A Good Quiz

I recommend heading over to RMBO’s audio quiz before the 15th of November…their fourth installment is a good one. Easy to identify to genus, not quite as easy to peg the right species! Best of luck…

I recommend heading over to RMBO’s audio quiz before the 15th of November…their fourth installment is a good one. Easy to identify to genus, not quite as easy to peg the right species! Best of luck…

Well, the cycle is complete: Lesson Six on Polyphony is up. I’d love feedback from experts in audiospectrographic analysis in particular, because I may have messed up on some of the details this time around.

Of course, no sooner do I finish my lesson than I think of all the ways in which I could improve and expand it. I may work on that down the road. Meanwhile, the six-part series on this site will teach you basically everything you need to know about reading avian audio spectrograms. Enjoy!

While going through the Macaulay Library’s collection of Common Nighthawk vocalizations, I came upon something strange: a recording of what might be a hybrid Common x Antillean Nighthawk from south Florida.

Here’s some background. In the early sixties, Charles A. Sutherland studied the breeding biology of nighthawks on Key Largo, Florida. He made observations and audio recordings of both taxa breeding there: Chordeiles minor chapmani and the very different-sounding C. m. vicinus, which was not yet recognized as belonging to a separate species (and wouldn’t be until the early eighties, when the AOU would cite vocal differences and sympatric breeding in creating Chordeiles gundlachii, the Antillean Nighthawk).

Sutherland wrote up his findings in a 1963 article in Living Bird that remains perhaps the best source published to date on Common Nighthawk vocalizations. Unfortunately, he excluded the Antillean birds from his discussion. On the other hand, he did donate his recordings to Cornell, and now they can be heard online at the Macaulay Library’s website.

Sutherland’s recordings are noteworthy on many levels. For one thing, since he was in the area of sympatry, they often capture the calls of both nighthawk species at once. For another, Sutherland managed to record many rarely-heard vocalizations, such as begging calls of nestling Common Nighthawks, distraction displays by a female Antillean, and the “pik pik pik” notes given by Commons in aerial chases.

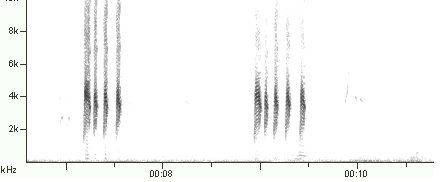

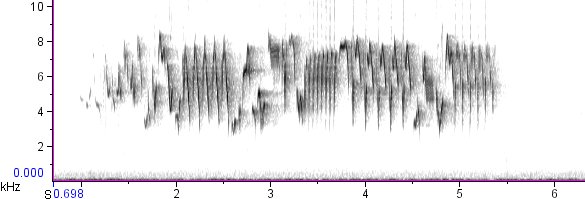

In the vocal notes on his recordings, Sutherland often referred to the Antillean Nighthawks as the “pi-ti-mi-dick” birds, after the distinctive rhythm of their calls. There is one individual, however, that he refers to as “the improper pit-i-mi-dick bird,” apparently because the thought its call didn’t sound quite right for an Antillean Nighthawk. You can hear this bird on Macaulay Library cut 5904. It used to be classified as a Common Nighthawk, but as of this writing Macaulay’s got it labeled as an Antillean, and it’s certainly a confusing bird. Here are a couple of spectrograms:

To listen to the bird, click here.

Note that the bird gives a mix of short “pik” notes (the vertical lines on the spectrogram) and Common Nighthawk-like “peent” notes (the thicker blotches). By themselves, both of these elements suggest Common Nighthawk, as that species gives both calls. However, what seems odd is that the “piks” and the “peents” usually seem to merge into one, “pik pik pikpeent,” so that the typical rhythm ends up echoing that of the stereotypical chicken vocalization: “buk buk bukKAW.” By going through every recording labeled “Common Nighthawk,” I located nine cuts that included the “pik” call [1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9], usually alongside the “peent,” but none of them contain anything like this combination rhythm.

