New Crossbill Compendium

Ken Irwin is a household name — at least among the bedlamites who think untangling the mysteries of Red Crossbill call types is a fun and worthwhile activity. Ken has haunted the seaside spruces of California’s Patricks Point State Park for years, tracking the Red Crossbills that wander in and out of the park, recording their vocalizations, capturing and measuring them, and following their nesting cycles. According to a couple of people I talked to, he may know the individual birds by name, and rumor has it that he is close to being accepted among the crossbills as an adopted member of their tribe.

Ken is best known for discovering a new call type (Type 10), and his paper describing it is coming out in the next issue of Western Birds (which, incidentally, will also include an article on phoebe vocalizations by Arch McCallum and me — more on that later). When I talked to Ken on the phone last year, he was also hard at work on a website that would include sound files of all the types, their excitement calls, their begging calls, their songs, etcetera.

Now that website is up, and everyone interested in crossbills should go see it. It’s a work in progress — but even in its current form, at about 14,000 words, it’s more than a little overwhelming. Nevertheless I recommend girding your loins and wading in. Irwin’s site is the most important addition to the web-based crossbill literature in years.

The recordings are probably the most important contribution made by the site, and they are both good and bad. Here’s the good news:

- there are a lot of them;

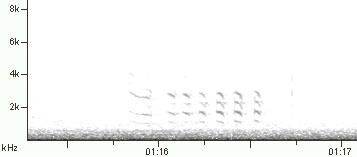

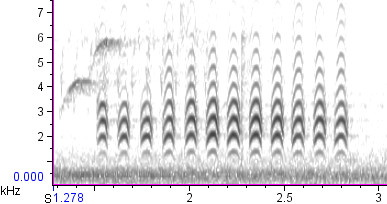

- they put Type 6 and Type 7 on the web for the first time (outside Jeff Groth’s original site from 1996, where all the recordings are so short and so heavily edited that they don’t really count in my opinion);

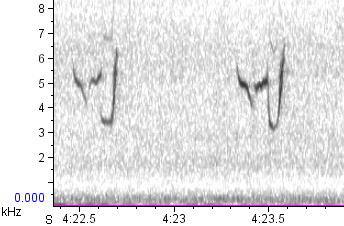

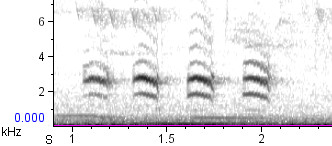

- there are several nice head-to-head comparisons of different types;

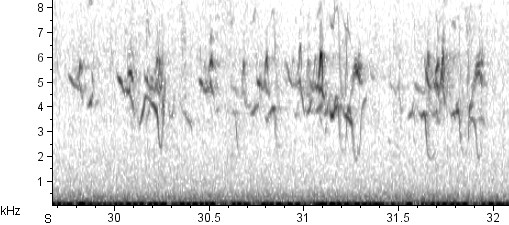

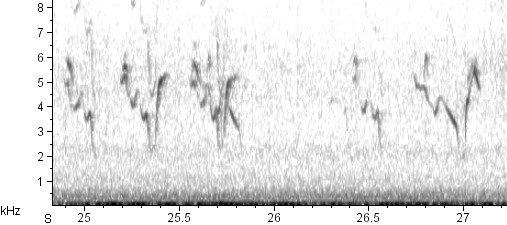

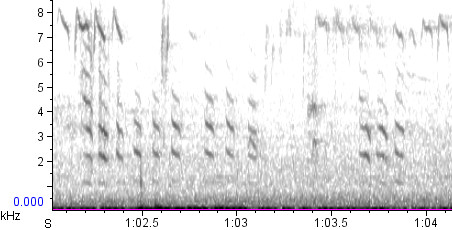

- most of them include lots of examples of individual birds, so that you can quickly get a strong sense of the limits of individual variation within the types;

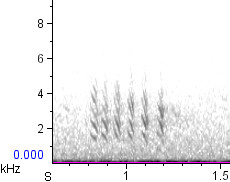

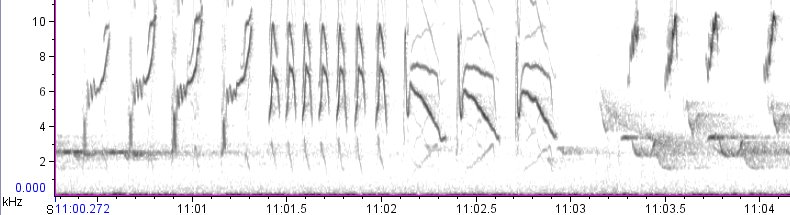

- they include many recordings of lesser-known vocalizations like excitement calls or “toops”, chitter calls, and songs.

