How to Identify a Timberline Sparrow

It’s hard to deny – among many birders there is a preconception that sparrows are brown and boring looking. And while I would argue that point for many of the species in the group, it isn’t very easy to defend Brewer’s Sparrow (Spizella breweri). It’s a small, brown, and subtly marked bird that doesn’t stand out much when you see it. But just wait until you are standing on a sage flat in the pre-dawn and hear a Brewer’s Sparrow! There are few auditory experiences in the west as sublime as being out in the crisp, cool air, surrounded by the smell of sagebrush, and hearing the tinkling buzzes of Brewer’s Sparrow all around you.

In addition to having one of the best voices in the west, Brewer’s Sparrow also has an interesting taxonomic facet to its name. The nominate breweri subspecies is familiar to most anyone who birds in the appropriate habitat. Less well known is that there is another subspecies – taverneri – that was first described as a separate species from far to the north of most Brewer’s Sparrows (Swarth and Brooks 1925). Unlike the nominate subspecies, it is restricted to stunted, willow-dominate thickets right below treeline – hence the common name of “Timberline” Sparrow. It was later lumped with Brewer’s Sparrow, but recent morphometric and genetic studies have again raised interest in the form (see Klicka et al 1999). For a long while conventional wisdom said that Timberline Sparrow occurred only well north of Brewer’s, in an isolated range centered around southern Yukon. But as more people studied the bird it was found to also occur near treeline further south, first in the Canadian Rockies, and then in Montana. Birds have been found in similar habitats even further south, to at least southern Colorado, but it is less well known what to make of these birds (more on this later in the post).

Before I dive into the vocals of these birds, a bit on the visual identification. As Brewer’s Sparrow doesn’t have much in the way of obvious field marks under the best of circumstances, it shouldn’t come as any surprise that telling Timberline from the nominate isn’t easy by any means. The most often cited field marks are usually bill size (Timberline has a longer but thinner bill), strength of the face pattern and crown streaking (noticeably stronger in Timberline), overall color (noticeably grayer in Timberline), and sometimes some faint streaking on the flanks or sides of the chest in Timberline. All of these marks are hard to use in isolation, at least for someone without a lot of experience with both forms. Personally, I believe that if I spent time closely looking at migrant or wintering Brewer’s Sparrows I might be able to find birds that I have a strong suspicion are Timberlines, but that I wouldn’t be able to make a claim with certainty.

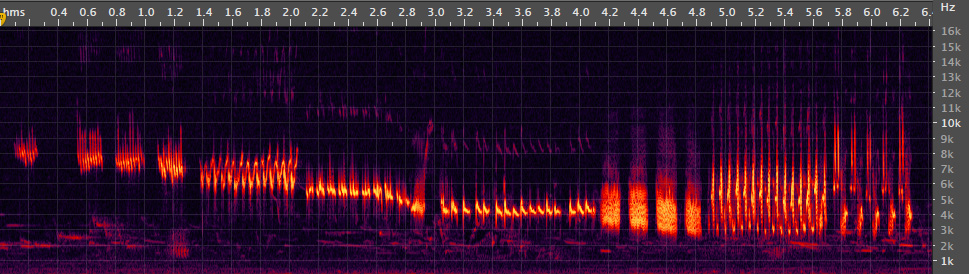

Enter vocals. Differences in the song between Brewer’s and Timberline are the most often cited difference between the two. Before getting into the nitty-gritty of it all, though, we need a bit of a primer in the sounds that Brewer’s Sparrow (sensu lato) make – it’s more complicated than just song and call. That wonderful dawn chorus I mentioned in the intro to this post is what is known as the “long song” – a successive series of different trills, typically starting out very high-pitched and then descending into a long string that can sometimes last 20 seconds or more. Mostly given very early in the morning and late in the evening, it can sometimes be heard at other times of the day but generally less often. Below is an spectrograph of long song from Mesa County, Colorado, to demonstrate the structure of the voc.

The other song of the species is appropriately known as the “short song”. This vocalization, much shorter than long song, is typically comprised of one to three different trilled phrases, each phrase most often (but not always) even in pitch, but different in pitch from the previous one. It is also one of the most variable songs in the west – some birds can sound startlingly like Chipping Sparrow, while others incorporate elements almost reminiscent of Prairie or Blue-winged Warbler songs. When you hear a Brewer’s Sparrow during daylight hours it is much more likely to be giving this vocalization than the long song, though again there are exceptions to this. Most Brewer’s Sparrows only have one short song that they give, whereas long song can be variable in terms of which trilled elements they include. If you want to read more on the different song types, Arch McCallum has a page dedicated to the topic here.