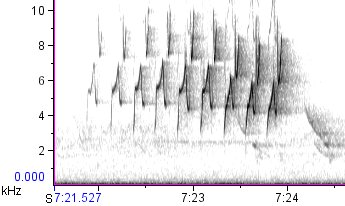

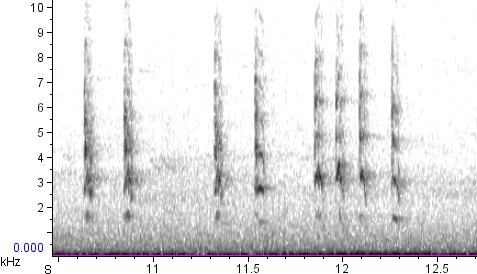

Here’s a typical Antillean Nighthawk call for comparison. It’s giving a relatively stereotyped “pit-i-mi-dick” of 2-6 notes in slightly decelerating series, the first element slightly longer than the others:

(click here to hear the bird)

As far as I know, Antillean Nighthawks do not give long series of individual “pik” notes like Common Nighthawks do, but I’d be interested to hear from anyone whose experience suggests otherwise.

As you can see, the “improper pit-i-mi-dick” bird is quite different from an Antillean. It may simply be a Common Nighthawk who is stumbling repeatedly over his words. But it sounds suspiciously odd to me, and given that it comes from the area of sympatry, a hybrid seems quite plausible. Interestingly, Sutherland mentions in his vocal notes that the call of this individual is not accompanied by the rapid flutter of wings that usually accompanies the primary call in both Common and Antillean Nighthawks. Who knows what significance that fact may have?

Comments?

They don’t call it the Golden Swamp Warbler anymore, but name would still be apt, because the flame-yellow Prothonotary is a familiar sight in the swampy areas of southeastern North America. It’s a wonderful and evocative bird, one that even non-birders tend to notice when it perches or sings nearby. It’s one of the few warblers that nests in cavities, and it is the sole member of the genus Protonotaria.

In 2006, I joined a volunteer team in Cornell’s search for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker in the White River National Wildlife Refuge of Arkansas. During the two weeks I spent walking around in the untrammeled, uncampephiled wilderness, I had many spectacular close-up encounters with wildlife, but the most amazing was with a male Prothonotary Warbler. I was standing in hardwoods on the edge of a flooded swamp when the golden bird popped up over the water and began to sing. I switched on my microphone to record it, and suddenly it flew into a leafless sapling right over my head. I didn’t dare breath or move; I just kept the microphone running, hoping the bird would stay in the tree, hoping it would sing again. Sure enough, after a few minutes of foraging it began to belt out its familiar primary song: a fast monotone series of high clear upslurred whistles, not particularly musical, often transcribed as “sweet sweet sweet sweet sweet.”

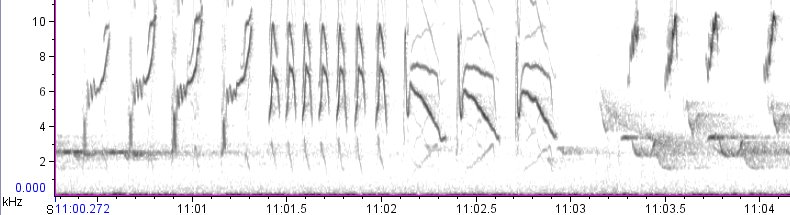

But then the bird did something even more extraordinary. It began to sing another song, one that was so faint that if the bird hadn’t been within five meters of me, I surely wouldn’t have heard it. And it was like nothing I’d ever heard from a Prothonotary before:

I went to the literature to find out what I had recorded, and discovered this in Lisa J. Petit’s Birds of North America account (emphasis mine):

Second, less frequent song is sung primarily during interactions with females, often in aerial Flight Display. This extended song (Spector 1992) is longer and slightly more complex than primary song, beginning rapidly and slowing down at end: chwee-chwee-chwee- chwee, teer, teer, teer (LJP) or che-wee-che-wee-chee-chee, chee-chee-che-wee-che-wee (Walkinshaw 1979). Brewster (1878) described this song as resembling song of Canary (Serinus canaria), sung quietly, and consisting of “trills or water-notes interspersed.” Roberts (1899) referred to the song as beginning with the “usual rapid monotone” and ending with a “varied warble.” No sonograms of this song are known to exist.

