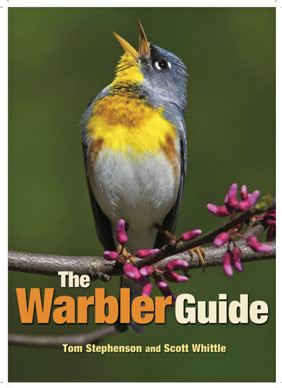

The Warbler Guide

(Updated 7/10/2013 to include discussion of the audio files now available for download)

(Updated 7/10/2013 to include discussion of the audio files now available for download)

Princeton University Press recently sent me a review copy of Tom Stephenson’s and Scott Whittle’s The Warbler Guide, published this month. This is one of the most remarkable books about bird identification that I’ve seen in recent years.

The quick summary:

- It’s huge. Only one inch shorter and 3 ounces lighter than the “big” Sibley Guide. You won’t be slipping it into your jacket pocket.

- It has TONS of photographs — 38 photographs of Blackburnian Warbler in that species’ account, not counting the blown-up vignettes and comparison photos of similar species, or the photos in the wonderful flight comparison plates at the back of the book.

- It’s got spectrograms — illustrating an average of 4 song types per species, plus the “chip” and the “flight call.” At last, a field guide that gives bird sounds the attention they deserve!

- It’s groundbreaking. There’s more information here on warbler identification than you can learn in a year (if you don’t already know it) — and the authors have come up with multiple original ways to present it, many of them quite brilliant.

Disclaimer

I got the fine opportunity to review this book in part because it puts so much emphasis on identification by sound, including by spectrogram — which is what this blog is all about. As you know, I’m currently at work on my own field guide to bird sounds. In some ways, The Warbler Guide treads some of the same ground, but it does so in its own way, and I have no connection to the authors or the publisher.

Visuals

The visuals in this book are tremendous. The quantity and quality of the photographs outstrips anything I’ve seen in a field guide.

Maybe the best part is the comparison pages, most of which are called “finder guides”. You want all the warbler heads on one plate? All the undertails? All the side views? All the song spectrograms? All the flight shots? This book’s got comparison plates for all of these and more. These pages alone are worth the cover price.

Layout

The book’s layout can be confusing, contributing to an overall sense of “information overload.” For example, the Blackburnian Warbler species account proceeds as follows:

- Pages 1-2: photos of bright Blackburnians;

- Page 3: more photos of bright Blackburnians, plus photos of some comparison species (in this case, Yellow-throated and American Redstart);

- Page 4: how to age and sex Blackburnians, plus range maps;

- Pages 5-6: spectrograms: Blackburnian on the left, confusion species on the right;

- Pages 7-8: photos of drab Blackburnians;

- Page 9: more photos of drab Blackburnians, plus comparison species;

- Page 10: a full-page photo of a Blackburnian, just to keep the number of pages even.

The design makes it hard to tell when you’re “home” in a species account — that is, when you’re at the beginning. And the ubiquity of comparison species, both in photos and spectrograms, blurs the borders between accounts even further. If you, like me, are in the habit of scanning photos rather than words when looking for a particular species, then abandon all hope of navigating this book with ease. (If you’re in the habit of scanning words, you’re still in some trouble, because all the photos are helpfully labeled.) The only thing that saves this book from complete organizational disaster is the decision to order the species accounts alphabetically rather than taxonomically. Normally I’m not in favor of this, but here, it’s a life-saver.

Spectrograms

The big news is that this book has spectrograms! That fact alone makes me want to shout with joy from the rooftops. At last we can see the sounds we’re describing. This is the first major attempt to use spectrograms for identification since at least the 1980s, and it is long overdue.

It’s also a watershed moment for birding by ear. A lot of people will use this book to decide whether spectrograms are worth using. I fervently hope they will think so. But based on the way the sounds are taught and presented, I fear that some readers, especially casual birders, may persist in the prevailing misconception that spectrograms are difficult, and “for experts only.” If this happens, it will be the fault of the authors’ vocabulary. A choice as simple as using the term “element” instead of “note” sends the message that song identification is a technical endeavour, not an intuitive one.

Their narrow focus on warblers both hurts them and helps them. It allows them to simplify the discussion to three tone qualities — “clear, complex, and buzzy” — which is a simple and helpful distinction. But the focus on warblers also tempts them to divide all songs into “phrases” and “sections.” This terminology is great for explaining the difference between, say, Nashville and Tennessee Warbler songs, but it becomes very awkward when applied to, say, Canada Warbler, forcing the authors to write “many Phrases, almost all 1 Element” instead of the much simpler “almost never repeats a note.” And their descriptions of “Expanded” and “Compressed” elements are so opaque that I fear they may do more harm than good. I fear the same for the section on distinguishing between flight calls.

