A Brief History of Spectrograms

1951 – 1995: The Sona-Graph Era

In 1951, the Kay Electric Co. produced the first commercially available machine for audio spectrographic analysis, which they marketed under the trademark “Sona-Graph.” The graphs produced by a Sona-Graph came to be called “Sonagrams.” For decades, all spectrograms were Sonagrams.

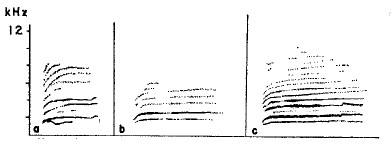

The original Sona-Graph had two settings, “narrow-band” and “wide-band.” The narrow-band setting was more accurate in terms of frequency, but less accurate in terms of time, and it tended to create spectrograms that looked rather anemic, like they had been drawn with a thin pencil:

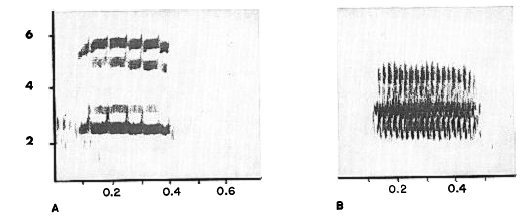

Here’s a classic Sonagram on the wide-band setting, which sacrificed frequency resolution for time resolution, making spectrograms look calligraphic, as though they had been drawn with a wide-bladed pen held vertically:

Note the discoloration of the spectrogram “boxes” above. It’s a reminder that the Sonagrams created by the original Sona-Graph were actual physical artifacts on paper. In this case Martin cut them out and pasted them onto another sheet of paper to create his figure, which was a common practice at the time.

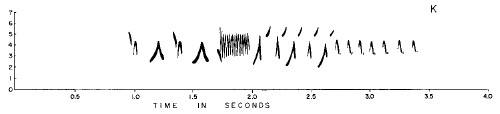

Another common practice was to cover the paper Sonagram with a sheet of acetate and trace the spectrogram with a pen to produce figures for publication. Many authors preferred this method because it created “cleaner” results — the pen eliminated background noise and equalized levels in the bird’s sound:

These traced spectrograms were some of the best that could be created in their time, but they were also in some ways insidious: they resulted in a simplification and sometimes a distortion of the sound, as human artistry made “prettier” what the Sona-Graph had rendered. I tend to think that many authors of the day actually traced the spectrograms they published even if they didn’t admit to it in their Methods section: for example, the spectrograms of Coutlee above look like they may well have been traced.

Logarithm Wars

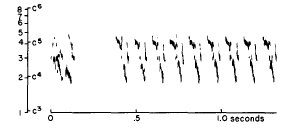

There were a few early attempts to publish spectrograms on a logarithmic frequency scale rather than a linear one, like this:

Marshall was rather militant about his unconventional y-axis:

Graphs of the calls were automatically scribed by the sonagraph machine. I have rendered tracings of them on a logarithmic frequency scale of musical octaves. This equalizes pitch intervals over the entire compass of the graph. For it is pitch and not frequency to which our hearing and that of the birds respond in nature, and for this reason the gross stretching apart of musical intervals in the upper part of the ordinary sonagram is absurd!

The “problem” that Marshall “solved” with his logarithmic axis is an actual phenomenon that we’ve seen before (albeit in a slightly different form): on a typical linear axis like those we use today, an octave takes up less vertical space near the bottom of the spectrogram than it does near the top. Perhaps because most scientists valued ease of measurement more than they valued ease of matching spectrograms to sounds (or, just as likely, because the Sona-Graph didn’t easily adapt to the logarithmic scale), Marshall lost this battle and the vast majority of all published spectrographs to date have maintained the linear frequency scale.

1967 – 1983: The Golden Age

A landmark in the history of American birding (and spectrograms), the Golden Field Guide to Birds of North America was the first (and to date only) major American field guide to include Sonagrams. This book, above all else, cemented the name and the notion of the “sonagram” in the consciousness of birders. Unfortunately, the spectrograms were widely considered something of a failed experiment. Stuart Keith’s otherwise mostly-positive review in the Wilson Bulletin (79:251-254) pretty much summed up the public reaction:

Another unique feature of the book is the use of sonagrams for depicting songs and calls. To my mind this is the least successful feature. While sonagrams have value in scientific studies of bird calls, their usefulness as an aid to field identification is very limited. To begin with, considerable practice is needed in order to be able to read sonagrams; but even when some proficiency is acquired, I doubt if anyone can really imagine or “hear” a new song simply by reading its sonagram. I challenge anyone who has never heard the call of a Red-bellied or a Gila woodpecker to “hear” the difference between their calls by reading the sonagrams on page 182. Admittedly it is interesting to see what a call which you already know looks like as a sonagram, but this is not the point. A field guide should teach you to have an idea of a song before you hear it. I maintain that you cannot learn bird songs from sonagrams.

I maintain that Stuart Keith was wrong on most of these points, and I hope this website will eventually prove it. I will grant him, though, that it was hard to learn bird songs from the spectrograms in the Golden Guide, which were half an inch tall and frequently quite illegible. Had they put more effort into the spectrograms in the field guides back then, who knows what earbirding powers modern birders might have by now?

1995 – present: The Digital Era

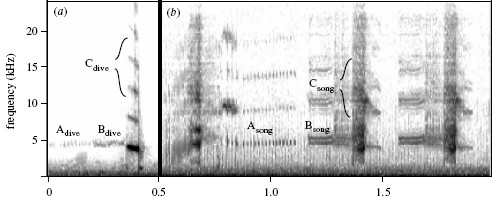

It wasn’t until the mid-1990’s that software finally displaced the Sona-Graph (albeit a fancier, updated version of it) as the audiospectrographic analysis tool of choice. Modern software continues to make spectrograms faster and more customizable: they can now be instantaneously adjusted to show finer gradations in the relative loudness of parts of the sound, using a grayscale digital display. Here’s an example of a spectrogram published recently by authors who really know how to use the modern equipment:

Unfortunately, some modern authors fail to use the modern equipment to its full potential, preferring instead to emulate the “old” black-and-white traced spectrograms. More on that later, in another post!