“No sonograms known to exist,” of course, is the same thing as saying “no recordings known to exist.” Well, we fixed that, didn’t we?

Or did we? Upon reflection, the quote above demonstrates some of the difficulties inherent in trying to match old voice descriptions with modern recordings. Is this really the “alternate” song of males? After all, no female was present, and the bird wasn’t singing in flight. Could it be some other type of song? In her account, Petit also mentions two other potential candidate vocalizations, apparent juvenile subsong and female song:

Two separate observations by LJP during Jul 1985 of immature birds (sexes unknown, both in femalelike plumage-one color-banded, 45 d old; the other unbanded, assumed immature on basis of behavioral interactions with adult pair) singing quiet, raspy, oriolelike warble that did not resemble primary song of adults. Songs were 2-3 s long and were repeated 3-4 times. In Jun 1987, an unbanded female (apparently adult, since it was building nest) was heard to give same type of song, repeated 3 times.

I’m not sure how female song fits into the picture, or whether some of the observers cited in the first quote might have been describing it, but one thing is clear: What I recorded was not subsong. Subsong is given by juvenile birds between fall and spring as they practice for their big debut on a breeding territory. It’s poorly structured, with individual notes randomly mixed and rarely repeated, or repeated in garbled form. The song I recorded, on the other hand, was crystallized: the bird repeated it more than a dozen times, and each time it followed the exact same syntax pattern, with small variations in the exact number of notes A, B, and C, but absolutely no variation in their order, fine structure, or rate of delivery.

Many warblers have complex alternate songs. Some better-known examples include the “flight songs” of Ovenbird and Common Yellowthroat (for the latter, listen here, between the 21 and 24 second marks). Paul Driver’s got a neat recording of the extended song of Worm-eating Warbler, and Andrew Spencer has posted to Xeno-Canto what may be an alternate song of Black-and-White Warbler, although it may also be a type of call. Many of these song types are rarely heard and even more rarely recorded, so I’d love to hear of more examples.

Given that Prothonotary Warbler has attracted a good deal of research attention over the years, I would be surprised if nobody else had recorded the alternate song by now. If you have any information to share, please let me know. It’s probably worth writing up a note for publication in a journal.

I’ve finally posted Lesson Five on Nasality. It’s a bit of a doozy, but I’m proud of it, especially since it’s getting into some territory that nobody’s really published on before, at least vis-a-vis psychoacoustics, since Peter Marler’s classic 1969 article “Tonal Quality of Bird Sounds“.

For that reason, and because I’m afraid I may have made it a little overly complex, I’m particularly interested in getting feedback on this page. Let me know how it treats you. One more installment is planned after this one, on polyphony…and then we’ll have covered it all!

I have a confession to make.

For six years now, after my morning commute, I have parked below Folsom Field, the football stadium of the University of Colorado, and walked around the edge of it on my way to my office. Frequently, I used to hear this odd bird singing from somewhere up on or near the roof of the stadium:

I could never see the bird; it always sounded echoey, like it was inside the roof of the building. Sometimes it would sing in the mornings, but more often it would sing at night — sometimes all night, as far as I could tell. Fall, winter, spring, no matter: the unseen singer was belting it out.

The bird sang in bouts consisting of series of notes; it had at least eight different note types, many of which sounded screechy, and some of which were dead on for European Starling. Some of its note types sounded like mimicry — of birds like American Kestrel, Cooper’s Hawk, and Red-shouldered Hawk — which also pointed to starling, as did the singer’s habitat (the roof of a building in a predominately urban environment) and its insomnia.

So I just figured it was the “night song” of the starling, and I figured everybody knew about it.

This fall, I heard those crazy nocturnal sounds again, this time from atop the Boulder Bookstore in downtown Boulder. I recorded it and made spectrograms, and then I set off to the scientific literature to find out what kind of starling song it was.

It turned out nobody had ever recorded anything similar from a starling.

