Sage Sparrow Subspecies

Guest post today by Walter Szeliga, who is starting to turn his audio recorder on some very interesting problems of identification and taxonomy.

Introduction

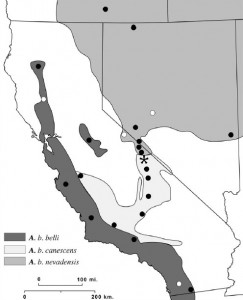

The specific status of the Sage Sparrow in North America has been in question since the publication of Ridgway’s 1887 treatise A Manual of North American Birds. In that volume, he attaches a footnote to the entry for Amphispiza belli nevadensis (p. 427): “With scarcely any doubt a distinct species”. Further subspecific division of the Sage Sparrow occurred in 1905 with Grinnell’s publication of “The California Sage Sparrow,” in which he described a third subspecies, “Intermediate Bell Sparrow,” A. b. canescens (Latin for “turning gray”). In addition to these three subspecies, a fourth, A. b. clementeae (“San Clemente Sage Sparrow”) is endemic to San Clemente Island — which, as a live firing range for the Navy, is all but impossible for most people to visit.

Recently, modern techniques, such as genetic sequencing (Cicero and Johnson 2007), have suggested that Ridgway’s feeling may be correct. Furthermore, a recent article in Zootaxa (Klicka and Banks, 2011) essentially constitutes a formal proposal to elevate A. b. belli and A. b. nevadensis to species status, complete with a new generic name, Artemesiospiza.

However, whether A. b. canescens should be recognized as a species distinct from A. b. belli remains in question. For now, Klicka and Banks (2011) lump it in with A. b. belli. Were the Sage Sparrows to be split, more birders would surely wish to identify these different groups in the field.

But identifying these groups in the field is tricky. During the breeding season, there are only a few regions of the American West where Sage Sparrow subspecies come in contact — a small area near Bishop, California, where canescens meets nevadensis; and a thin strip of the eastern California Coast Range from near Parkfield southward to the Little San Bernardino Mountains, along which belli meets canescens. In this area belli and canescens prefer quite distinct habitats, canescens breeding in the saltbush (Atriplex sp.) found on the floor of the Mojave Desert and belli preferring mountain chaparral dominated by chamise (Adenostoma sp.).

While Sage Sparrows on breeding territories can largely be identified to subspecies by range and habitat, the situation is quite different during migration and winter. The nominate A. b. belli, “Bell’s Sparrow,” is primarily restricted to the Coast Ranges of California and Baja California and is mostly sedentary, but its territory is invaded each winter by members of both canescens and nevadensis. In fact, these “winter” invasions begin very early for some canescens, which disperse after breeding to higher elevations in the range of belli as early as June (see Cicero 2010).

Thus, vocal and visual differences are frequently required to separate the three mainland Sage Sparrows to subspecies. Fortunately, there are some plumage differences that could prove useful in the field.

Plumage differences

- A. b. belli lacks distinct streaking on the mantle, while A. b. nevadensis shows streaking on the mantle.

- A. b. belli has a distinct black malar stripe, while A. b. nevadensis shows a less prominent pale gray malar stripe.

- A. b. belli shows a greater contrast between the head and body, with a darker gray head contrasting with a brownish body, while nevadensis is paler overall, with less contrast.

- In the hand, nevadensis is a distinctly larger and longer-winged bird than belli, features consistent with the greater migratory distance of nevadensis. Unfortunately, size differences are all but useless under field conditions.

Notice that all of the field marks mentioned so far involve separating A. b. belli from A. b. nevadensis. In nearly all of the categories mentioned above, A. b. canescens show features intermediate between belli and nevadensis; hence Grinnell’s suggested common name of “Intermediate Sage Sparrow”. For good comparative photos of all three subspecies, check out Robert Royce’s photo galleries of belli, canescens, and nevadensis.

That brings us to vocalizations.

