The “Western” Flycatcher Problem

In 1989, the American Ornithologists’ Union split the Western Flycatcher into two species: Pacific-slope Flycatcher (Empidonax difficilis) and Cordilleran Flycatcher (Empidonax occidentalis), on the basis of vocal differences, differences in allozyme frequencies, and an area of sympatry in the Siskiyou region of northern California, where they were reported to mate assortatively.

Ever since then, these two species have been causing headaches for birders all across western North America. The conventional wisdom is that they are impossible to identify by plumage or structure, even in the hand. Voice is the only field mark.

Male position note

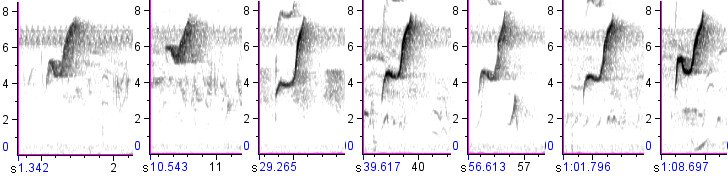

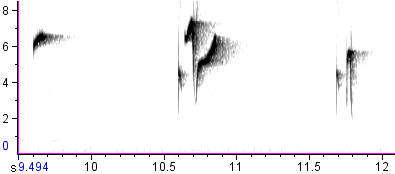

Most birders use only one clue to identify these two species: the subtle but distinct difference in the position notes of the males. Pacific-slope gives a one-syllabled upslurred whistle, and Cordilleran gives a two-syllabled upslurred whistle:

In “classic” examples like those above, note the distinct kink near the beginning of the Pacific-slope call, and the distinct break in the Cordilleran call (which can sometimes be rather indistinct, as it is in the second call on the right-hand spectrogram above).

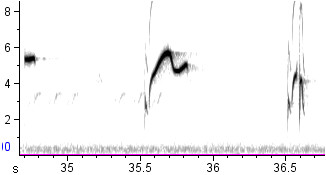

However, the situation with these call notes is quite messy. For one thing, the calls are frequently variable within individual males, as in these examples:

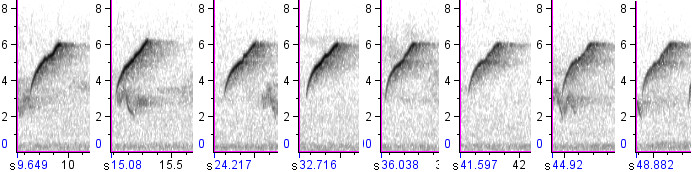

Some of the Pacific-slope examples above sound vaguely two-syllabled, and some of the Cordilleran examples sound distinctly one-syllabled. Here’s a more extreme version of the monosyllabic call type from a Cordilleran on territory in Colorado:

Note the lack of the distinct kink on the spectrogram that is typical of Pacific-slope. That kink, however, makes little difference to the human ear, and birds that sound like this are likely to be identified as Pacific-slopes in the field.

I believe that’s what happened yesterday when a potential first state record Pacific-slope Flycatcher was reported yesterday in Gregory Canyon, here in Boulder, Colorado. I went to record the bird this morning, and captured a few of its calls on tape:

Dawn songs

Less well-known than the differences in position note are the differences in the male’s dawn song, which is usually given only before the sun rises. As with the position notes, the differences in dawn song are subtle and subject to both individual and regional variation.

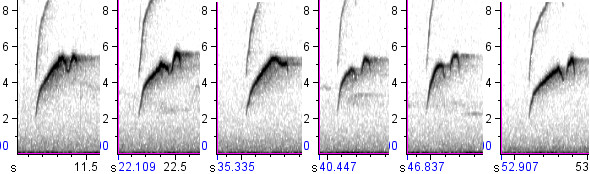

Like the songs of Dusky and Hammond’s Flycatchers, the dawn songs of Pacific-slope and Cordilleran Flycatchers consist of three different phrases usually repeated in an “ABC” pattern:

Compare each note of the songs:

- In both species, the first element of the dawn song is a brief, high-pitched, simple whistle of variable inflection.