Like most other sparrows, Brewer’s also has various calls – flight call, chip call, twitter, etc. I don’t really go into those here, in part due to very small sample size available from Timberline Sparrow of these calls, and also since I don’t personally believe that they can be identified to form.

Of the two song types, it is long song that I believe is most readily distinguishable between the two forms. The “classic” long song of breweri typically sounds very buzzy throughout, descending from very high-pitched, insect-like buzzes to lower pitched buzzes, but rarely having anything that one would describe as “musical” about them. This is due to the broadband nature of all of the elements of the song. Most phrases in the long song are made up of two alternating notes that comprise the buzz, and in nominate breweri both of these elements are broadband, or if one is less so then the broadband one dominates. Below are several examples of long song from breweri from around their range.

The long song of Timberline Sparrow, on the other hand, gives a much less buzzy impression. The overall structure of the song is the same – it typically starts out with very high-pitched, insect-like phrases that quickly descend into the variable series of trills. The difference comes in the fact that elements of the majority of the phrases in the song are noticeably less broadband than in breweri, so that they sound more musical and tinkling. This difference isn’t huge, and there is considerable variation, so it is important to listen to enough of the song to get a general impression rather than make the call on just one or two elements. In general, though, I think that once you’ve gotten a handle on how each subspecies sounds when long singing you can tell the different most if not all of the time. Listen to several examples of Timberline Sparrow below (from four different birds; the first three are from the same individual in the Yukon, the next five from different birds in Alberta) and see if you can tell the difference:

When it comes to short songs, these differences can also apply. Unfortunately, short songs seem to be a less reliable way to distinguish Timberline from Brewer’s. The main reason for this is probably that in long song there are lots of difference elements and the impression the entire vocalization gives is a composite of how they sound, whereas in short song you only have a few to draw on. So say you get a Brewer’s on the musical end of the range of variation and a Timberline on the buzzy end there could be some overlap. That said, I do believe that on average the short songs of Timberline are less broadband and more musical. First, here are a variety of breweri short song, both on the buzzy and musical ends of variation:

And here are two examples of Timberline short songs, one on the musical end and one on the buzzier end:

So by now you’re thinking “great! Now I can easily tell the difference between Timberline and Brewer’s, at least by the long song”). Unfortunately there’s reason to be cautious; the differences between these two forms aren’t entirely black and white. There are some recordings out there of breweri that are less buzzy than average, approaching Timberline. And when you listen to the long songs of Brewer’s that I link above you can hear that the examples from California seem to be a bit less buzzy than those from Colorado. When you combine this with a relatively small sample size of available Timberline Sparrow recordings and it’s hard to be completely certain how reliable the vocal differences are. That said, I personally have never heard a Brewer’s Sparrow that sang a long song entirely like that of the Timberline Sparrows I’ve heard. But if you’re investigating a suspect bird on territory out of the known range of one form or the other, I would want more than just one line of evidence before making the call.

This is especially relevant to birders in states where Brewer’s Sparrows have been found breeding near or at treeline but south of the known range of Timberline Sparrow. A few years ago there was a lot of buzz about this issue in Colorado, where I am from. Most birders in the state accepted that these birds breeding in highland stunted willow patches were a southern range extension of Timberline Sparrow, and that they were different than the more widespread Brewer’s Sparrow they were all familiar with. And I’ll admit I was also in that camp, at least to start.

But then back in 2007 I actively tracked down two different populations of these highland birds. I was rather surprised, at the time, at how un-different they were. The first group I recorded all sang songs that sounded unremarkable to me. In the second group, though, I did find a bird that was noticeably more musical and stood out, but it was surrounded by birds that were “normal”. Here’s the recording I made of that more musical sounding individual. Sounds a lot like Timberline Sparrow, doesn’t it?

What was going on? To this day I am not entirely sure. At the time my theory was that lowland breeding breweri moved upslope after their first brood to breed in dry stunted willow habitat superficially similar to the sage flats they used lower down. But now I am unsure. I didn’t record any long songs from either of those populations, and knowing what I do now after having more experience with definite Timberline Sparrows I am unwilling to make a call until I record some long songs from these southern highland birds. It remains one of those exciting areas that needs to be looked into, a place where anyone with a recorder willing to make the effort to be standing on a high-mountain hillside waiting for the dawn can help unravel a mystery.