Hearing Loss and Bird Sounds

In honor of Earbirding’s first birthday (yes, we went live one year ago today), I’m posting on the topic of getting older — and losing your hearing as you age.

Age-related hearing loss, or presbycusis, happens to almost everyone to some degree, although it tends to be more severe among men, and susceptibility can run in families. It runs in my family, for better or for worse — even though I’m not yet 35, when I go birding with my friend Walter, he can detect chickadees by ear at twice the distance at which I can hear them. The other day, he and I watched a Blue-gray Gnatcatcher vocalizing at a distance of about 50 meters. He could hear it distinctly; I watched the bird’s bill opening and closing in silence.

Age-related hearing loss tends to affect high frequencies first, so that the upper frequency limit of a person’s hearing tends to decrease over time. A European inventor exploited this fact to create a device called “the Mosquito,” a type of sonic “youth repellent” that keeps bus stations and storefronts free of loitering juvenile delinquents by emitting a piercing high-pitched frequency that only young people can hear. (In retaliation, young people have converted the “Mosquito’s” buzz into a cell phone ringtone that their aging teachers can’t hear when it rings in class.)

In the past I’ve written about some corrective technologies for birding by ear. Today I’d like to give those of you with perfect ears a chance to experience partial hearing loss. It’s easy to filter out the high frequencies of bird sounds to get an idea of what you would hear if they were missing. Some songs, like those of the Golden-crowned Kinglet, would disappear entirely. Click on the link to test your hearing — if you can still hear the kinglet’s song, then your ears are pretty good. I can still hear high-pitched songs like this just fine, as long as they are at close range.

But there are other ways that hearing loss can affect our perception of sounds besides eliminating the songs entirely.

Losing Songs in Pieces

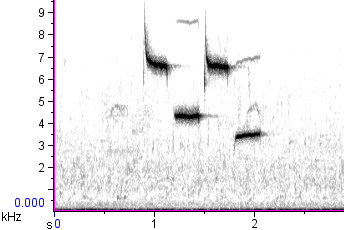

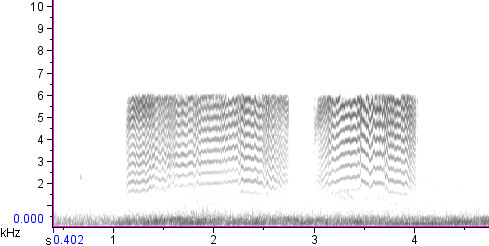

Some bird sounds are composed of both high- and low-pitched notes, so that those with presbycusis may hear parts of the sound and not others. A great example is the typical “fee-bee, fee-bay” song of the Carolina Chickadee, which is one of the best ways to distinguish it from the lookalike Black-capped Chickadee, which sings a simple “fee bee.” The complete song is easy to identify:

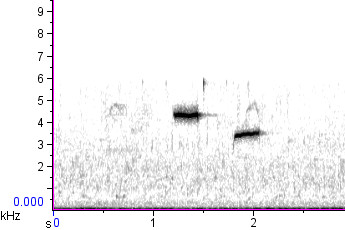

But those with an upper hearing threshold of 6 kHz, which constitutes only a moderate hearing loss, will hear just the two lower notes:

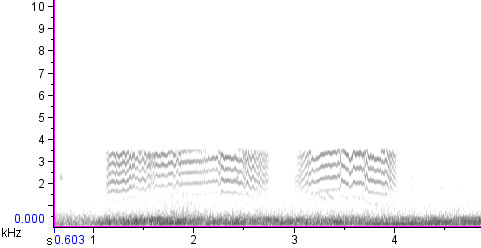

And that makes it sound much more like the Black-capped Chickadee:

Hearing Loss and Tone Quality

I used to be skeptical that presbycusis could affect the tone quality of sounds, but in some cases it can, especially if the sound is highly nasal.

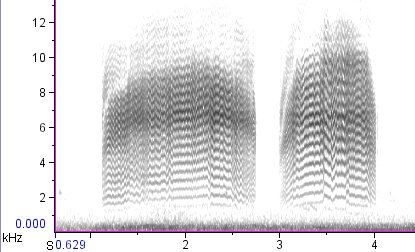

Here’s a quick reminder in case it’s been a while since you visited the page that explains the nasality of sounds. To have a nasal tone quality, a sound must be harmonically complex. Such sounds appear on the spectrogram as vertical stacks of lines. If the darkest lines in the stack are at the bottom, the quality of the sound won’t be nasal at all. The higher the darkness climbs, the more nasal the sound. Thus, the call of the California Gnatcatcher sounds intensely nasal:

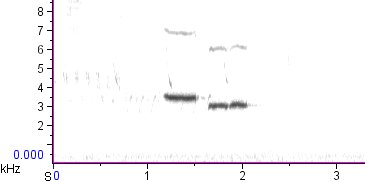

Here’s the same sound, filtered above 6 kHz. Note that the basic sound remains the same, but the quality changes slightly. However, I’d still call it “nasal.”

Here’s the sound filtered about 3.5 kHz. (This is about the same level of high-frequency filtering forced on all of us by our telephones. If you’ve ever wondered why people’s voices sound slightly different over the phone, it’s because the phone companies decided long ago that those higher pitches were mostly unnecessary to human speech, so they simply aren’t transmitted.) This version of the call maintains its basic pitch (because pitch is determined by the spacing between the partials), but the quality is muted, duller, and less nasal.

4 thoughts on “Hearing Loss and Bird Sounds”

Thanks for posting this Nathan, I have had hearing loss since I was thirteen due to multiple ear infections but it seems to be getting worse by age. I will play this for my son who is nine and can’t quite understand why his dad can’t hear what he can.

When several Cassin’s Sparrows showed up near Boulder last summer I went to see them and made a recording on my voice recorder. When I played it back I thought the song ended with two notes at 3.5 kHz. It wasn’t until I made a spectrogram that I realized that the song ended with two additional notes at around 8.9 kHz. I played it back again and could barely hear them with more volume. At 59 I’m glad I can hear as well as I can.

Great post, Nathan. I had the opportunity to take an older gentleman from Montana out on a trip a couple years ago in May, and he wanted to get a few remaining lifers for his Colorado list. One of them was Marsh Wren, and I took him to Lower Latham Reservoir where Marsh Wrens are right next to the road.

We stood out there for 5 minutes as I tried hard to point out the wrens to him. They aren’t always easy to see, but they sing like crazy, and it occurred to me then in a way that had never occurred to me before that not everyone can hear like I can. He strained and strained and just could not pick up the buzzes and trills of the Marsh Wrens. I felt terrible for having just assumed that it would be as easy as it is for me.

In an unrelated note, I head out to Tahoe this Friday to do the Cornell sound recording workshop. I’m stoked! Thanks again for providing the encouragement to follow through with this. I hope this starts a whole new way of appreciating birds, and hopefully contributing to our knowledge.

I have encouragement to offer. I commute to work by commuter rail and often walk on urban streets where high-pitched brake noise is common. I had noticed a loss of hearing in the high pitched range, and determined to preserve what I had left regardless of how I look to others. For about three years now, whenever a train pulls in or a bus brakes nearby, or when the subway goes around a curve, my fingers are firmly in my ears. The result has been way beyond my hopes. My hearing has become much more acute. That squealing noise now gives me genuine pain. Out birding, I believe that my hearing is as acute as 25 years ago. The changes were very gradual; I wan’t sure it was working for at least a year. The bottom line is that the nervous system is very adaptive if some of the cells are still alive.

Comments are closed.