A Dove Detective Story

I love an auditory mystery.

For many people, an avian auditory mystery is a “whodunit” — a quest to find out what species of bird is singing. But my favorite mysteries are “why-dunits.” These are puzzles solved not by the identity of the singer, but by the meaning of the sound.

Major why-dunits are more common than you might think. Let me put it this way: it’s difficult to take your camera to a local park and capture a bird plumage or behavior that has never before been photographed. But it’s about twenty times easier to make an audio recording of a call or behavior that has never before been audio recorded. And finding out what kind of sound you’ve recorded takes real detective work.

This is a dove detective story. A White-winged Dove detective story, to be precise.

Just the facts

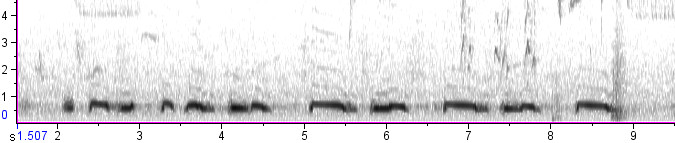

Unlike any other dove species in North America, White-winged Doves regularly alternate two different songs, a long one and a short one. The long one goes on for up to 10 seconds or so, ending with a distinctive sequence of alternating downward and upward voice breaks:

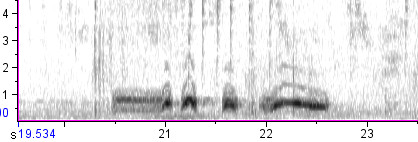

The short song is the four-note “who cooks for you?” phrase familiar to many people in the arid Southwest. Note the long, breathy introductory syllable, which is only audible at close range (this will be important later):

That’s what White-winged Doves should say, according to the field guides.

The Strange Case of the Two-note Song

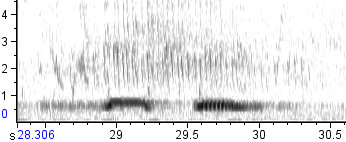

Where were you on the morning of May 16, 2009? I was in Guadalupe Canyon, Arizona, a few hundred yards from Mexico, recording a dove sound unlike any I’d ever heard, an odd two-note phrase with the second half burry:

Like any good gumshoe, I first eliminated the usual suspects. It wasn’t the usual song of the Mourning Dove (3-5 notes), Eurasian Collared-Dove (3 notes), Rock Pigeon (1 note), or Common Ground-Dove (1 note). Inca Doves sing two notes, but this wasn’t like the typical song or even the courtship song of that species either. I wondered briefly if it could be some rare vagrant from south of the border — Ruddy Ground-Dove, or perhaps Arizona’s first Red-billed Pigeon or White-tipped Dove — but no, I knew those songs and they sounded nothing like this.

The most likely scenario, then, was that I was hearing an uncommon vocalization type from a common bird. Most dove species in North America have multiple vocalizations, named by ornithologists for their function — an “advertising coo” to catch the ladies’ attention; a “display coo” to get them out onto the dance floor; a “nest coo” to entice them home to the bachelor pad. The “nest coos” in particular can sound quite different than the typical songs, and they are poorly represented in audio recordings. Was this a new “nest coo” for my audio collection?

Whatever the two-note dove was, it seemed to be countersinging with a White-winged Dove giving the typical short song. There were definitely two birds, because occasionally they would vocalize at the same time, but I could only see one White-winged Dove, and I couldn’t be sure whether it was making the typical song or the odd one. When it flew away, both songs ceased.

Searching for Clues

I went to the Birds of North America account for White-winged Dove to see if the two-note song had been described. But this only increased my confusion. The account clearly described the long song and the short song as different forms of the “Advertising Coo,” but its description of the “Nest Coo” was also apparently a description of the short song:

“Nest” call apparently very similar, consisting of 5 syllables, 3 in first half and 2 in second half, a single growling note (first syllable) followed by 2 barking notes (second and third syllables) connected together and with rising emphasis in second bark, then 2 barking notes together with a falling inflection and last one somewhat prolonged ( Whitman 1919, Goodwin 1983).

The five-syllable “nest call” starting with a “growling note” is pretty clearly just the short song heard at close range.

There was no mention of two-noted calls or burry notes anywhere in the article. I had to consign my weird recording from Arizona to the “unsolved mysteries” file until more information came along.

