White-breasted Nuthatch, Part One

Birders have known for a number of years now that White-breasted Nuthatches sort out into three distinct vocal groups in North America — Pacific, Rocky Mountain, and Eastern — following a pattern of three-way separation that mirrors those of several other bird species, including the Solitary Vireo complex (split into Cassin’s, Plumbeous, and Blue-headed) and the sapsuckers (split into Red-breasted, Red-naped, and Yellow-bellied).

However, with the exception of field guides, the ornithological literature has been silent on this point. Nobody has done a systematic study on the marked regional variation in vocalizations of the White-breasted Nuthatch. The only in-depth study on vocalizations in the species was done by Gary Ritchison in Minnesota, and so the vocalizations of the Eastern form have been the only ones described in the literature for years; they were the only ones available on commercial bird sound recordings for years too. Even though the Birds of North America account was revised by its authors in 2008, they made no mention of vocal variation, which seems a shocking oversight. Spellman & Klicka (2007) published a molecular phylogeny of the species and found evidence for four distinct clades in the species, with boundaries exactly matching those of the vocal groups (except that they found the Rocky Mountain group was divided into two clades, apparently with identical vocalizations).

Thus, since I can’t find this information anywhere else, starting with this post, I’m going to start exploring these vocal differences in some depth.

“Quank,” etc.

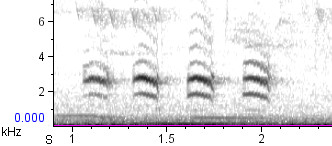

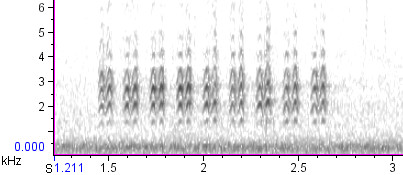

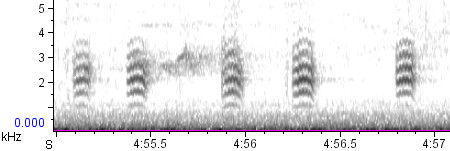

Here are the most common calls of the three nuthatch groups. For simplicity’s sake, we’ll always travel left to right across the country, so you’ll always see Pacific, Rocky Mountain, and Eastern birds in that order.

The first thing you’ll notice is that the Pacific and Eastern birds sound much more similar to one another than they do to the Rocky Mountain birds. Thus begins a theme we will see repeated many times. Spellman & Klicka found that the Pacific and Eastern birds were sister taxa, separated from one another by the less closely-related birds in the Mountain West. If this seems surprising, remember that the Solitary Vireo complex follows a similar pattern, with Cassin’s and Blue-headed Vireos looking and sounding more like each other than like Plumbeous.

The calls you see above are variable in each of the groups, so some of the differences you see between Pacific and Eastern in call length and overall inflection may not always apply. The most consistent difference seems to be one of pitch: the Pacific birds, with their more widely spaced partials, sound a lot higher-pitched than their huskier-voiced, more nasal Eastern cousins.

Identifying the Rocky Mountain birds, meanwhile, seems like a slam-dunk. Eastern and Pacific birds never make rapid-fire series of call notes, right? Well, actually, yes they do — several different kinds, in fact. I’ll be looking at those in my next post!

4 thoughts on “White-breasted Nuthatch, Part One”

Also, from your sonograms, it looks like the Pacific and Eastern fundamental (and harmonics) tone forms a single arch, whereas the Rocky Mountain birds have a double arch in each vocalization. Perhaps this is a topic for your future post(s).

I look forward to more, as the White-breasted Nuthatch is one of my favorite birds to watch and listen to (and they seem to like to hang around here all year in Central NM.)

You’re exactly right, Bill, and that double-arch in each note of the Rocky Mountain birds’ call is going to be key to identification once we introduce more types of calls from each group. Good eye.

Great post, I wasn’t aware of these regional variations. I’m looking forward to the next post! The Birds of North America account does briefly mention vocal variation but its buried in the systematics article.

Ah, right you are, Todd. Still, not mentioning vocal variation in the “Sounds” article seems sloppy to me. Thanks for the comment!

Comments are closed.