Long Calls of Gulls

A couple weeks ago, I was puzzling over a group of distant gulls on a reservoir in Wyoming. I was fairly sure they were all the same species, but through my binoculars, I couldn’t quite decide whether I was looking at Ring-billed or California Gulls. Then, from across the water, I heard one of them give a hoarse, slow “koo-WEEE? kweee? kweee? … QUIRK! … QUIRK!” and I confidently checked the “Ring-billed” box in my checklist app.

As I wrote last year, most people don’t listen to gulls much. But as I’ve paid more attention to them over the past year, I’ve realized that many species can indeed be identified by sound alone, and this fact has greatly improved my birding skills. In today’s post I’m hoping to provide a basic framework for beginning to identify some of the species by sound.

What’s a “long call”?

The “long call” is the most complex vocalization in a gull’s repertoire, and one of the most frequently given. “Long calls” can be heard year-round in a variety of situations, but they most often serve as aggressive signals directed at other gulls. They vary within individuals based on excitement level, but individuals may be able to recognize each other by long call. The long calls of different species tend to sound rather different.

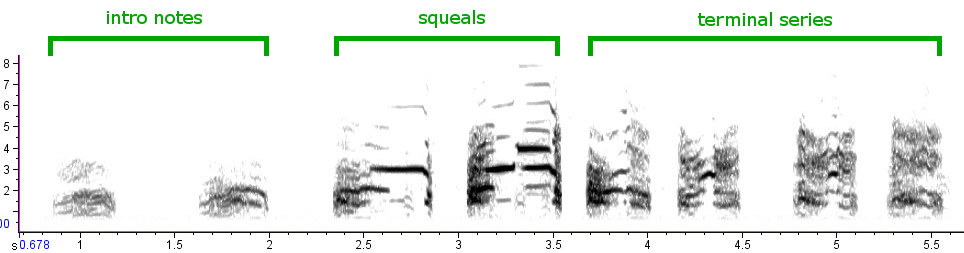

You can think of the archetypal “long call” as containing three parts:

- The intro notes are highly variable depending on the bird’s level of excitement, and are often totally absent. When present, they usually take the form of short barks, as in the example above; long mewing wails; or a mix of the two.

- The squeals are the start of the long call proper. They are by far the loudest, and usually the longest and highest-pitched, notes in the call, and they usually coincide with a distinctive motion of the head, such as a deep bow and/or a backward head toss. There are usually only 1-2 squeals, but occasionally three or even more if a bird is excited. (Some species don’t really “squeal” at this point in the call, but I couldn’t think of another good name for these notes.)

- The terminal series is the series of similar notes that ends the call. The number of notes varies with excitement level, but the sound and speed of the notes tend to be fairly consistent within species, making this generally the most useful part of the call in identification. Most species adopt an “oblique” posture for the duration of the terminal series (see Herring Gull photo above), but some, like Ring-billed Gull, give distinctive motions of the head with each note.

Most large North American gulls sort out pretty well into groups that follow similar patterns in their long calls.

- High yelpers, usually clear: Herring, Glaucous, Western, Glaucous-winged

- Low yelpers, often hoarse: California, Lesser Black-backed, Great Black-backed

- Slow squealers: Ring-billed and Mew

- Nasal: Heermann’s, Franklin’s, Laughing

The High Yelpers

These are the “classic seagull” sounds as brought to you by Hollywood. In this group, the terminal series usually consists of clear (not hoarse) high-pitched yelps, often without much change in pitch or speed. Western and Glaucous-winged average lower in pitch than the other two species, and tend to have simpler calls, very often omitting the intro notes and squeals. Glaucous and Glaucous-winged average slower than Herring and Western, with fewer notes per call. However, individual variation often makes it difficult to tell these four species apart by vocals alone.

The Low Yelpers

This group resembles the first group, except that the pitch of the terminal series averages lower and more nasal (almost more “bugling” than “yelping”), and there is a much greater tendency towards hoarse or harsh tone qualities. Great Black-backed tends to be the lowest of these.

The Slow Squealers

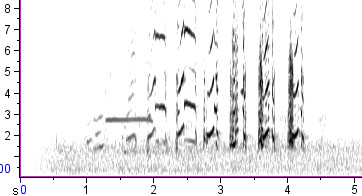

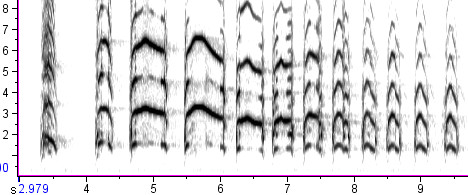

|

|

|

| http://earbirding.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Ring-billedGull_04_longcall_RBGUlongcall2_SPlatteAdamsCO_NDP2013-01-14_ii.mp3 | Click here to listen |

These two closely related species have a distinctively slow delivery — typically about two notes per second in the terminal series. The pitch tends to be high and the quality rather squealing. Tone quality separates them: Ring-billed’s voice is distinctively scratchy or screechy, especially in the terminal series, while Mew tends to have a much clearer tone. In Ring-billed, at least, each note in the terminal series is usually accompanied by a distinctive vertical pumping of the neck with the bill held skyward, as though the bird were jabbing its bill at an airborne opponent with each cry.

The Nasal Gulls

Laughing and Franklin’s Gulls were recently moved from the genus Larus into the genus Leucophaeus, reflecting our understanding that they are not closely related to the other gulls on this page. Their immediately distinctive voices, high-pitched and nasal, are evidence of this evolutionary distance. Their long calls are also unique in structure, lacking the “intro>squeal>series” pattern of other gulls. Laughing Gull is the only gull that consistently starts with a fast series of notes followed by a slow series of notes. Franklin’s, meanwhile, usually gives a simple slow series of rising notes at one speed. The fast notes of Franklin’s, if they occur at all, usually come at the end.

Then there’s Heermann’s Gull. There’s no mistaking it for any other West Coast species. Imagine the long call of a Herring Gull, as performed by a Red-breasted Nuthatch:

There’s a lot more to gull vocalizations, but hopefully this post can get people started on what to listen for. I still have a lot to learn about identifying these birds by sound, and I’d be glad to get your insights in the comments.