Reopening a cold case

In Mexico in 2010, I wandered for two weeks among courting White-winged Doves. I didn’t hear or record the two-note song again, but I did find some clues that began unraveling the mystery.

For one thing, I witnessed courtship displays of White-winged Doves for the first time, as described in the BNA account:

Male perches on sturdy twig or branch while female rests nearby, watching behavior. Male lowers body forward, head almost below level of perch, raises wings straight up and over body, lifts and fans tail, and rocks backward to normal perching position.

What the BNA account barely mentions is that the male gives the short song as part of this display. From the vocal notes on one of my recordings:

He’s sticking his wings out at a 45 degree angle above his body and a little bit in front of his body. They go up at the very beginning of his call, during that first note. They come down slightly emphatically right at the beginning of his second note, at the beginning of the “cooks” note. They’re kind of held stiffly there for that brief moment in between. He’s orienting a couple different directions as he does this; he’s got his tail kind of stuck up into the air.

That flick of the wings at the beginning of the short song has the effect of flashing the white wing patches conspicuously, so that the audio and visual parts of the display are closely coordinated. The BNA account suggests that both the long and the short songs may be used in courtship, but it gives few specifics. I never heard the long song in conjunction with a visual courtship display. All of this suggests that the short song might best be described as the “Display Coo” rather than the “second Advertising Coo” — though it is certainly given in many contexts other than the display, and far more frequently than the “Display Coos” of other dove species. If the short song is equivalent to the “Display Coo” of other doves, then the rare two-note call could perhaps be the equivalent of the “Nest Coo.”

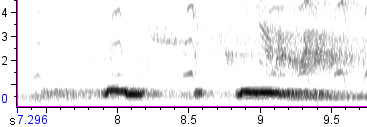

But another clue from Mexico might point in a slightly different direction. As I was recording another courting male White-wing, I realized I was hearing two birds duetting from somewhere up in the tree, although only the wing-flashing male was visible. One of the birds was doing the normal four-note short song, and the other was giving an abbreviated three-note version:

This three-note song is clearly intermediate between the two-note Arizona recording and the typical short song. The first note is almost identical to the Arizona bird’s: a breathy growl becoming a coo with an upward-and-downward voice break. The last note is slightly burry. Take out that short middle note, and you’ve got a pretty close match to the mystery two-note song.

During this observation, I got the impression that the bird doing the wing-flashing was also the one producing the three-note song, but I couldn’t be entirely sure of that. If I was mistaken, then it might have been the hidden bird, presumably a female, making the three-note song. And that correlates with another clue hidden in the BNA account:

Female call is lower in volume, shorter, and slurred (Viers 1970).

No more details of female calls are mentioned, including whether they resemble the long song or the short song or both, or whether they may be given in response to the courtship displays of males. We’re left with three possible explanations:

- The two- and three-note songs may be given by males in courtship. However, the four-note short song is also clearly given in this context, among others, which would mean the two- and three-note versions might be individual variants of or perhaps excited versions of the short song.

- The two- and three-note songs may be the “Nest Coos” given by males. However, both recordings I have of the shorter songs occur during duets, which is rather odd for a “Nest Coo.”

- The two- and three-note songs may be the female version of the short song, given primarily during courtship duets. This contradicts my impression that the wing-flashing male in Mexico was the one singing the modified song, but I may have been wrong about that.

The Big Reveal

I promised you a mystery, not a solution. I don’t know which of the three interpretations is correct. That will take more data, probably more observations and more recordings. It’s another terrific example of how little we know about the sounds of some common birds, and how difficult it can be to try to match the descriptions of earlier naturalists with one’s own recordings and observations.

It’s also a terrific testimony for the importance of behavioral notes on audio recordings. Most of the amateur sound recordists I know don’t spend much time talking into their microphones at the end of each cut, but they should. Talk about what the bird was doing while you’re still in the field, when you’ve just watched it happen, before you head home and forget the details. Specific behavioral information is more important than any other type of information you record.

Above all, this is a demonstration of the way in which I answer my own questions about bird sounds — by trying to cross-reference field observations, recordings, the scientific literature, and my own intuition. It can be frustrating to spend so much time researching a vocalization without being able to come to one solid answer. But it’s also thrilling to be this close to the forefront of knowledge, just because I was willing to spend time trying to answer a simple question about a common bird.