Murder Most Foul

Eleventh of May, 2009, just before 11 AM: I was walking down the road in upper Carr Canyon in the Huachuca Mountains of Arizona, hoping to find something interesting to record. A Dusky-capped Flycatcher was calling occasionally; some distant Yellow-eyed Juncos and Western Tanagers were singing; but the day was beginning to heat up, and bird activity was waning. Near where I parked my car, I heard some quiet high-pitched squeals, but they didn’t seem to belong to anything in particular. For a moment I got excited when a pair of Buff-breasted Flycatchers drove off a pair of Brown-headed Cowbirds that had been, I guessed, “casing the joint” — but this interaction was brief and quiet and I got none of it on tape; nor could I find the flycatchers’ nest.

A minute later, from back near my car, I noted that high-pitched squealing again. Belatedly, I realized it sounded like nestlings. Eager to record some begging calls, I headed for the sound, which was coming from near the top of a short oak, and turned on my microphone.

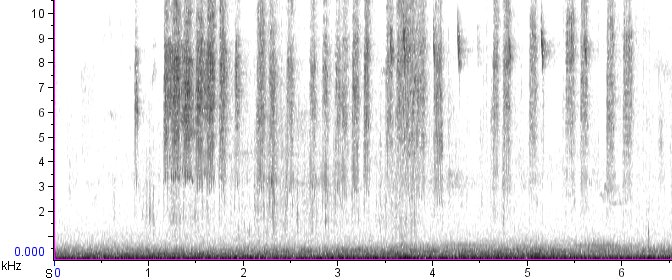

At first it just sounded like baby birds being fed:

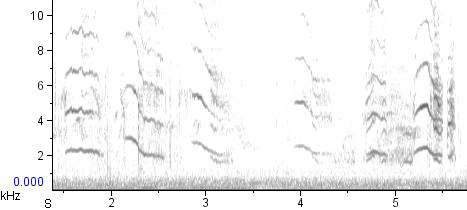

But soon it became clear that something else was going on. There was more activity in the tree than you’d expect from parents feeding nestlings — at least two or three birds were fluttering agitatedly in the crown, but I couldn’t see what kind they were, or what exactly they were doing. It started to sound less like begging calls and more like distress calls:

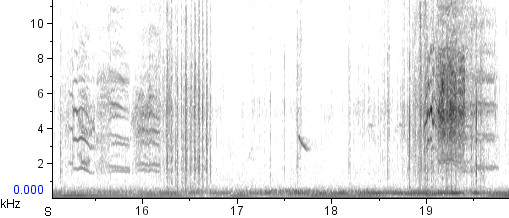

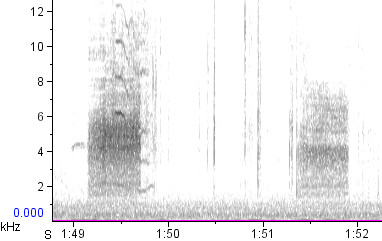

And then, suddenly, a large dark bird took off from the tree with something dangling from its bill. Behind it came a smaller bird in hot pursuit:

The birds landed in the open for a moment, long enough for me to see that the nest robber was a male Brown-headed Cowbird, and the frantic parent a Hutton’s Vireo. Then the cowbird took off with the nestling and the Hutton’s went after it, far out of my sight.

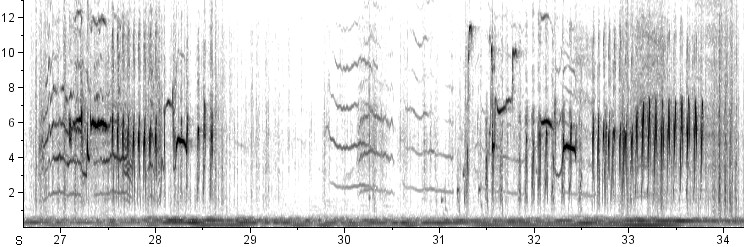

But the squealing at the nest continued. After a moment I risked walking towards it, and discovered the female cowbird pecking furiously at the contents of the nest, while another Hutton’s Vireo, or the same one, flitted around it and scolded it ineffectually:

Within a couple of minutes, the squeals stopped, and I could see the female cowbird eating something out of the nest. After another minute she fled the scene, leaving the adult vireo alone with the ruined nest, and me as a witness to a particularly brutal version of a very rare event.

It has long been known that Brown-headed Cowbirds will occasionally destroy the eggs of their host species instead of parasitizing the nest. It is rarer for cowbirds to attack nests after the eggs have hatched, but even so, the removal of nestlings by cowbirds has been documented one or two dozen times in the literature. In some of these cases, the cowbirds have been seen to eat the nestlings. However, the vast majority of all such attacks have involved solo females. In only two or three cases has nest predation involving male cowbirds ever been documented (see Igl 2003 and the references cited therein).

Why do cowbirds do this? One fascinating line of thinking is the “mafia hypothesis,” which holds that cowbirds come back frequently to check on the eggs they have laid in other species’ nests — and if they find the cowbird egg has gone missing (presumably because the host parents have recognized it as an imposter and ejected it), the cowbirds destroy the nest in retaliation (Hoover & Robinson 2007). By forcing the host parents to build a new nest, the cowbirds may be giving themselves another chance to parasitize it at a later date.

I can’t comment on the validity of the mafia hypothesis, but I can say that what I witnessed was fascinating, and a little disturbing — and yet another reason to follow up on odd, unidentified squeaks in the forest.