are the maps from the article published today in the Wilson Journal of Ornithology by Jason Beason, Carolyn Gunn, Kim Potter, Robert Sparks, and James Fox. The white lines on the three maps are the northbound spring migration routes of the three swifts whose geolocators were recovered in 2010. Fall migration routes, unfortunately, could not be accurately mapped, because the period of fall migration too closely coincided with the autumnal equinox, when day length is equal at all latitudes, making it difficult to measure north-south movement accurately.

The colored blotches in the western Amazon are the areas where the swifts likely spent most of the winter. They’re blotchy because the geolocators aren’t terrifically accurate, and also because the swifts apparently moved around a fair amount during the winter. It’s possible that they roosted in caves or cliffs for the night and then roamed extensively during the day, but the researchers raise the tantalizing possibility that wintering Black Swifts may actually stay aloft 24 hours a day, based on the behavior of the related Common Swift of Eurasia, which may be on the wing for up to 9 months of the year — or even several consecutive years, in the case of non-breeding individuals!

The authors stress, however, that no conclusions about roosting behavior can be drawn from the current study. If the wintering birds do roost in dark crevices like they do in summer, they could skew the geolocator data, which is based on light levels. Extensive cloud cover could also be an issue. There’s evidence of at least some errors in the migration tracks at right: the researchers stress that bird 554 did not, in fact, probably take a quick jaunt to the Pacific Ocean off of Baja California after arriving in Colorado — that data point is likely due to some type of irregular shading event that messed up the geolocator data. Nevertheless, the generally strong agreement between the tracks of the three birds provide a reasonable level of confidence about the quality of the data.

The Black Swifts were estimated to cover between 210 and 240 miles per day, on average, during their southbound and northbound migrations. More study needs to be done to determine whether their migration routes and wintering areas are typical of Black Swifts, or whether they are specific to the Colorado population.

For more information on the remarkable Black Swift, check out the book The Coolest Bird by late, great Colorado swift researcher Rich Levad, published online by the American Birding Association.

Literature Cited

Beason, J.P., C. Gunn, K.M. Potter, R.A. Sparks, and J.W. Fox. 2012. The Northern Black Swift: Migration Path and Wintering Area Revealed. Wilson Journal of Ornithology 124:1-8.

7 thoughts on “Black Swift Wintering Grounds Discovered”

This is incredible! I had no idea of any of this! What a remarkable bird! Even my husband, who is a non-birder, was impressed when I read this to him!

This story made the front page of the Denver Post today — pretty impressive!

Incredible! A great bit of felicity. It’s almost a shame the mystery is gone, but still it’s pretty cool!

Hey Little Swift – thanks for hauling that backpack around. Learning where you spent the winter, how fast you fly, your site fidelity are amazing secrets to uncover. But you are no less magical and breathtaking. The essence of your mystery defies human understanding – but we try.

This is wonderful information. I have been watching Black Swifts on nest in Northern Idaho for about 5 or 6 years now. I usually drive the 330 mile round trip in July and count the number of Adults on nest then go back the last week of August or early September and see how many chicks are getting ready to Fledge! I have some of my trips documented on my flickr photo site at: http://www.flickr.com/photos/terryandchristine/sets/740314/

Great information!!!

My first thought was, “Bloody brilliant detective work”. That’s pretty much my second thought too.

Comments are closed.