Mexico’s Mystery Owl

It’s not every day that you photograph and audio record a bird that has never been photographed or audio recorded before.

But that’s what we managed to do Thursday night, on the trails above Rancho La Noria in the state of Nayarit, Mexico. At the end of a madcap 12-day birding trip, we finally connected with our primary target, one of the most elusive birds in Mexico – Cinereous Owl (Strix sartorii, also known as Mexican Barred Owl).

Known from about 30 specimens taken between 1873 and 1948, this bird has eluded almost all detection for the past half century, and its taxonomic status has been a major mystery. Is it a subspecies of the Barred Owl of North America, as the American Ornithologists’ Union currently classifies it? Is it a species in its own right, as the International Ornithological Congress decided to call it following recommendations from a 2011 genetic study? Or is it a subspecies of the Fulvous Owl, as some have speculated following recent records of Fulvous Owl from within the supposed range of Cinereous [1 2 3 4 5]?

To answer these questions, good photos and (especially) audio recordings of Cinereous Owl were sorely needed. And here are the first ones.

The search

When we first began considering a trip to West Mexico with our friend Carlos Sanchez earlier this spring, the Cinereous Owl was a major motivator, and we planned a good portion of the trip around it. We contacted Steve N. G. Howell, the author of the field guide to Mexican birds, one of the only people to have encountered Cinereous Owl in the wild. He recommended the trails above Rancho La Noria (a.k.a. Cerro San Juan), where he had found the bird in the past, but had been unable to get audio recordings despite four trips specifically for that purpose. So we knew the bird wasn’t going to be easy.

Rather than head straight for Rancho La Noria, we started our search at Cerro La Bufa in Jalisco, on the recommendation that the habitat was very similar to that at Rancho La Noria, but more extensive, higher in quality, and easier to access by road. Nevertheless, in a night of owling that included playback of Fulvous, Barred, and Spotted Owls (on the assumption that Cinereous probably sounded enough like one of these to respond to a tape), we only managed to find Spotted Owl, Mottled Owl, and Whiskered Screech-Owl.

We tried again a few nights later on Volcan Nieve (a.k.a Nevado de Colima), the source of at least one of the specimens of Cinereous Owl. Again, no luck. However, in our limited time we were only able to survey a small portion of the habitat along one of several roads on the peak, so Cinereous Owl could easily be hiding up there somewhere.

We probably should have tried owling during our night at the Reserva Chara Pinta (Tufted Jay Preserve) near El Palmito, Sinaloa, but by that point in the trip we were too tired. So our last chance for the mythical bird came down to our final hours in Mexico, at the spot Steve Howell had originally recommended.

The find

Carlos opted for hard-earned sleep instead of an exhausting wild goose chase, so we headed up the Rancho La Noria trails at dusk without him. Our process was the same as at the other sites: stop, listen for a couple minutes, and then try speculative playback of all three Strix owls, to see if we could get some kind of response. At our third stop, we didn’t even get to the playback, because we heard the bird we were listening for singing spontaneously far up the trail! Just as Steve had described, it sounded a lot like Fulvous Owl, but slightly different.

Elated, we quickly moved up the trail to get closer to the still barely audible owl. After several more stops it became apparent that we weren’t going to be able to get closer to it on the trail, so we tried some playback. This did not succeed (at least initially) at bringing the singing bird closer, but we did start to hear what sounded like the wail call of a female Strix owl from the same area. So we bit the bullet and started bushwhacking down a steep slope. We didn’t make it far when the apparent male of our target pair called from right over our heads, twice! Quick reflexes and the wonders of pre-record buffering, and we had the first ever recording of Strix sartorii (at least the first good ones, after our far more distant cuts a few minutes before).

