Hummingbirds by Ear

Last week I had the pleasure of attending the 2011 Western Field Ornithologists’ Conference in Sierra Vista, Arizona, where the highlight of my trip was the opportunity to view and record huge numbers of hummingbirds. At our first stop, Beatty’s Guest Ranch in Miller Canyon, the legendary row of 15+ feeders was a blur of wings, with at least three or four dozen hummingbirds in view at any given moment, and others whizzing in and out at all times. It took mere moments to rack up a species list that included Magnificent, Black-chinned, Anna’s, Rufous, and Broad-tailed, Violet-crowned, and Broad-billed Hummingbirds.

Shortly, however, it became clear that the huge numbers of hummingbirds were both a blessing and a curse. For one thing, it meant that the number of difficult-to-identify females and immatures was immense. For another thing, it turned rarity-spotting into a search for a hyperactive needle inside a speedy, swarming haystack.

A few minutes into our field trip, one of the leaders, the eminent Kimball Garrett, called out “Blue-throated Hummingbird!”

“Where?” I asked.

“Didn’t see it,” he replied. “Only heard it.”

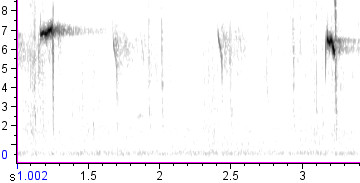

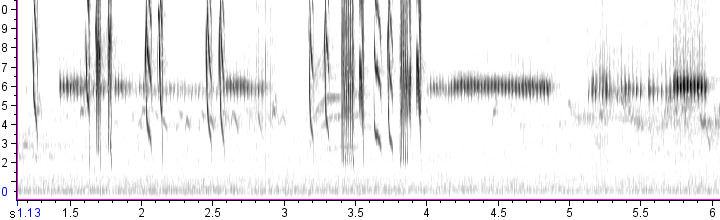

And then I was able to hear it too: a high-pitched, clear, brief, piping whistle, totally different from the chips, chirps, sputters and buzzes coming from the rest of the hummingbird crowd:

With my ears more fully open, I began to listen to the other species, and I realized that their vocalizations were distinctive too. In fact, within minutes, I could identify each hummingbird to genus (and therefore usually to species as well) just by hearing it call. After I had mastered the Blue-throated’s unmistakeable “seek!”, the next sound I learned to pick out was the strong, sharp “chip” of the Magnificent, which sounded to me more like the “tewp” call of a Black or Eastern Phoebe than like a hummingbird:

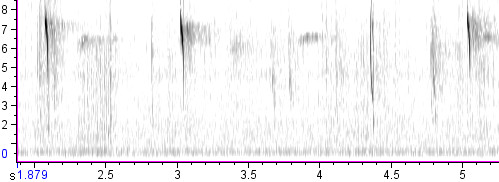

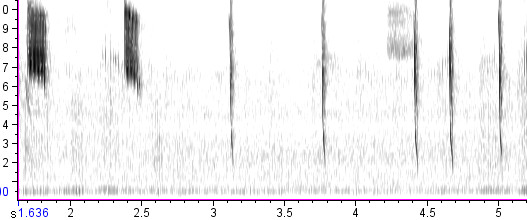

The calls of the Broad-billed Hummingbirds were also instantly recognizable: noisy “chit” and “chittit” notes, much like the calls of a Ruby-crowned Kinglet:

The Black-chinneds took a little more practice to pick out, but their calls were distinctive too, a slightly more nasal version of the standard hummingbird “chip,” reminiscent of tennis shoes on a gym floor:

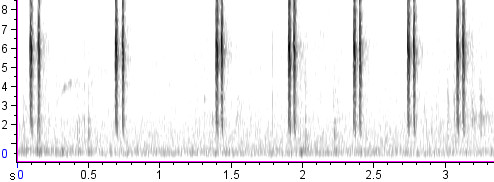

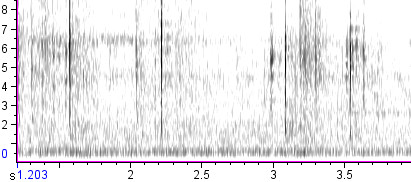

The genus Selasphorus, meanwhile, which includes Rufous, Allen’s, and Broad-tailed Hummingbirds, tended to give itself away by mixing short electric buzzes with other sounds (a variety of chips and twitters, plus the musical trills of the males’ wings):

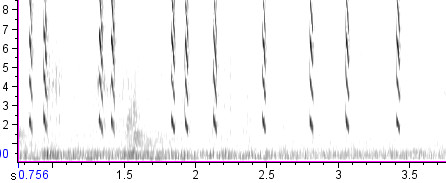

And the Violet-crowned Hummingbirds could be identified by their quiet, smacking “tik” notes, so brief that they barely show up on the spectrogram as hair-thin vertical lines:

With all these species shooting by at once, it only took me a short time to learn which was which, and arm myself with an identification tool of enormous power. “Black-chinned,” I’d find myself saying, even before the drab female hummingbird came out from behind the bush, much less landed on the feeder for binocular views. Suddenly I was performing feats of identification that had seemed like magic when Kimball Garrett did them a few minutes previously. And all it took was a little ear training!

4 thoughts on “Hummingbirds by Ear”

When I was in AZ a couple Augusts ago, some of the locals could ID hummers to species by the pitch (tone) of the wing whirring. Each species has its own pitch.

There was a great post by Ed Yong today on his blog Not Exactly Rocket Science. He talks about male hummingbirds’ unique tail songs.

http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/notrocketscience/2011/09/08/hummingbirds-dive-to-sing-with-their-tails/

I oftentimes struggle with Allen’s/Rufous IDs here in Southern California. I was wondering if you could point to any differences in their vocalizations/mechanical sounds that might assist with IDing these congeners. To me, it seems that both give the call that you describe as ‘zee-chuppity’ on your upload to Xeno-Canto. I have struggled to find consistent differences between the two.

Also, I would just like say I greatly enjoy reading your blog, I always learn a lot from reading your insights.

Cheers,

Nick

Hi Nick,

No vocal differences are known between Rufous and Allen’s Hummingbirds, as far as I know. The best way to tell them apart in the field — perhaps the only surefire way to identify them without exceptional, prolonged scope views of the outer tail feathers — is the difference in the display dives of the males. For one thing, they differ in aerial flight pattern — Allen’s begins with a series of back-and-forth shuttle motions across a horizontal distance of 2-3 meters, then rises slowly to a great height and shoots down along a J-shaped dive path. The shuttle motions are accompanied by loud, stuttering trills from the male’s wings, and the tail feathers make a high-pitched, musical whistle at the bottom of the dive (listen to it here).

Rufous, on the other hand, does multiple consecutive J-dives without the initial shuttle display, and the dive sound is different, a quick nasal stuttering sound that is reminiscent of the bleating of a Lesser Nighthawk.

Hope that helps!

Comments are closed.