Do Evening Grosbeaks Sing?

A while back, I asked in a blog post whether Violet-green Swallows sing — and I answered that they do, because they produce complex repeating strings of stereotyped syllables, even if those syllables don’t sound like much to the human ear. Now it’s time to ask the same question of the poor, misunderstood Evening Grosbeak, whose vocalizations have often been vastly underappreciated, even by the authors of the BNA account:

Unlike most of their fellow oscines, Evening Grosbeaks do not make much use of the longer, more complex, learned vocalizations (i.e., songs) that characterize the vocal behavior of most songbirds. The Evening Grosbeak seems to be a songbird that doesn’t regularly use songs.

The BNA authors discuss the possibility of Evening Grosbeak song at some length, and by and large I think they do a thorough job of it. However, much of their analysis rests on a fundamental assumption that song in songbirds must be musical, preferably with trills and warbles attached — and as we’ve already seen many times, that just isn’t true. Not until the end of the article do they really strike pay dirt:

Some observers (L. Elliott pers. comm.; G. Budney pers. comm.) have recorded long series of flight calls, sometimes intermixed with trills, from Evening Grosbeaks. During these sequences, calls (or pairs of calls) are repeated rhythmically at intervals of about 1 s during bouts that can last as long as twenty minutes. Budney reports that long bouts are a regular occurrence at dawn in the Sierra Nevada of California. Perhaps these aggregated, rapid-fire calls act as the functional equivalent of songs during the dawn chorus.

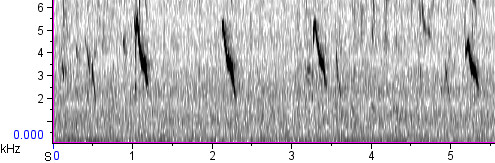

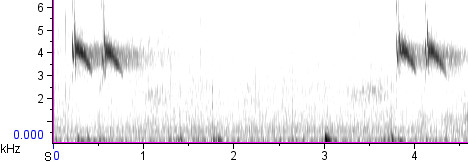

I too have heard song-like strings of flight calls from Evening Grosbeaks (for example, this bird), but I actually feel the best candidate for song in this species is its long strings of trill calls, not flight calls. In the spring of 2008, Evening Grosbeaks had come out of the higher elevations to invade a number of towns in southern Colorado, and when I stopped in the town of Norwood, I found the place infested with them (along with Pine Siskins and Cassin’s Finches galore). One male was sitting up atop a small aspen tree, broadcasting his trills to the world:

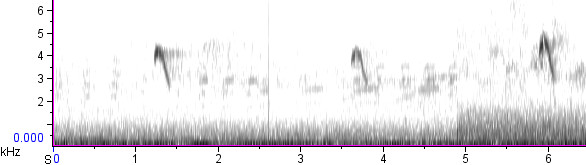

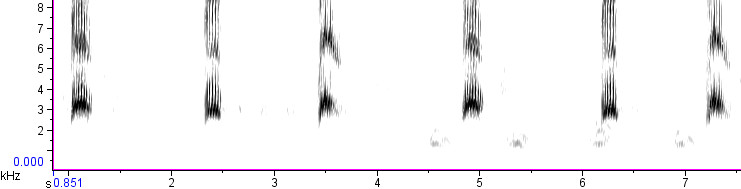

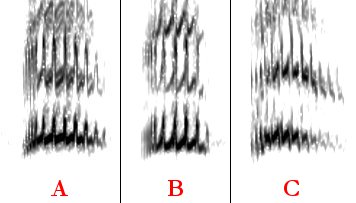

These trills are variable, but not randomly so. In fact, they sort into three well-defined types that we’ll call A, B, and C. They sound almost identical to the ear, but not quite; if you listen carefully, you can distinguish the order of the male’s calls on this 20-second cut: ABC, ABC, ABC, ABC, ACB, CAC. When we zoom the spectrogram in, we can see that the differences are subtle, but distinct:

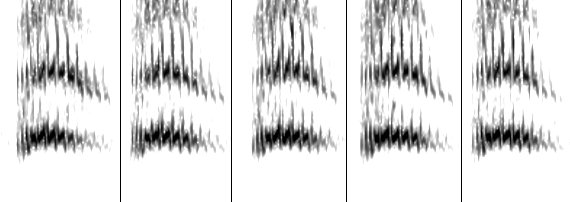

The “A” and “B” calls are quite similar at first glance, composed of backwards-L-shaped upslurs, while “C” is obviously distinctive, composed of zigzag backwards-N-shaped notes. The key distinction between “A” and “B” is that “A” is polyphonic, while “B” is not. It’s nearly impossible to determine this by looking at the fundamental (that is, the lowest and darkest of the three vertically stacked sounds on the spectrogram), but it becomes obvious when looking at the harmonics (the upper two versions) — the horizontal parts of the call are doubled in “A” and single in “B.”

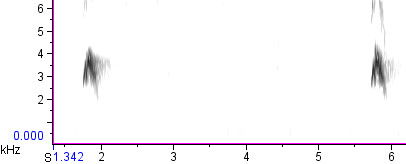

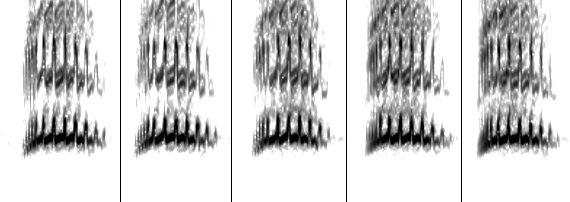

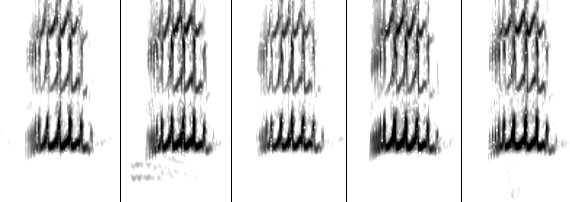

These differences are not random. All the “A,” “B,” and “C” calls are stereotyped — that is, they are perfect copies of one another, reproduced with exquisite precision. Compare the first five renditions of each call on the recording:

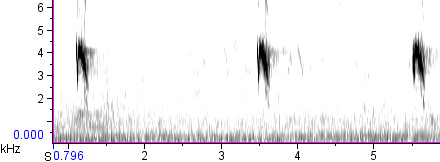

The Norwood bird isn’t the only Evening Grosbeak who’s been caught singing on tape. The Macaulay Library has a couple of recordings [1 2] of singing males recorded a few days apart in central Oregon by Thomas Sander. The first cut is rather brief, including only sixteen individual trills, but they too fit nicely into “A,” “B,” and “C” categories, much like those of the Norwood bird (click here to see a labeled spectrogram). The second cut is more extensive, and more impressive — for most of its first three minutes it features an apparently solo singer who incorporates six different trill types instead of three (labeled spectrogram here).

Obviously, more study of Evening Grosbeaks is needed to determine the actual function of these suspiciously song-like vocalizations, but I strongly suspect that they function as male advertising calls. Hopefully Aaron Haiman, who is currently studying Evening Grosbeaks, can get to the bottom of some of this!