Identifying Black-capped Gnatcatchers

Just 30 years ago, the dapper Black-capped Gnatcatcher was ultra-rare north of the Mexican border. Today it can be found with some regularity in decent numbers in several different locations in Arizona and New Mexico. But separating it from the more numerous Blue-gray Gnatcatchers can be a real challenge, especially in winter, when the males don’t sport their namesake caps.

Voice is a key field mark, but good descriptions and recordings of Black-capped Gnatcatcher vocalizations have until recently been in short supply, and confusion about the vocal differences between eastern and western Blue-gray Gnatcatchers has compounded the issue. Add Black-tailed Gnatcatcher to the mix, plus a dash of the genus-wide tendency to say unpredictable things, and you’ve got a recipe for confusion.

We’ll try to alleviate some of that confusion today.

Black-capped Gnatcatcher whines

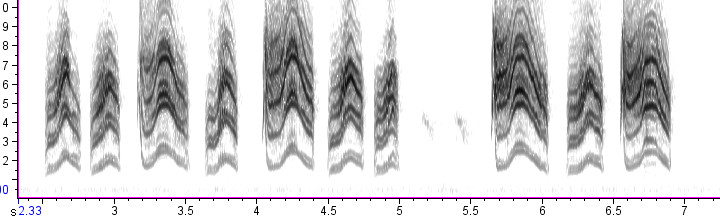

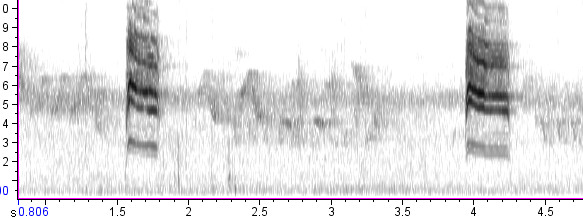

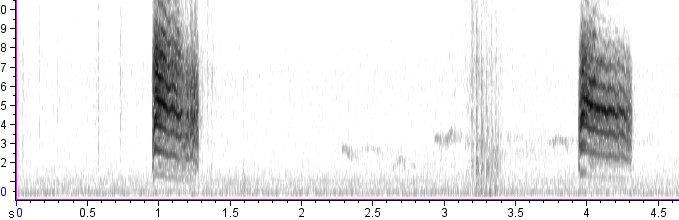

The single best way to identify a Black-capped Gnatcatcher is by listening for one of its most common calls, a distinctive polyphonic overslurred whine that reminds some people of a kitten’s meow:

This typical version of the call is strikingly similar to the distinctive mew of the California Gnatcatcher, but California is not found in the same regions as Black-capped. Of course, Black-capped calls are also variable. Here’s a rather odd version:

And here’s a downslurred variant:

(Here’s another downslurred example for good measure.)

Beware the Blue-grays!

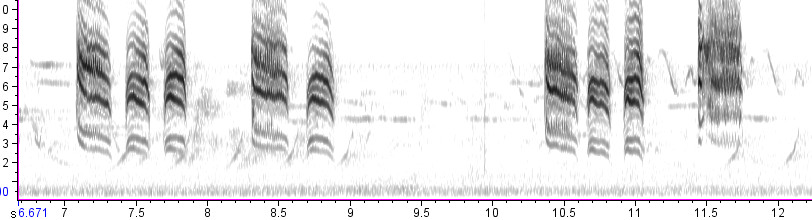

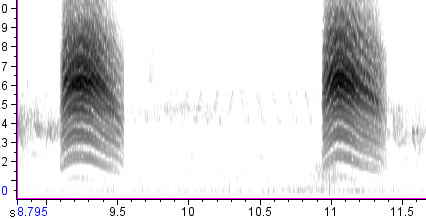

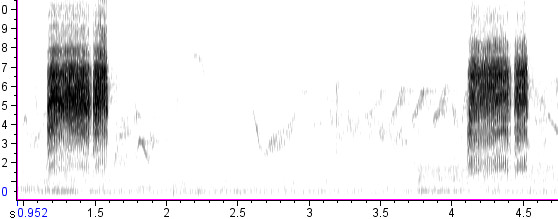

Not only is Blue-gray the gnatcatcher that looks most like Black-capped, it’s also the one that can sound most similar — especially the western population. As we saw in the last post, the simple song of western Blue-grays is composed of overslurred whiny notes. Usually the overslurred whines of Blue-grays are organized into short series during bouts of the “simple song,” while the similar notes of Black-capped are often (but not always) given singly.