For a little while I started to get excited. Was I the first to realize that starlings’ night songs were different from their day songs? How could science have missed this? Starlings are abundant, they live in cities, they’re noisy as heck, and they’ve been studied like few other bird species! Was there a whole new starling repertoire being sung right under everybody’s noses?

You guessed it, I was being stupid. Tayler Brooks cleared up the confusion for me.

I was fooled by one of those electronic loudspeaker devices that they put on rooftops to scare away birds. According to the Bird-X Company, the BirdXPeller Pro “automatically broadcasts a variety of naturally recorded bird distress signals and predator calls to frighten, confuse, and disorient birds.” No wonder it sounded like a distressed starling…and then like a kestrel and a Cooper’s Hawk and a Red-shouldered Hawk. No wonder it was singing at night from the tops of buildings. Sigh.

I was fooled by one of those electronic loudspeaker devices that they put on rooftops to scare away birds. According to the Bird-X Company, the BirdXPeller Pro “automatically broadcasts a variety of naturally recorded bird distress signals and predator calls to frighten, confuse, and disorient birds.” No wonder it sounded like a distressed starling…and then like a kestrel and a Cooper’s Hawk and a Red-shouldered Hawk. No wonder it was singing at night from the tops of buildings. Sigh.

Now that we’ve had our little identification lesson for today, I want to ask this question of all the birders out there. Is the BirdXPeller Pro actually likely to work? According to the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, this type of repellent device is “only effective against the bird species whose distress calls are encoded on the microchip.” I find that difficult to square with Bird-X’s claim that the BirdXPeller Pro will repel not only starlings, grackles and sparrows, but also “seagulls,” cormorants, and, yes, vultures.

Frankly, I tend to think that most birds are smart enough not to be fooled by the same old playback over and over, even if it is a conspecific distress call. Then again, perhaps the Bird-X company is craftier than I’m giving them credit for. They’ve certainly sold a bunch of these devices, enough to warrant a caution to earbirders.

But…vultures?

It was a wet and foggy day in April. I was standing in a damp little nook in dense woods, long before the first leaves would even think about opening, weeks before most migrating birds would get within a thousand miles of southeast South Dakota, listening to a cascade of musical notes that seemed like it would never end. It was echoing off the trees and the mossy banks, coming from somewhere tantalizingly close — but from exactly where, I couldn’t for the life of me figure out. After I stood there for perhaps ten minutes, I finally spotted it: a tiny brown bird singing from a pile of leafless brush, fifteen feet in front of me in plain sight. My first Winter Wren.

By some strange coincidence, the details of that experience almost perfectly match the details of my first encounter with Pacific Wren, when, on another wet and foggy day in April, I spent another ten minutes trying to find the amazing vocalist hidden among the dense, damp vegetation, this time on the slopes of Skinner Butte in Eugene, Oregon. At the time I had little idea I was seeing a different bird than the one I knew from the east. The song was familiar, or so I thought — unmistakable, really.

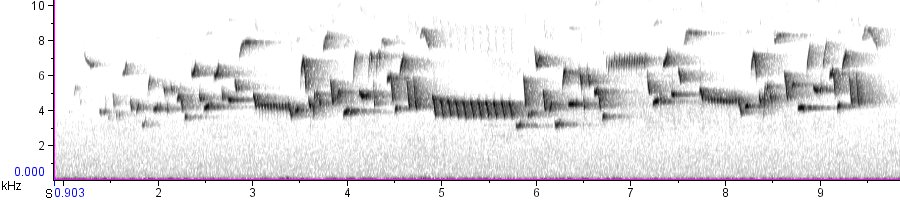

To this day, in the field, I have some difficulty separating the songs of the two forms (which may be separate species soon, for those of you just tuning in). Both are remarkable vocalists, with long-running musical strings of jumbled high-pitched notes and trills:

It’s not as easy as separating them by call, but with practice, Winter and Pacific Wrens are usually distinguishable by song. Here are some points to consider:

A good way to think of the difference in tone quality is to listen for the trills inside the wren songs and compare them in your head to the the “classic” song of Dark-eyed Junco and the “classic” song of Chipping Sparrow (which are, of course, themselves often difficult to separate by ear). The Winter Wren tends to have the more musical, junco-like trills, while the Pacific Wren often trends towards an unmusical, Chipping Sparrow-like (or even Brewer’s Sparrow-like) lisping rattle.

