The Alternate Song of Prothonotary Warbler

They don’t call it the Golden Swamp Warbler anymore, but name would still be apt, because the flame-yellow Prothonotary is a familiar sight in the swampy areas of southeastern North America. It’s a wonderful and evocative bird, one that even non-birders tend to notice when it perches or sings nearby. It’s one of the few warblers that nests in cavities, and it is the sole member of the genus Protonotaria.

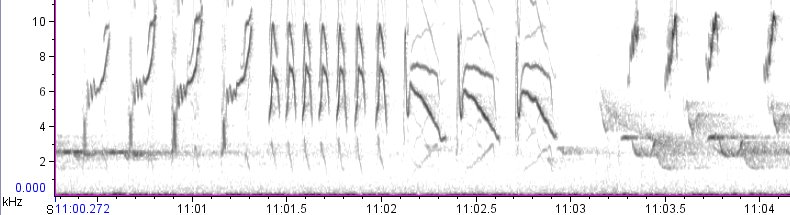

In 2006, I joined a volunteer team in Cornell’s search for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker in the White River National Wildlife Refuge of Arkansas. During the two weeks I spent walking around in the untrammeled, uncampephiled wilderness, I had many spectacular close-up encounters with wildlife, but the most amazing was with a male Prothonotary Warbler. I was standing in hardwoods on the edge of a flooded swamp when the golden bird popped up over the water and began to sing. I switched on my microphone to record it, and suddenly it flew into a leafless sapling right over my head. I didn’t dare breath or move; I just kept the microphone running, hoping the bird would stay in the tree, hoping it would sing again. Sure enough, after a few minutes of foraging it began to belt out its familiar primary song: a fast monotone series of high clear upslurred whistles, not particularly musical, often transcribed as “sweet sweet sweet sweet sweet.”

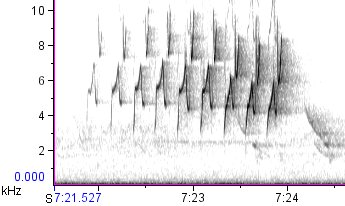

But then the bird did something even more extraordinary. It began to sing another song, one that was so faint that if the bird hadn’t been within five meters of me, I surely wouldn’t have heard it. And it was like nothing I’d ever heard from a Prothonotary before:

I went to the literature to find out what I had recorded, and discovered this in Lisa J. Petit’s Birds of North America account (emphasis mine):

Second, less frequent song is sung primarily during interactions with females, often in aerial Flight Display. This extended song (Spector 1992) is longer and slightly more complex than primary song, beginning rapidly and slowing down at end: chwee-chwee-chwee- chwee, teer, teer, teer (LJP) or che-wee-che-wee-chee-chee, chee-chee-che-wee-che-wee (Walkinshaw 1979). Brewster (1878) described this song as resembling song of Canary (Serinus canaria), sung quietly, and consisting of “trills or water-notes interspersed.” Roberts (1899) referred to the song as beginning with the “usual rapid monotone” and ending with a “varied warble.” No sonograms of this song are known to exist.

“No sonograms known to exist,” of course, is the same thing as saying “no recordings known to exist.” Well, we fixed that, didn’t we?

Or did we? Upon reflection, the quote above demonstrates some of the difficulties inherent in trying to match old voice descriptions with modern recordings. Is this really the “alternate” song of males? After all, no female was present, and the bird wasn’t singing in flight. Could it be some other type of song? In her account, Petit also mentions two other potential candidate vocalizations, apparent juvenile subsong and female song:

Two separate observations by LJP during Jul 1985 of immature birds (sexes unknown, both in femalelike plumage-one color-banded, 45 d old; the other unbanded, assumed immature on basis of behavioral interactions with adult pair) singing quiet, raspy, oriolelike warble that did not resemble primary song of adults. Songs were 2-3 s long and were repeated 3-4 times. In Jun 1987, an unbanded female (apparently adult, since it was building nest) was heard to give same type of song, repeated 3 times.

I’m not sure how female song fits into the picture, or whether some of the observers cited in the first quote might have been describing it, but one thing is clear: What I recorded was not subsong. Subsong is given by juvenile birds between fall and spring as they practice for their big debut on a breeding territory. It’s poorly structured, with individual notes randomly mixed and rarely repeated, or repeated in garbled form. The song I recorded, on the other hand, was crystallized: the bird repeated it more than a dozen times, and each time it followed the exact same syntax pattern, with small variations in the exact number of notes A, B, and C, but absolutely no variation in their order, fine structure, or rate of delivery.

Many warblers have complex alternate songs. Some better-known examples include the “flight songs” of Ovenbird and Common Yellowthroat (for the latter, listen here, between the 21 and 24 second marks). Paul Driver’s got a neat recording of the extended song of Worm-eating Warbler, and Andrew Spencer has posted to Xeno-Canto what may be an alternate song of Black-and-White Warbler, although it may also be a type of call. Many of these song types are rarely heard and even more rarely recorded, so I’d love to hear of more examples.

Given that Prothonotary Warbler has attracted a good deal of research attention over the years, I would be surprised if nobody else had recorded the alternate song by now. If you have any information to share, please let me know. It’s probably worth writing up a note for publication in a journal.