And that was it. After several minutes of silence we played back what we had just recorded, we played back Fulvous Owl, and we played back the female wail call of Spotted Owl – no response. But we were still hearing a consistent wail call in the distance, and we reasoned that we would stand a better chance of getting more audio if we tried to get closer to the source of that call. Two steep ridges later and we were far closer to the calling owl, and also on a trail that, had we but known of it, would have saved significant effort. A bit more walking, and we were soon staring right at the source of the wail call – not a female as we had assumed, but a begging fledgling Cinereous Owl (see the photo above).

We spent the next hour or so with the young bird, documenting what we could, but the adult birds never showed. So we decided to get a precious few hours of sleep and return before dawn, when we hoped the adults would vocalize more and possibly return to feed the juvenile.

A few hours later, this time with Carlos, we were standing on the same stretch of trail. It didn’t take us long to find the same shrieking fledgling, but there was no sign of its parents. As dawn approached and the adults never showed we got more and more nervous, but then finally the young one made a rather more urgent sounding call, flew off out of sight, and the sounds of a feeding event floated through the woods.

After two apparent feedings (both recorded; see above), an adult bird finally sang a hundred meters or so down the trail. Some quick repositioning, a few audio cuts later, and a bit of playback, and we were looking right at it – an adult Cinereous Owl! Over the next half-hour we obtained all the evidence we could have hoped for, audio and visual. A few other residents of the forest took some exception to the singing owl (including a White-throated Thrush and a Sharp-shinned Hawk), but in the end we had to tear ourselves away from it all. It was time to return to Guadalajara, and the US, tired but thrilled at our success.

The analysis

While seeing such a rare animal was an awesome experience, the real interest for us was to see how these birds compared to both Barred and Fulvous Owls, and try to figure out where Cinereous Owl actually belongs. All of the below is with the caveat that our sample size is small (just one adult, likely a male).

Vocals

Most Strix owls, including Barred and Spotted, have two song types, one with notes in a species-specific rhythm, and another with notes in fairly steady series. We recorded both song types from Cinereous.

At first glance, the rhythmic song of Cinereous Owl is far more like that of Fulvous Owl than the familiar “who cooks for you” of Barred Owl. In fact, it is so similar that some might argue it is evidence that Cinereous and Fulvous could be considered conspecific. But a closer look shows some differences. The song of Cinereous is significantly lower pitched than that of Fulvous (which is to be expected since Cinereous is a larger bird). And it consistently had two extra notes appended to the end, even when singing naturally before playback. (This Fulvous Owl in Chiapas gave one extra note at the end of its song in response to playback.) The note shape and pace also differed, with Fulvous having more disyllabic notes given slightly faster, imparting a different cadence to the whole song.

The difference in the series song may actually be more striking, because it’s possible that Fulvous Owl lacks this vocalization type altogether. We have not been able to find a single recording of the series call from Fulvous Owl, even in their pair duets or in response to playback, when other species are more likely to give them. Instead, excited Fulvous Owls seem to stick with the rhythmic song, often in duets, tossing in occasional “caterwauling” barks. Although it’s hard to prove a negative, it’s tempting to conclude that Fulvous Owl lacks a series song, given that good online recordings are available of over 15 different individuals/pairs calling, many in response to playback.

Since we weren’t able to find a recording of the series song from Fulvous Owl, we can only compare what we got from Cinereous with Barred Owl. Compared to the series song from Barred, what we recorded from Cinereous was similar in pitch, but quite different in pace and overall pattern. In Barred, the series song rises slightly but consistently at an even pace before ending in a slightly modulated, falling note. In our sample of Cinereous, the series song started and ended at a lower pitch, with a few higher pitched notes in the middle, and a more stuttered pace throughout.

Visuals

Plumage-wise, Cinereous Owl clearly looks more like Barred. It isn’t hard to see why they were lumped for so long, especially considering that the vocal differences were unknown. But that’s not to say they’re identical, and Cinereous Owl can be told from both Barred and Fulvous Owls with a good view.

