How Fast Is That Vireo Singing?

I can still remember the first time I heard a vireo “complex song”. It was after completing a transect for Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory in San Miguel county, Colorado, as I was walking through some pinyon-juniper forest, looking for things to record. I found a singing Plumbeous Vireo, and set up to record it singing. No sooner I had turned on the recorder, though, when it started belting out this crazy run-on jumbled song! I was taken completely by surprise, not even knowing Plumbeous Vireos had it in them to sing so awesomely.

Since that day I’ve heard complex song from many vireo species, but it’s still something I don’t hear very often, and a treat whenever I do. This type of vireo song is mentioned fairly extensively in BNA, often under different names. For Bell’s and Black-capped Vireo it’s called “courtship song”, and said to be given when the male is closely associated with the female bird. For other species, such as Plumbeous Vireo, it’s called “complex song”, and said to be given in a variety of circumstances. In my experience, though, it’s most often given by agitated birds, either after playback, or after an encounter with another member of their species. Occasionally a song that is either complex song, or possibly subsong, is heard from birds during fall migration as well.

Most vireo complex songs tend to follow a pattern, with song-like phrases mixed with high, squeaky notes. There appears to be some variability, with a higher agitation rate correlating to fewer song-like notes, more high-pitched notes, a faster pace, and sometimes a longer strophe length. The Solitary Vireo complex, Gray, Warbling, and Yellow-throated Vireos all fall into this broad pattern. Hutton’s Vireo also seems to belong in this group, though like its primary song, its complex song is also atypical.

Black-capped and Bell’s Vireos seem to give more discrete complex songs, called courtship song in BNA for both these species. In both species the complex song is reminiscent of their primary song, but quieter, faster, and more jumbled sounding, but without the long, continuous run-on character of the above group and without the incorporated high-pitched squeaky notes. White-eyed Vireo may also fall into this group, though it’s song seems to have more call-like elements and is more run-on.

A third group, made up on Red-eyed and Black-whiskered (and presumably Philadelphia) Vireos seems to rarely give a complex song at all. Indeed, BNA doesn’t mention such a vocalization for Philadelphia or Red-eyed Vireo, and only briefly for Black-whiskered. What I’ve heard from Red-eyed sounded more like the complex songs of the first group than the second, but in general seem less well differentiated from the primary song.

Below are examples of complex songs for every species for which I could find recordings. Needless to say, if any of you reading this have recordings of species not represented here, or more examples of any of these species, please let me know!

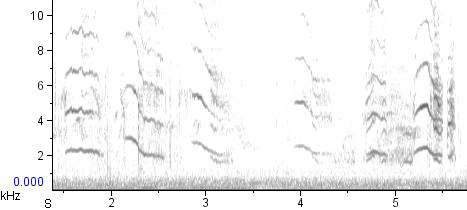

Plumbeous Vireo

Probably because I consider it the “default” vireo complex song I’m going to cover this species first. All of the vireos of the Solitary Vireo complex sing similar complex songs; typically these are fast, jumbled series of song-like notes, call-like notes, and high-pitched squeaky notes.

Blue-headed Vireo

The complex song of the eastern representative of the Solitary Vireo complex sounds similar to Plumbeous Vireo, and there are perhaps more recordings of complex song from this species than any other. In addition to the examples from xeno-canto below, the Macaulay Library has three cuts: ML#84774, 84775, and 100870.

Cassin’s VireoThe complex song of this species is like the above two in broad details. The only recording I was able to find was one at the Macaulay Library: ML#105665 |

Yellow-throated VireoThere is remarkably little information on the complex song of Yellow-throated Vireo. Macaulay has two cuts (ML#164094 and ML#73885) of sounds tending towards complex song, and it seems like it would fall into the same mold as the Solitary Vireo group. |

Gray Vireo

From the limited sample size of the complex song of this local western species it seems that it sings this vocalization with more distinct song-like notes, mixed with high-pitched squeaky notes, but without the harsh call-like notes of the Solitary Vireo complex. BNA says of this vocalization “most frequently heard on breeding grounds (central Arizona and w. Texas), but also heard on wintering grounds in Big Bend region, Texas (JCB) and Sonora, Mexico.”

