That’s No Starling

I have a confession to make.

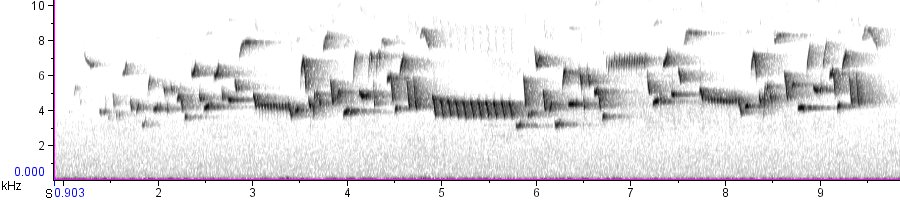

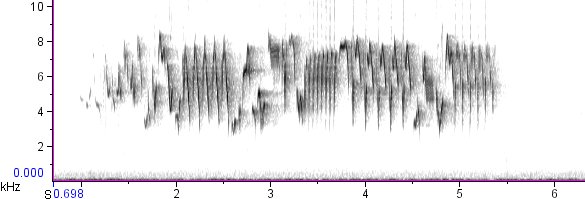

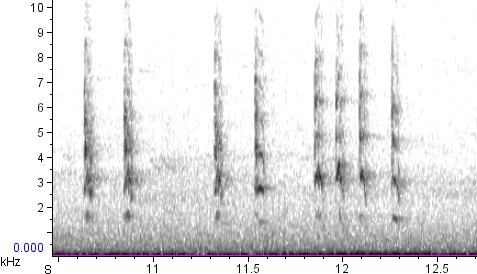

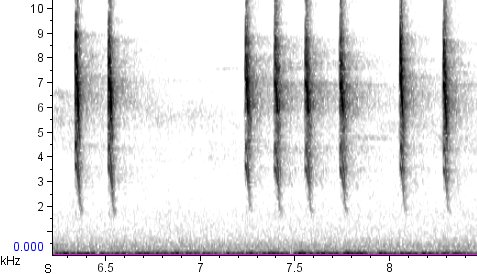

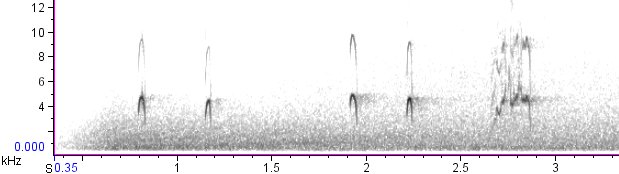

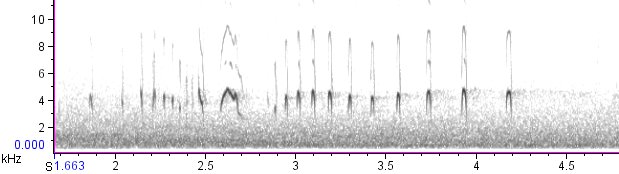

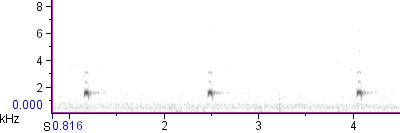

For six years now, after my morning commute, I have parked below Folsom Field, the football stadium of the University of Colorado, and walked around the edge of it on my way to my office. Frequently, I used to hear this odd bird singing from somewhere up on or near the roof of the stadium:

I could never see the bird; it always sounded echoey, like it was inside the roof of the building. Sometimes it would sing in the mornings, but more often it would sing at night — sometimes all night, as far as I could tell. Fall, winter, spring, no matter: the unseen singer was belting it out.

The bird sang in bouts consisting of series of notes; it had at least eight different note types, many of which sounded screechy, and some of which were dead on for European Starling. Some of its note types sounded like mimicry — of birds like American Kestrel, Cooper’s Hawk, and Red-shouldered Hawk — which also pointed to starling, as did the singer’s habitat (the roof of a building in a predominately urban environment) and its insomnia.

So I just figured it was the “night song” of the starling, and I figured everybody knew about it.

This fall, I heard those crazy nocturnal sounds again, this time from atop the Boulder Bookstore in downtown Boulder. I recorded it and made spectrograms, and then I set off to the scientific literature to find out what kind of starling song it was.

It turned out nobody had ever recorded anything similar from a starling.

For a little while I started to get excited. Was I the first to realize that starlings’ night songs were different from their day songs? How could science have missed this? Starlings are abundant, they live in cities, they’re noisy as heck, and they’ve been studied like few other bird species! Was there a whole new starling repertoire being sung right under everybody’s noses?

You guessed it, I was being stupid. Tayler Brooks cleared up the confusion for me.

I was fooled by one of those electronic loudspeaker devices that they put on rooftops to scare away birds. According to the Bird-X Company, the BirdXPeller Pro “automatically broadcasts a variety of naturally recorded bird distress signals and predator calls to frighten, confuse, and disorient birds.” No wonder it sounded like a distressed starling…and then like a kestrel and a Cooper’s Hawk and a Red-shouldered Hawk. No wonder it was singing at night from the tops of buildings. Sigh.

I was fooled by one of those electronic loudspeaker devices that they put on rooftops to scare away birds. According to the Bird-X Company, the BirdXPeller Pro “automatically broadcasts a variety of naturally recorded bird distress signals and predator calls to frighten, confuse, and disorient birds.” No wonder it sounded like a distressed starling…and then like a kestrel and a Cooper’s Hawk and a Red-shouldered Hawk. No wonder it was singing at night from the tops of buildings. Sigh.

Now that we’ve had our little identification lesson for today, I want to ask this question of all the birders out there. Is the BirdXPeller Pro actually likely to work? According to the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, this type of repellent device is “only effective against the bird species whose distress calls are encoded on the microchip.” I find that difficult to square with Bird-X’s claim that the BirdXPeller Pro will repel not only starlings, grackles and sparrows, but also “seagulls,” cormorants, and, yes, vultures.

Frankly, I tend to think that most birds are smart enough not to be fooled by the same old playback over and over, even if it is a conspecific distress call. Then again, perhaps the Bird-X company is craftier than I’m giving them credit for. They’ve certainly sold a bunch of these devices, enough to warrant a caution to earbirders.

But…vultures?