“Bell’s” Sage Sparrow (Amphispiza belli belli)

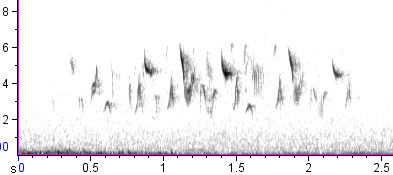

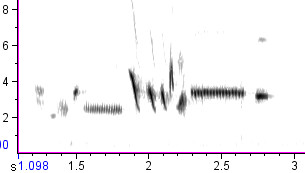

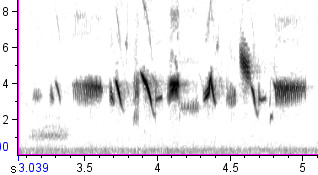

First, let’s look at a song from A. b. belli. A cursory glance at the spectrogram reveals a complex jumble of upslurred and downslurred notes on different pitches, for the most part lacking trills or buzzes of any significant length. As in other Sage Sparrows, songs from individual birds tend to be highly stereotyped, with most birds singing only one songtype and rarely giving shorter incomplete versions of this songtype.

“Interior” Sage Sparrow (Amphispiza [belli] nevadensis)

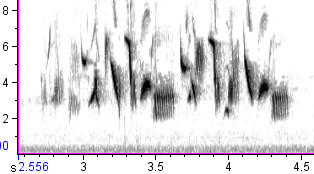

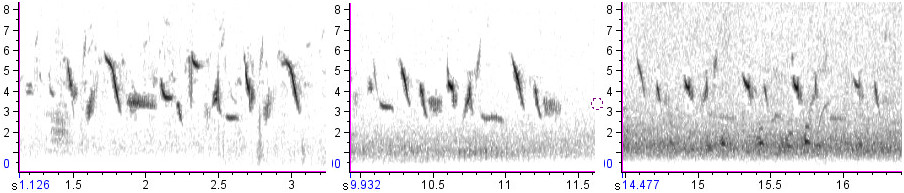

Moving on to A. b. nevadensis, we immediately notice a difference. The spectrograms show prominent trills or buzzy notes, most of which cover a fairly broad frequency range. The cadence of the song is different, the mix of quick short notes and longer buzzes giving it a stop-and-go, herky-jerky rhythm. Note the tendency for the ending to recapitulate the first part of the song, a tendency shared by many males in every subspecies group.

Here’s another nevadensis Sage Sparrow from Dolores County, Colorado:

And here’s a gallery of Xeno-Canto uploads of this subspecies:

A typical nevadensis song is fairly easily distinguished from classic examples of belli by its lower pitch, richer burry texture thanks to the trilled notes, and more syncopated rhythm. However, note that a few nevadensis songs, like Tayler Brooks’ recording at lower left, seem approach those of belli in these characteristics and might be difficult to identify in the field in the absence of other clues.

Interestingly, analysis of song length, and number of notes per song suggest that A. b. nevadensis has the longest song (~2.1 seconds, 8 notes per second), contrary to the suggestion in the Sibley Guide. In fairness though, individuals from A. b. belli do sing more notes per second (12 notes per second, ~1.4 seconds per song) than A. b. nevadensis. This does give the impression that they are singing a longer song.

“Intermediate” Sage Sparrow (Amphispiza [belli] canescens)

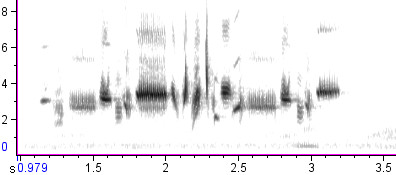

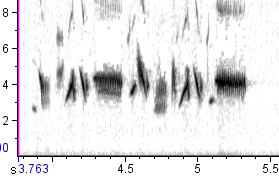

Not only is canescens intermediate between belli and nevadensis in range and appearance, it also appears confusingly intermediate in song. Some songs, like the three below, closely resemble those of belli:

Other recordings of canescens from farther north and east appear more similar to nevadensis song:

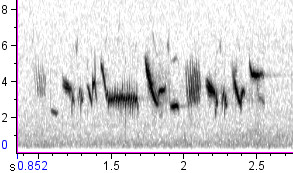

Here are a couple of recordings from within the breeding range of canescens in January and March, when migrant nevadensis can’t be ruled out:

Conclusion

While range, habitat and plumage may help identify many Sage Sparrow individuals to subspecies, there also appear to be useful differences in song. These song differences appear to be greatest between A. b. nevadensis and A. b. belli, with A. b. canescens forming a confusing intermediate group. It’s possible that song in canescens grades clinally from nevadensis-like songs in the northeastern part of its range to belli-like songs in the south and west. It’s equally possible that some of the nevadensis-like songs above actually belong to that subspecies instead of canescens.

On the whole, it seems that “classic” songs of nevadensis and belli are fairly easy to distinguish, but any Sage Sparrow singing an intermediate song may not be identifiable to subspecies by voice alone.