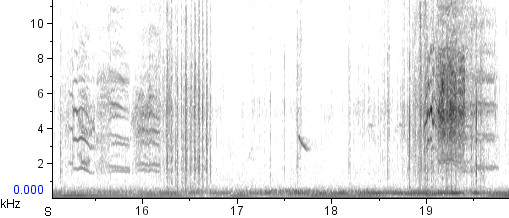

White-eyed VireoOf all the vireo species, the complex song of White-eyed Vireo is perhaps the most striking. It is a remarkable series of run-on calls, mixing song-like elements, call-like elements, and things in between. BNA calls this vocalization “rambling song”, and says “Rambling Song is produced by adult males in a variety of contexts and frequently by immature birds.” |

|

Warbling VireoAs if the song of this bird wasn’t complex enough already! The few times I’ve heard Warbling Vireo complex song it fell into the general mold of this vocalization type: song-like notes mixed with higher pitched squeaky notes. The examples I’ve heard don’t seem to mix in any call-like notes. BNA doesn’t even mention this song type for this species, and given the number of Warbling Vireos I’ve seen and heard and how rarely I’ve heard complex song from them I suspect this is a relatively rarely given vocalization. |

Hutton’s Vireo

A somewhat atypical species of Vireo by North American standards, the complex song of Hutton’s Vireo falls into the same category. Like the others above, however, it contains song-like elements and high-pitched squeaky notes. Overall, though, it is a slower song than the other vireo species, and differs less from the primary song in this regard. BNA makes no mention of complex song for Hutton’s Vireo.

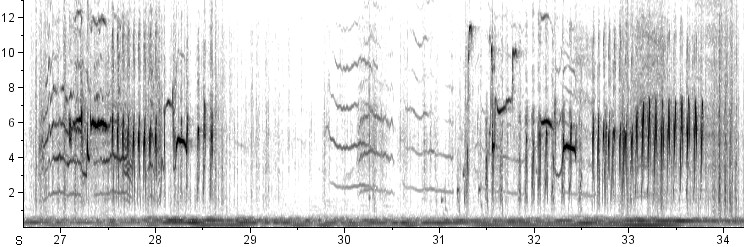

Bell’s VireoBNA calls the complex song of Bell’s Vireo “courtship song”, and says that it is given when the male is in close proximity to the female. That, coupled with the distinctive nature of this vocalization (it tends to come in more discrete phrases without either the high-pitched squeaky notes or call-like notes given in other vireo complex songs) suggests that it falls into another sub-group of vireo complex songs. |

|

Black-capped VireoBlack-capped Vireo complex song tends more towards that of Bell’s Vireo than that of other vireo species, but seems to contain more calls and fewer song-like elements. It almost sounds like a mix between Bell’s and White-eyed Vireo fast songs. Like in Bell’s Vireo, BNA calls this vocalization “courtship song” and says it is mostly given when the male is in close proximity to the female bird. |

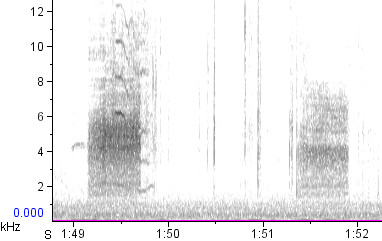

Red-eyed Vireo

The closest I can find to a recordings of the complex song for this species are linked below. I’ve heard other instances of complex song by Red-eyed Vireo that tend a bit more towards the Solitary Vireo type, but in general it seems that this species has more song-like notes in its complex song, few if any call-like notes, and fewer of the high-pitched squeaky notes. Given how common this bird is, and how many recordings of it are available, I believe that complex song is very rarely given by this species.