Here are some things I liked less about the site:

- The organization is confusing, and it got more so as the page went on. The information on this one page should have been split onto several linked pages, and was apparently intended to be. This may improve with future revisions.

- Personally, I feel that Irwin’s word descriptions of the different calls are uneven in quality and ultimately unsuccessful, but then I have this reaction to most word descriptions of crossbill calls.

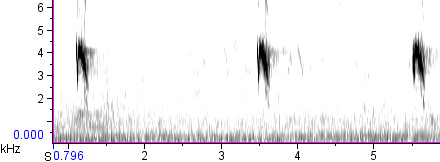

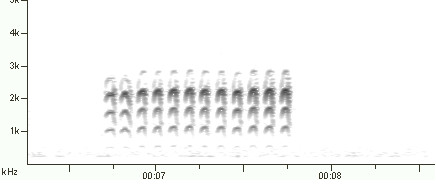

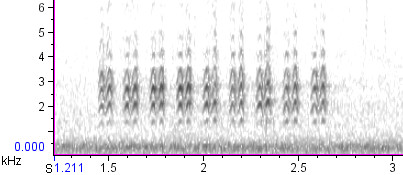

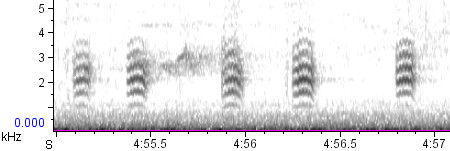

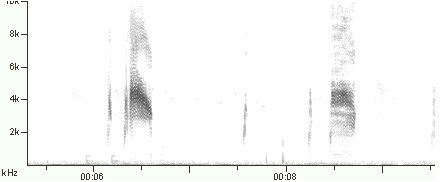

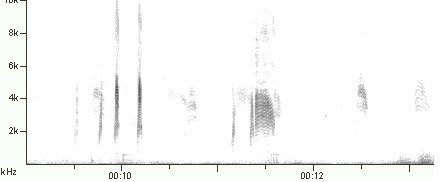

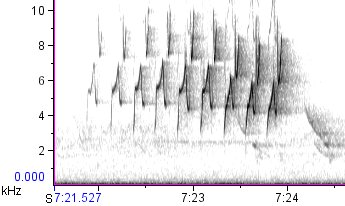

- The recordings have been a little too heavily edited for my taste, so that the birds sound too mechanical, not quite like they would in the field. Since Irwin typically includes 2-3 calls per individual bird, the overall effect is much better than that of Jeff Groth’s site, but if he had included longer cuts with less editing, I think his recordings could have been even more useful.