Song delivery also differs, although this can be difficult to ascertain unless you have a great auditory memory. Winter Wren males have only a few stereotyped songs in their repertoire; successive strophes of song are almost always identical. Pacific Wren males sing with far more songtypes, and they also recombine their songs — the beginning notes of successive strophes are frequently identical, but the endings vary widely.

For more practice, and to hear some more of these fantastic bird songs, head over to Xeno Canto’s Winter/Pacific Wren collection.

The American Ornithologists’ Union Checklist Committee recently updated its slate of taxonomic proposals. Lots of exciting stuff here, including proposed species status for our old friend, the South Hills Crossbill, and a split of Western Scrub-Jay. The proposed split I want to focus on today, though, is one that’s long in coming, and quite likely to pass, in my opinion: the split of Winter Wren into eastern and western North American species.

Why split the Winter Wren? For starters, eastern and western populations are 8.8% divergent in their mitochondrial DNA. (Trust me, that’s a lot.) Songs and calls differ diagnosably. Furthermore, the two forms nest side-by-side in the northern Canadian Rockies without interbreeding. Analysis of vocalizations and genetics haven’t turned up anything that really looks like a hybrid. Really, this looks like a pretty straightforward split, even by the “old” biological species criteria.

So, it looks like come next summer, we’ll probably have a new taxonomy in the genus:

How do you tell the two apart by sound? For today, we’ll look at the calls, which is the easiest way to identify them, especially in winter.

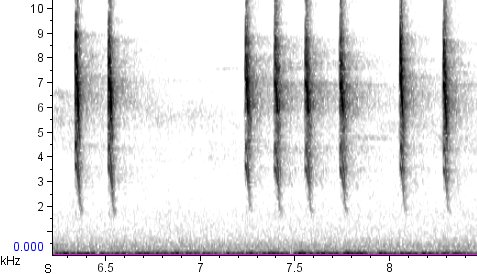

With direct comparison of soundtracks and spectrograms, the differences are obvious. The Winter Wren’s call is much clearer, with discrete harmonic bands; both spectrographically and aurally it is reminiscent of the call of Song Sparrow. The Pacific Wren, by contrast, has a call that is much noisier and higher-pitched, and, on average, slightly briefer. It is often compared to the call of Wilson’s Warbler. Although the call may not look higher-pitched on the spectrogram (since the minimum and maximum frequencies of both calls are about the same), note that the darkest part of the Pacific Wren spectrogram (and therefore the loudest part of the call) tends to concentrate around 6-7 kHz, while the darkest part of the Winter Wren spectrogram comes in at about half that. This accounts for the perceptual difference in pitch.

In my next post I’ll look at how to tell these two species apart by song. As these two are both fantastic singers, it will be a melodious post indeed!

The second installment in our occasional profile series spotlights Tayler Brooks of Brier, Washington, a newly active young recordist who was one of the expert sound ID panelists at the recent Western Field Ornithologists conference in Boise. Tayler grew up in western Washington and became interested in birds at the age of 12. For the past three years, bird sounds have been her favorite bird-related area of study. She has just started her second year in college, studying biology; she is very involved with various projects of the Puget Sound Bird Observatory and is a volunteer for her local Audubon chapter.

Here’s the equipment that Tayler uses:

Tayler had this to say about how she uses her equipment, and why:

With my growing interest in better understanding bird sounds, I now almost always take my recording equipment into the field with me whenever I’ll have a decent change at being around birds that are making noise. Like binoculars, it has become one of those things that feels strange to leave the house without when I’m bound for places in nature. One thing I’m always looking for when I record is capturing variation be it within species or populations, so I can be more familiar with the lesser known sounds of even common species. That in particular opened up a new world of discovery for me when I really started to take a closer look at the more complete set of sound a given bird species makes. Also, recording vocalizations from species groups not well represented, such as many types of waterbirds (gulls, ducks, and non-breeding calls of shorebirds) I also find exciting.

