Identifying Eastern and Western Warbling Vireos

Warbling Vireo is among the many widespread North American species with east/west vocal forms that meet on the Great Plains. Along with other examples of this type of song diversity (Marsh Wren, Blue-gray Gnatcatcher), eastern (gilvus group) and western (swainsonii group) Warbling Vireos may represent two species, and if they are ever split, song would be the best way to identify them.

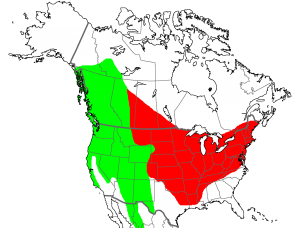

Look at a range map of Warbling Vireo and you’ll see that it continues in a pretty much unbroken swathe across North America. The eastern and western song types meet at the Great Plains/Rocky Mountains interface, and in at least some of those both occur in a fairly close proximity but remain identifiable to type. For example, Warbling Vireos singing on the eastern plains of Colorado not far from the foothills are typically of the eastern type, while those from the foothills west are of the western type. In the Black Hills of South Dakota eastern types occur in the lower elevations, and are replaced by westerns in the higher ones (Birds of South Dakota). What is not very well studied, however, is whether there is a cline in song types anywhere in their range, and how the birds react to each others’ song types in areas in/near potential overlap.

The plumage of the two forms is extremely similar. Western is often cited as having a darker crown and more defined eyeline, giving it less of the “blank-eyed” look associated with Warbling Vireo. It is also a bit whiter on the underparts and darker on the back, and the bill is slightly thicker (Birds of North America). However, these differences are very subtle, not well studied, and hard to see in the field. A much more reliable way to separate the types is by their primary song, which has consistent (if not always obvious) difference. I’ll first talk about the eastern song type, which many readers should be familiar with it, and then contrast the western form.

Eastern:

The song of the eastern Warbling Vireos is what gave the bird its name. It is a pleasant caroling song that rolls along, often ending in an emphatic higher note, transcribed at times as “if I could see it I would seize it and squeeze it til it squirts” or some variation thereof. The song phrases are typically around 2.5 to 3.5s long, and are made up of a series rich whistles that are slightly modulated. In the song of eastern Warbling Vireo, most of the initial notes are near the same pitch, with a few higher notes thrown in towards the end of the song. Below are a couple of examples of eastern song:

Western:

Western Warbling Vireo songs differ from that of eastern mostly in terms of pitch. Most western songs tend to have more high pitched notes, and these are placed more evenly throughout the song, breaking up the rhythm so that the whole strophe sounds less sing-songy than the song of Eastern. While the song of eastern gives the impression of a series of low, caroling notes, the song of western gives a jumbled and less structured feel, with an overall higher pitch. This difference in sound takes a little bit of practice to pick out, and there are some birds (especially in the contact zone?) that are harder to place as one or the other. A couple of samples of the western song type:

Where from here?

Despite the fact that the songs of these two types of Warbling Vireo are fairly well differentiated, very little is known about what goes on in the contact zones. This is where just about any birder visiting the western Great Plains and eastern Rocky Mountains can make a difference. Pay attention to the Warbling Vireos! Are they eastern, western, undefinable? There are very few recordings available from these areas, so anything you find will be interesting and useful.

2 thoughts on “Identifying Eastern and Western Warbling Vireos”

Andrew

Jon Barlow who I got to know at U of Toronto was the expert on this subject at the time. He had studied the overlap zone and mentioned to me that he had plenty of recordings and notes from the region they came together, and that they acted as species in that part of Alberta. After Jon passed away, with the help of Jim Rising and the Cornell folks we had his tape collection go to the Macauley Library of Nature Sounds. Perhaps some of the answers are in those tapes! Alvaro.

I have the iBird Pro phone app on my mobile phone. IBird Pro provides eastern and western version sound clips of Warbling Vireo. On recent trip to Colorado, at one mountain location, with a presumed western Warbling Vireo singing from Ponderosa Pines, I played the eastern version song. The songster immediately became interested and flew close and changed the speed of its song to match what was coming out of my mobile phone. Out at Tamarack Ranch in eastern Colorado, I played western Warbling Vireo songs to presumed eastern Warbling Vireos. Same thing, the local songsters slightly changed their tunes. What does this mean? Does it mean that perhaps Homo sapiens hears and reads more into song differences than Vireo gilvus does?

This song playback experiment should be tried by birders in other parts of the range of this potential split.

Comments are closed.