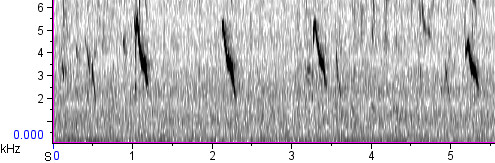

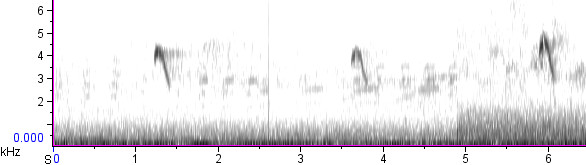

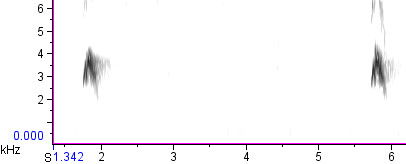

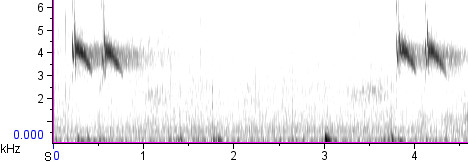

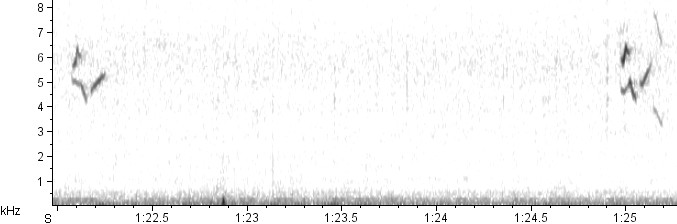

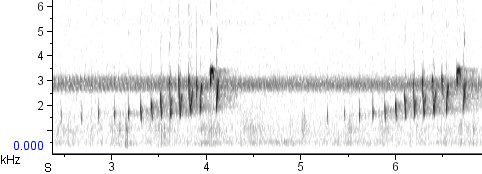

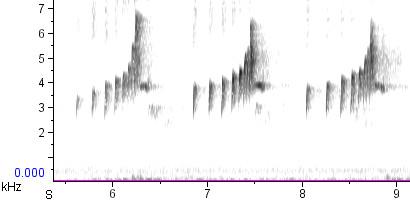

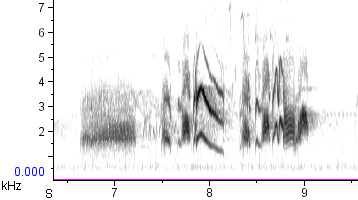

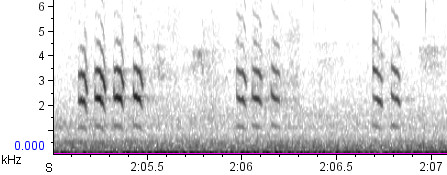

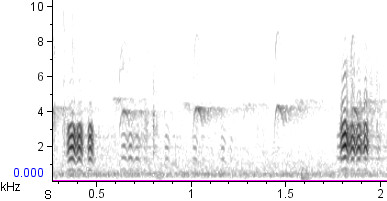

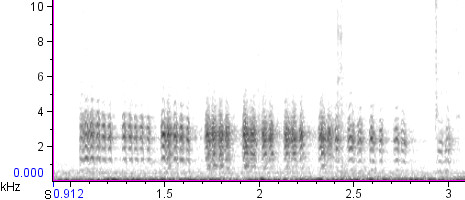

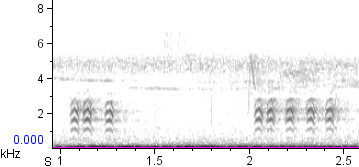

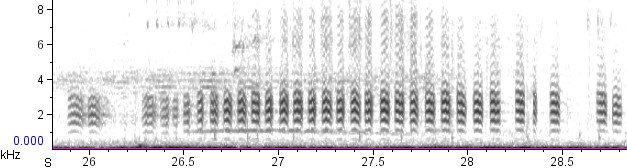

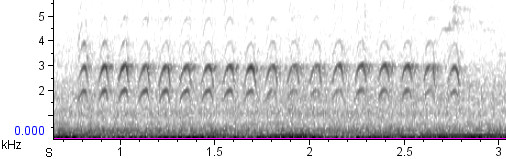

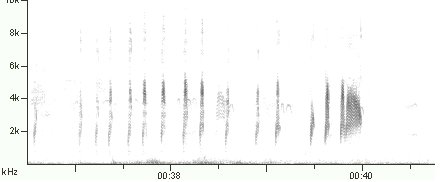

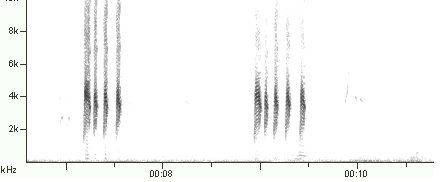

- The spectrograms are full-contrast — bicolored black-and-white instead of grayscale — and therefore less informative than they should be.

When it comes to the science — the validity of Type 10 in general, Irwin’s boundaries for Type 10, and his conclusions regarding crossbill song — I’m going to have to postpone judgment for a while. When I see his Western Birds paper, I’ll post again. Until then, when you’ve got a little free time and extra brainpower, head over to his page and start the long process of digesting the enormous amount of information that he’s published — and thank him for it if you get the chance.