- The second element is the loudest, longest, and most distinctive: in Pacific-slope it usually sounds vaguely two-parted (or at least split in the middle by a consonant), whereas in Cordilleran it usually sounds like a single slurred whistle. (Thus, the distinction in this case is the reverse of that in the position notes.)

- In both species, the third song element is a clipped, lower-pitched, two-syllabled note; the second note tends to be higher than the first in Pacific-slope and vice versa in Cordilleran, but this difference is somewhat variable.

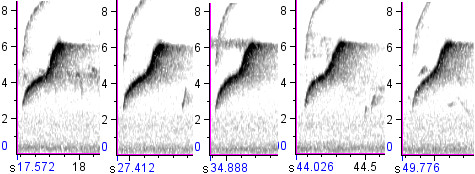

When I originally recorded the putative Pacific-slope Flycatcher in Gregory Canyon this morning, I thought I was hearing the standard Cordilleran dawn song from it in addition to its Pacific-slope-like position note. Upon examining the spectrograms of my recordings, however, it became clear that the bird singing the dawn song and the bird giving the position note were different individuals, since their vocalizations overlapped a number of times on the spectrogram. Thus, I do not believe that I heard dawn song from the Gregory Canyon bird this morning. However, I believe it can still be identified as a Cordilleran given the shape of its position note. Furthermore, I heard Cordilleran dawn song and Pacific-slope-like position notes from another individual male about half a mile farther up the canyon this morning.

On the whole, these two species, if they are indeed species, are exceedingly difficult to identify by ear. Spectrograms of the dawn songs or male position notes should be identifiable, however. Thus, decent recordings would be essential to document any occurrence of either species outside its normal breeding range.

Andrew Rush and Arch McCallum are currently researching these birds in great detail, so hopefully we will know much more about taxonomy and identification of “Western” Flycatchers in the next couple of years.

6 thoughts on “The “Western” Flycatcher Problem”

Outstanding work Nathan!

Excellent convincing detailed information and detective work Nathan!

Well done! The examples of individual variation are very instructive. Thanks for this post; I hope every birder in North America who thinks he or she can tell a Cordilleran from a Pacific-slope reads this. The reversal from disyllabic Song 2 to monosyllabic position note (Pac-slope) and its compliment in Cord is one serious bugaboo for those who think mono- vs. di- is all you need to distinguish these two, even though Chris Benesh posted on this years ago on ID Frontiers. A second bugaboo is the existence of that note that you recorded on 6/13. It’s rare enough that most folks don’t know about it, so thanks for publicizing it. But, it’s widespread, so it’s not even a sure indicator of a Cord if you record it. I don’t know if it’s a variant position note, or actually another call. It doesn’t really matter as far as identification is concerned.

A final bugaboo, of course, is that the distinctive position notes and dawnsongs where you live (Boulder) and those where I live (Eugene) are connected by a series of intermediates. I have a few of these on my website. If these are good species, where in fact do you draw the line? Andrew’s genetic analysis will presumably be the last word on that.

Good point, Arch. Johnson (1980) shows spectrograms of some Pacific-slopes from coastal California that lack the initial “kink” — and most of the Channel Island birds also lack it. Thus, birds giving calls with no kink and no break may simply be unidentifiable by that characteristic.

If the PSFL and COFL get lumped again, perhaps the new name will

be the Bugaboo Flycatcher.

A couple of other things to keep in mind… The ‘male’ position note is given by both sexes. I can say this without the slightest bit of ambiguity. How can I be so sure? Well, birds that I have recorded uttering the male position note have had ovaries in some cases. Also, the ‘female’ position note (what I call a ‘tink’, but others call a ‘seet’) is also given by both sexes. I have heard position notes like the 13 June ones above many times. In fact, some of them have even sounded almost siskin like to me at times. I have begun to wonder if these are female ‘male’ position notes, but I am not sure about that yet. These guys continue to surprise me with new squawks, squeaks, shrieks, etc. as time goes by.

Comments are closed.