Eastern and Western Blue-gray Gnatcatchers

The Blue-gray Gnatcatcher sounds different in the West than it does in the East. As with geographic song differences in other birds, the differences in gnatcatcher songs might be of biological interest, perhaps encouraging the two groups not to mate with one another where their ranges meet. However, the differences in song are not well understood by most birders, nor particularly well described in most field guides. It doesn’t help matters at all that gnatcatchers are some of the most vocally complicated birds in North America. The longer one listens to them, the more confused one might get.

The Blue-gray Gnatcatcher is one of the very few North American birds whose western population has actually been better studied than the eastern population, at least when it comes to vocalizations. Most of what we know about the behavioral context of the different calls comes from a 1969 study by Richard Root that was conducted at the Hastings Natural History Reservation in Monterey County, California. Root’s observations suggest (and my own field experiences corroborate) that western Blue-gray Gnatcatchers have two basic kinds of song: a louder, simpler one used primarily in territorial advertisement, and a quieter, more complex one used primarily in close-range courtship. For today’s purposes, we’ll call them “simple song” and “complex song”.

Simple song

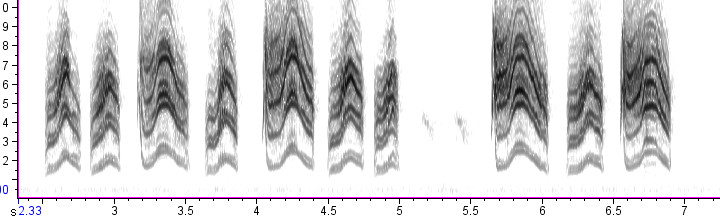

Here’s the simple song of western populations, which Root called the “advertising song”:

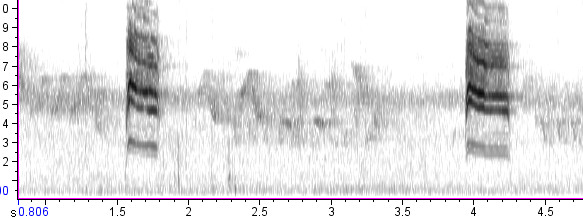

This is one of those magnificent spectrograms that deserves a moment of silent admiration. The irregular spacing of the dark and light partials is not only visually striking, but a sure sign of polyphony, the simultaneous use of both sides of the bird’s syrinx, making for the distinctive whiny (some say “wiry”) tone quality of the gnatcatcher’s song. This type of song is characterized by short series of 3-7 similar-but-not-identical notes, each one of which is typically overslurred. A slight tendency toward up-and-down squiggling inside the individual notes on the spectrogram speaks to the slight burry quality of the sound.

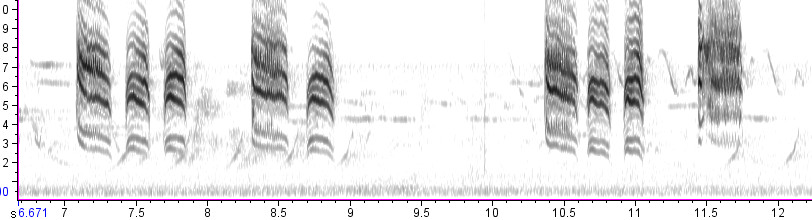

This “simple song” comes in many variations across the western half of the Blue-gray Gnatcatcher’s range, even within the repertoire of a single bird, but the example above is quite typical. Compare it with the simple song of eastern birds:

We still see the irregular stripey pattern that signals polyphony, but now only two dark partials dominate instead of three or four, and those two darkest partials are at a higher frequency and farther apart from one another than the partials in western songs. This translates into a higher pitch with a thinner, less nasal tone quality. And the tendency toward burriness is typically more pronounced, adding a grating quality to many notes that western birds most often lack. Note shape also differs, with eastern birds showing much less tendency toward the rollicking up-and-down patterns of western birds, but this mark is highly variable in both populations.

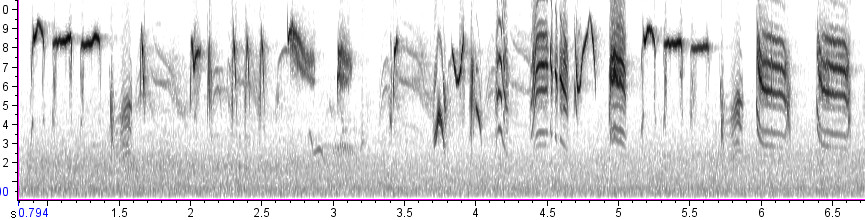

Complex song

Many people think of the complex song as the “true” song of gnatcatchers, probably because it better matches the traditional notion of a song as complicated and musical, but it is quieter and less frequent than simple song. Complex song is given by males in close-range courtship of females as well as some territorial boundary conflicts with other males. In both populations, the complex song is characterized by wildly diverse sounds, often including some mimicry, and herky-jerky rhythms that sometimes include a few repetitions of notes. The end result can sound something like a Brown Thrasher song played back at higher speed. But it’s usually easy to tell you’re listening to a gnatcatcher because of the liberal inclusion of individual whiny notes from the simple song. These notes, in fact, are the best way to tell whether you’re listening to the complex song of an eastern or a western gnatcatcher.

Note that there’s a complete range of intermediates between simple and complex songs in both eastern and western birds — the elements appear to mix freely, and a significant percentage of songs may be difficult to put into one category or the other.

Calls

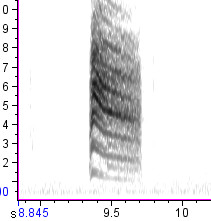

The word “call” gets used a lot to describe the simple song, but gnatcatchers do have non-song calls. The calls are similar in quality to notes of the simple song, and they may integrade with it, so that it’s often difficult to tell calls and simple songs apart. But here are a few examples of what I think are true calls:

As far as I can tell, the shape of the call note is pretty constant between populations and individuals: a nice even downslur. The differences in pitch and tone quality of eastern and western birds exactly mirror the differences between the simple songs — eastern birds are higher-pitched and less nasal, and possibly less noisy as well.

Overall, the differences in voice between eastern and western Blue-gray Gnatcatchers are subtle, but consistent, and experienced field observers or those with recording equipment should be able to identify the two populations in the field by voice, even if they are out of range. The breeding ranges of the two populations may meet or even overlap in west-central Texas or part of Oklahoma. All the birds I recorded in the Texas hill country (Bandera and Kerr Counties) were clearly eastern birds, while the ones in Big Bend were clearly western, but I’m not clear on where the boundary is or whether intermediates occur along it. I would love to get more information if anybody can share it!

2 thoughts on “Eastern and Western Blue-gray Gnatcatchers”

Great post, Nathan! I was just pondering gnatcatcher vocalizations today, upon hearing a Black-tailed Gnatcatcher pull off some pretty amazing mimicry of House Sparrows. It sounds like the complex song above from the eastern Blue-gray starts with mimicry of Black-capped Chickadee.

Comments are closed.