A Pygmy-Owl Challenge

The Northern Pygmy-Owl is a fascinating bird for those of us interested in vocalizations and taxonomy. Many people think that what we call “Northern Pygmy-Owl” may contain somewhere between two and four species, based on regional differences in vocalizations. Here’s a brief overview of the differences, according to The Sibley Guide to Birds (2000), with a typical spectrogram and sound of each:

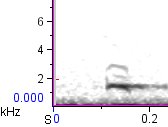

Pacific birds

According to Sibley, birds along the Pacific Coast of North America “give very slow single toots (1 note every 2 or more sec).” The example below is even slower than most; 2.5 seconds between notes seems pretty standard. Although one might expect birds in Montana to be part of the Interior West group, the sole recording available seems to fit better in this group.

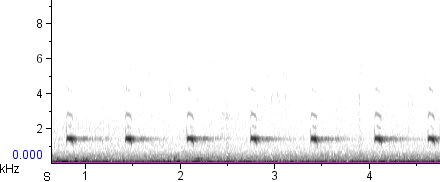

Interior West group

Very few recordings of this group are available online (or anywhere else) — just two or three from Colorado [1 2] and one from Utah. They all seem to give single notes at very regular intervals, just over 1 second apart, totalling about 50 “toots” per minute when they’re going full-bore.

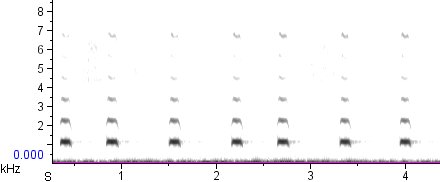

Mexican group (“Mountain” Pygmy-Owl)

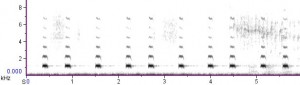

Sibley says these birds “give mainly paired notes more rapidly (about 1 pair every sec).” Paired and single notes are usually mixed together, as on the recording below, and the paired notes are only slightly closer together than the single ones:

However, “Mountain” Pygmy-Owls also sometimes forgo the paired notes in favor of a rapid-fire string of single hoots almost identical to the song of the Northern Saw-whet Owl:

What we don’t know

Nobody knows exactly where the changes between these songtypes occur, or how abrupt they are, because we just don’t have enough data. Most recordings of Northern Pygmy-Owl are of the highly vocal Mexican birds. As I mentioned above, very few recordings exist of the Interior West birds. There are none from potential areas of transition, like Idaho, Wyoming, northern Arizona, or New Mexico.

Now, my friend Arch McCallum is setting out to get to the bottom of this tricky situation — and you can help.

If you have access to Northern Pygmy-owls anywhere in their range this spring and summer, please do one of the following:

- Find a singing pygmy-owl.

- Get out a stopwatch and count how many “toots” the bird makes in one minute.

- Send this information, along with location, date, and time of day, in an email to Arch (mccalluma AT appliedbioacoustics.com) or post it in the comments below.

If you wish, you can also make a one-minute audio recording. (Just take a video with your digital camera, or get a cheap voice recorder if you don’t already have the means.) Actually, if you wish, you’re welcome to record (or listen to) the bird for longer than a minute! The more data, the better.

Hope to see a lot of data points roll in this spring! Here’s to good owling.