I asked her if she had any tips for beginners, and she responded:

Go recording solo or with small groups of people. This may seem obvious, but I thought I’d mention it since I often go out in search of birds with a group of five or so. The smaller the group (in many cases), the more you’ll be able to hear, and making cleaner recordings that require less editing is all the more easy.

Also, give recording in mono a try. It’ll save you a lot of memory space.

Tayler has contributed many fine recordings to Xeno-Canto. She particularly recommends this Red-eyed Vireo recording and this Winter Wren. Enjoy!

Here’s another quiz sound from Boise. Can you identify it?

Isn’t that the world’s most fantastic sound? And talk about distinctive. The panelists asked me if it was even a bird. 🙂 Yes, it’s a bird, and I recorded it in Orange County, California, in March 2009. Here are a couple more wonderful noises from the same species:

The bird is Red-crowned Parrot (Amazona viridigenalis), and as I quickly discovered when I arrived at Santiago Oaks Regional Park for a morning of recording, its bizarre and stentorian voice has become one of the characteristic sounds of suburban Orange County. On the freeway that morning I had seen large flocks of parrots coming off of night roosts, but I wasn’t able to identify them. In fact, I didn’t know which species of parrot I was dealing with at Santiago Oaks until well after I got home. My first tentative identification in the field was Lilac-crowned Parrot (Amazona finschi). Red-crowneds and Lilac-crowneds look surprisingly alike, and I didn’t have a way to compare their calls.

Why not? Because like other exotic species, parrots are woefully underrepresented in commercial bird sound publications. Bird Songs of California by Geoff Keller doesn’t include any parrots. The Stokes Field Guide to Bird Songs (Western Region) has the Red-crowned, by dint of its establishment in South Texas, but it doesn’t have the Lilac-crowned. Nor any of the other thirteen parrot species that have “established naturalized populations” in California per the California Parrot Project.

Partly, of course, exotic birds are underrepresented in sound collections because they have traditionally been underrepresented in field guides and checklists. Before making a species “official,” state records committees and the AOU and ABA checklist committees want to be certain the birds have established enough of a population to ensure their long-term survival in their adopted land. And that’s valuable information.

In the meantime, however, whether their immigration status is legal or not, the exotic birds are unquestionably here, and they are unquestionably making noise. And that presents us with a great opportunity — first, to learn the voices of the newest members of our local avian soundscape — and second, to get recordings, sometimes right in our own backyard, of species that might be rare, little-known, and hard to encounter in their native range.

But wait. Are the recordings of exotic birds “legitimate”? “Authentic”? Are they going to sound the same as they do where they came from?

Well, that depends. If the species is one with an innate song, then the answer is almost certainly yes. The millions of Eurasian Collared-Doves in this country sound very much like the millions in Europe and Asia, because collared-doves don’t learn their songs; they inherit them genetically. Some birds do learn their songs, however, and those songs may well change, especially over time, if the soundscape changes around them. Most birds with learned songs are apparently genetically predisposed to pick out the sounds of their own species from the chorus and imitate those, but if they’re first- or second-generation immigrants in an avian Babel, they might not have many, or any, of their own species to learn from. Might the scarcity of conspecific tutors restrict the repertoire size of immigrants? Might it force them to innovate or imitate other species?

We don’t really know. And that’s one of the main reasons why exotics are worth recording. We could learn a lot about the cultural transmission of song by recording, say, Red-whiskered Bulbuls in Florida or California. We could learn a lot about the biological components of song by recording hybrid birds, which may be more frequent among exotics. We could learn a lot about what these birds sound like in their native ranges without having to travel there ourselves. Even the “lowly” House Sparrow might have a lot to teach us, if we set out to discover whether regional dialects have begun to appear in North America since the species first landed here in 1852.

So it’s time for another call to action from me. Record exotic birds. Record starlings, collared-doves, House Sparrows, House Finches, Ring-necked Pheasants, Common Mynas, partridges, parrots, and pigeons, because they’re slipping under the radar and they have a lot to teach us. In common parlance, “exotic” is the opposite of “boring,” and I think that’s the way it should be with birds as well.