When Black-cappeds give downslurred whines, they may be especially difficult to distinguish from the standard calls of western Blue-grays:

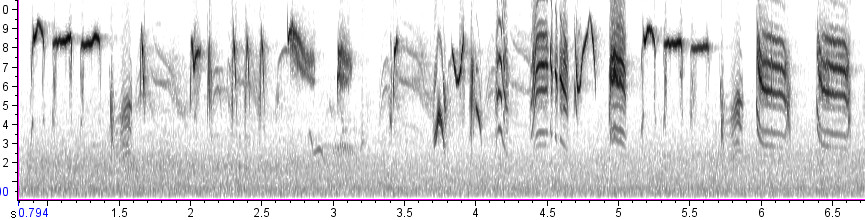

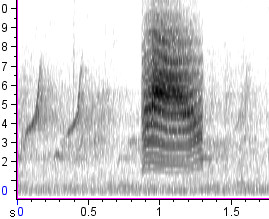

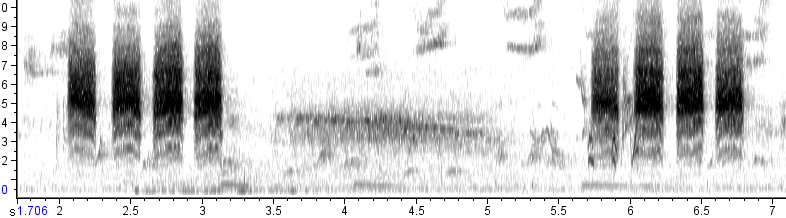

Black-capped Gnatcatcher rough calls

In addition to its trademark whines, Black-capped Gnatcatcher also gives some rough notes, possibly in alarm or as part of the simple song. These rough calls could be mistaken for the sounds of a Black-tailed Gnatcatcher.

Beware the Black-taileds!

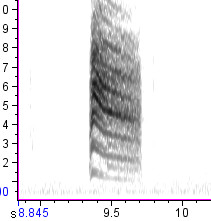

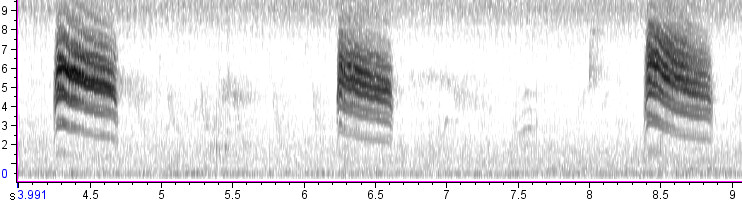

Among the western gnatcatchers, the Black-taileds are usually considered the ones with the most distinctive voices — rough, harsh, noisy, hoarse, unmusical, and rather unlike the higher-pitched, polyphonic, whiny voices of their congeners. But the rough calls of the Black-cappeds above encroach on traditional Black-tailed territory. The last call above, in fact, is virtually identical to some calls of Black-taileds, like this example:

Ultimately, we still know very little about the voice of Black-capped Gnatcatchers. They certainly sing a complex song like that of Blue-grays. They probably sing something like the simple song of that species as well, but what comprises that simple song isn’t clear — this recording may be an example of it. Rough notes appear to indicate agitation in at least some cases, but perhaps not always.

By far the best indicator of a Black-capped Gnatcatcher is the classic overslurred whine. My experience indicates that this call can be heard from about 80% of Black-capped Gnatcatchers within five minutes of observation. However, the species often gives variant calls for several minutes in a row, including downslurred or noisy versions that resemble those of the other two gnatcatcher species.

The take-home message? Though their “classic” call is distinctive, Black-capped Gnatcatchers are more vocally variable than many people have given them credit for. Identifying one in the field may require careful listening and a good deal of patience.