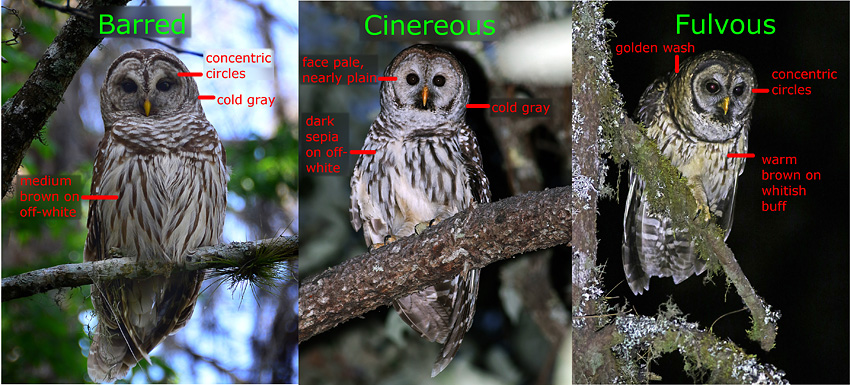

The first thing that immediately struck all three of us when we saw the adult Cinereous Owl was how pale its face was. Compared to both Barred and Fulvous Owls, the facial disk of Cinereous Owl is paler (without obvious darker concentric rings), and compared to Fulvous, grayer. Indeed, the overall colder gray coloration is a good way to distinguish Cinereous from Fulvous Owl. This is most obvious in the differences of the underparts pattern (dark sepia streaks on an off-white background for Cinereous vs. warm brown streaks on a light buffy background for Fulvous), and in the color of the collar (cold gray for Cinereous vs. golden brown for Fulvous). Compared to Barred, which is far more similar to Cinereous in these features, the main difference is that the streaks below on Cinereous are slightly darker, not a medium brown. See the photo below for a comparison of all three species (and click to see a larger version without the labels). Here also are a few more good photos of Fulvous Owl from Oaxaca [1 2 3 4] and from farther south [1 2 3 4 5].

A final, if far more subtle visual clue, deals with the feathering on the toes. In both Barred and Cinereous Owls, the feathers extend all the way down the toe to the base of the claw. In Fulvous, the toes are partly bare of feathering. This can be difficult to discern in the field, but with good photographs it can be a useful feature (and it is visible in the large version of the comparison photo, which you can see by clicking on the photo above).

Conclusions and Questions

1) While our sample size is limited, what we were able to audio record clearly supports considering Cinereous Owl separate from Barred Owl. Vocally, the two are not even close. Add that to the genetics in the 2011 paper, and there’s no reason to continue considering sartorii a subspecies of Barred Owl. (This is also why we support the name “Cinereous Owl” instead of “Mexican Barred Owl”).

2) Is sartorii perhaps a subspecies of Fulvous Owl? This situation is a bit more murky. Vocally, the two are close, at least in the rhythmic song. But with subtle differences in that song, and more marked differences in plumage and size, we think the case can be made that both be considered separate. If it can be determined definitively that Fulvous Owls lack a series-type song, that would be a strong argument in favor of separate species status for Cinereous.

3) Several people have wondered whether the apparent Fulvous Owls recently found in Oaxaca are really Fulvous Owls. We think our photos (in conjunction with the photos of Fulvous Owl linked above, and the many available audio recordings) demonstrate that the Oaxaca birds can be definitively identified as Fulvous Owls, and ruled out as Cinereous. But putting this question to rest raises a host of others. How far north and west are Fulvous Owls found? Do they currently overlap with Cinereous Owls in Oaxaca (which has specimen records for both)? Is one population expanding? Are the two interbreeding? Do intergrades exist?

What is needed now are more recordings and photos, especially from the other parts of Cinereous Owl’s range, in Guerrero and (even more importantly) Veracruz and Oaxaca. Hopefully the recordings we were able to obtain from Nayarit will help anyone out there trying!

Further reading

For more information on Cinereous and Fulvous Owls, check out the detailed bibliography at the end of Michael Retter’s blog post from 2012. At this writing, most of the links are broken if you try to click on them, but will work if you copy and paste the URLs into your browser.