Again, though, they get the visuals right. The spectrograms are high-quality, and underneath each one is a series of symbols intended to give a sense of how the song actually sounds. When it comes to the pitch and rhythm of the sounds, these symbols are pretty intuitive, and they had me hearing the sounds in my head almost immediately. I don’t know if they’ll work for everybody, but they might provide a “stepping stone” to help beginners translate between picture and sound.

Sounds

The book is accompanied by a downloadable playlist of audio files. In a couple of years, we’re going to forget that serious books on bird ID were ever published without accompanying audio files. And we’ll get used to paying more: it costs an additional $5.99 to download the audio collection. You can purchase it separately from the book if you like.

The audio collection mirrors the book exactly. The sound file named 180 a Blackpoll Chip Call.mp3 accompanies spectrogram a on page 180, making it easy to go back and forth between audio and book. If a particular sound appears more than once in the book (due to being included on multiple comparison pages), then it appears more than once in the audio collection as well. Unfortunately, the naming convention for comparison songs is confusing: 165 d Black-and-white Blackburnian.mp3 is the Blackburnian song shown on the comparison page for Black-and-white Warbler. There’s no Black-and-white Warbler in the audio clip.

The audio files are generally high in quality. They are very short — a single song or a single call — and have been assiduously cleaned of background noise. One really cool thing is that the audio files use spectrograms as the “album art,” so on most devices, the appropriate spectrogram pops right up when you play the song. This little feature, more than any other aspect of the entire project, has the potential to get people visualizing sounds and change the way they listen.

One downside to the audio aesthetic is that it forces a narrow focus on single songs. There’s little mention of patterns of delivery — whether consecutive songs are similar or different — which can be useful for ID at times. More distressingly, the single-serving recordings of chips and flight calls provide zero information about the range of variation in each species’ calls, and the careful scrubbing of background noise makes some of them sound unnatural. Compared to Evans and O’Brien’s CD-ROM of flight calls, The Warbler Guide’s recordings are far easier to listen to and compare. But Evans and O’Brien’s longer and more natural-sounding clips, even though they often roar with noise, provide lots more information to the ear.

Biology

This book is pretty much all identification, all the time. There’s very little about biology and behavior — only what the authors deem useful in identification. Many warblers employ a two-category song system, in which different categories of songs are deployed in different patterns for different purposes. The research into these song systems is extensive, complex, and mostly absent from this book. Many will applaud the narrow focus on identification, but I, for one, am sorry that the book teaches me little more about these fascinating birds than simply how to tell them apart.

The bottom line

All in all, this book is a must-have for serious birders. Beginning and intermediate birders should also check it out, and not be too discouraged by the sheer volume of information. I am confident that this book will enhance the way people look at warblers. I am less confident, but ardently hopeful, that it will enhance the way they listen to warblers as well.

5 thoughts on “The Warbler Guide”

Was also glad to see my old friend Catherine Hamilton get a shout-out on their website! Very talented artist…

I was intrigued by this book when I found out about it a little while back. Thanks for the useful review.

I have tried using my iPod to listen to the songs while reading the book. As you mention, the titles are confusing, and don’t display fully on my iPod anyway. By the time I sorted which song was playing and where it was in the book, it not only had already finished but had also finished the next dozen songs (each song is 2-3 seconds). So I just watched the album art spectrograms instead. I’ll have to use my computer in conjunction with the book rather than an iPod.

I’ve read through the section explaining the songs (Elements, etc), and will have to reread it again because when I turned to the song descriptions, I didn’t understand what they were talking about even though I know warbler songs themselves quite well. I appreciate the authors’ approach, but I don’t think making a new vocabulary solves more problems than it creates.

However, I consider these minor nuisances, and am enthusiastic about the book and the new approach. As I already identify warblers by sound/sight I wouldn’t use the book as a guide, but would use it as a reference when I want more information on song/plumage/age/sex-related characteristics. Plus, it is wonderful to lie in bed at night and just leaf through it to admire the pictures, learn a few new tidbits, etc. It also familiarizes me with the book and it doesn’t seem such a large jumble of overwhelming information.

The authors mentioned they have plans for an app. Based on their work in this book, I’d buy the app with no hesitation.

Incidentally, if people want to learn how to listen to birds, I think Donald Kroodsma’s book, The Singing Life of Birds and accompanying CD, is still unsurpassed. I’ve not listened to a robin (AMRO) the same way since.

I really enjoyed reading your review and now that I have had a chance to spend some time with my copy I agree with your analysis. There really is a lot of information jammed in there and it can get confusing at times though I feel like the more I work with the book the easier it gets. No surprise there. I am really interested in learning more about the biology and behavior of these birds. Can you recommend a book or other resource that might cover this aspect of wood warblers?

Thanks, Greg. I’d say a good place to start is Don Kroodsma’s Singing Life of Birds. It’s got a nice chapter on Chestnut-sided Warblers that introduces the research on warbler biology in a really accessible way.

Comments are closed.