Splitting the Gray Hawk

The Gray Hawk, whose scientific name recently changed from Asturina nitida to Buteo nitidus (AOU 2006), was historically considered two species:

- Gray Hawk (Asturina plagiata or Buteo plagiatus), comprising a single subspecies found from the southern United States south to northwestern Costa Rica;

- Gray-lined Hawk (Asturina nitida or Buteo nitidus), including races costaricensis, nitida[-us] and pallida[-us], ranging from southwestern Costa Rica south through much of South America to northern Argentina.

In recent years the AOU has recognized only a single species, with a range from Arizona all the way to Argentina, but evidence is mounting that it should in fact recognize two. The BNA account (Bibles et al. 2002, subscription required) mentions many well-established differences between the two groups in both plumage and measurements, which led B. A. Millsap to propose a split in his 1986 master’s thesis (abstract). Then, in 2003, Riesing et al. published a molecular phylogeny of the genus Buteo which not only found that Asturina was embedded within Buteo (resulting in the aforementioned change of genus) but also found evidence for a species split:

Substantial variability was detected within B. nitidus. The subspecies B. n. plagiatus is 9% apart from B. n. nitidus and B. jamaicensis costaricensis, respectively. Thus, the earlier proposed species status of plagiatus (Millsap, 1989) is supported by our data.

The American Ornithologists’ Union Checklist Committee, however, wasn’t convinced:

Riesing et al. (2003) suggested that the groups should be recognized as distinct species, but did not provide supporting data.

I’m no molecular biologist, so I can’t comment in depth on the quality of the data or the analysis, but I can say that Riesling et al. had a pretty small sample size: only a single sample each of the Gray Hawk subspecies nitidus, costaricensis, and plagiatus. And although they looked at two genetic markers overall, only one marker seems to have been sampled from all three taxa. In that one genetic marker, however, the samples of “Gray” and “Gray-lined” Hawks were as different from each other as the northern “Gray” Hawk is from Red-tailed Hawk, which is a substantial difference indeed.

Here is added evidence for the split: the plagiatus group and the nitidus group differ substantially in vocalizations, a fact that seems to have gone unreported in the literature so far. (Wikipedia says the vocalizations of both groups are identical, but does not cite this information.) In this post we’ll start simple:

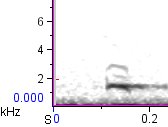

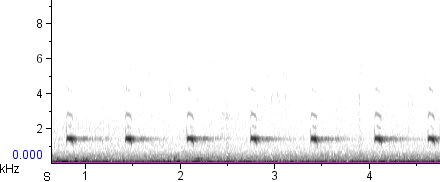

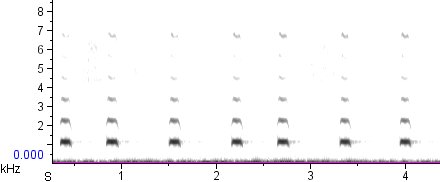

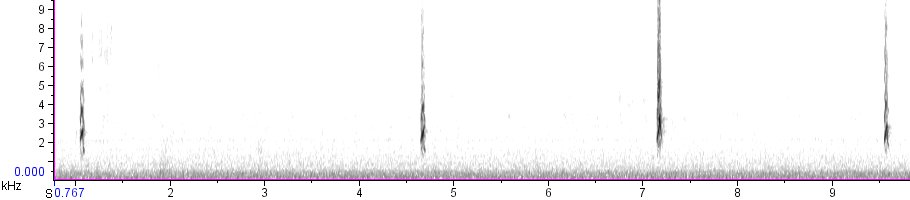

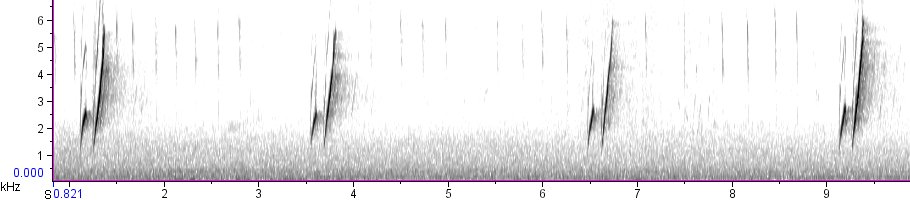

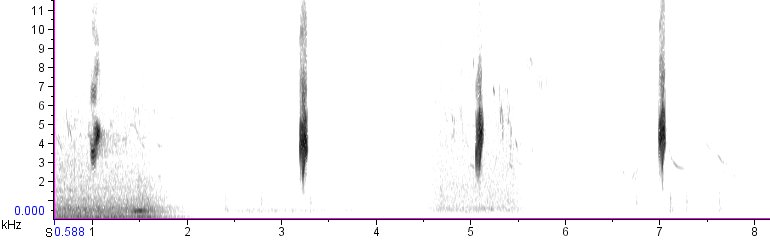

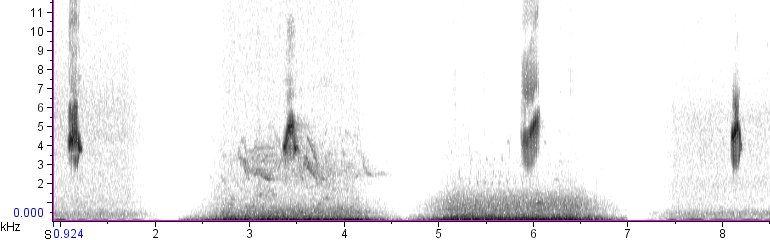

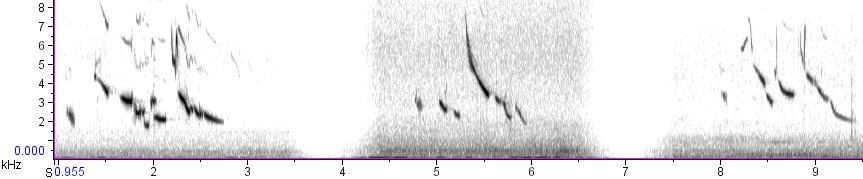

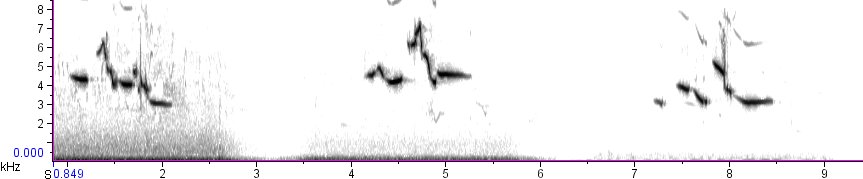

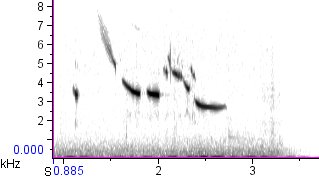

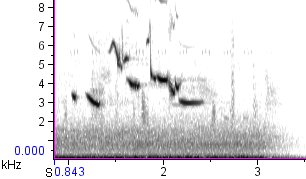

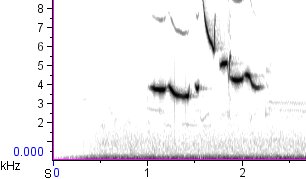

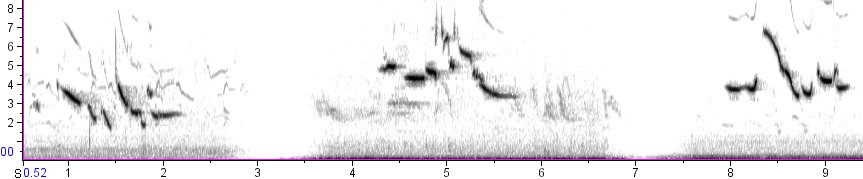

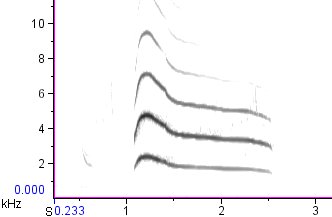

One-note (alarm) call

The most commonly heard vocalization of both species is the single-noted call, which apparently indicates alarm, at least in the plagiatus group. The single-noted call appears to be fairly stereotyped within populations, but strikingly different between them:

The following differences can be used to separate the two calls consistently:

- Duration. The call of the Gray Hawk lasts 1.5 – 2.0 sec, while the call of the Gray-lined Hawk is typically 0.5 – 1.0 sec long.

- Frequency. The call of the Gray-lined Hawk is significantly higher-pitched, with a maximum frequency of ca. 3.5 kHz, versus a maximum of less than 2.5 kHz for Gray Hawk.

- Energy spectrum. In the call of the Gray-lined Hawk, the energy is overwhelmingly concentrated in the fundamental, giving the call a clearer, more piercing tone quality, while in the call of the Gray Hawk, it’s the first harmonic that is strongest, with comparatively more energy in the second harmonic as well, relative to the fundamental. This gives the call of the Gray Hawk a distinctly more nasal tone quality.

- Pattern of inflection. The shape of the two calls on the spectrogram is consistently different. The Gray Hawk’s call is always a smooth overslur with a very early, very brief peak, with the final 75% of the call comprised of a long, nearly monotone “tail.” The Gray-lined Hawk, meanwhile, always shows a much more evenly overslurred shape, with a “flat-topped” look and a shorter and more sharply downslurred “tail.” In addition, the Gray-lined Hawk almost always has a “break” in its voice, a point in the terminal downslur at which the pitch drops almost instantaneously. In the above example this occurs almost exactly at the 1.5 sec mark.

On this page you will find comparative spectrograms from Xeno-Canto, with (as of this writing) 13 examples of Gray-lined Hawk’s alarm call and 2 examples of Gray Hawk’s. Xeno-Canto’s one recording from Panama, apparently the only representative of the Gray-lined subspecies costaricensis, seems odd, so a little more digging is in order there. Other than that, however, the distinctions I noted above hold in all cases, and I don’t note any systematic differences between subspecies nitidus and pallidus.

I’d like to revisit this issue in a future post, to investigate possible differences in the series call and to bring in results from the Macaulay Library‘s website, which appears to be under the weather at the moment. Stay tuned.