Curve-billed Thrasher Identification

The AOU checklist committee recently rejected a proposal to split the Curve-billed Thrasher into two species: the “Palmer’s” Thrasher (palmeri group) in Arizona and West Mexico, and the nominate or “Eastern” Curve-billed Thrasher (curvirostre group) in the rest of the bird’s range.

Although very similar, the two groups can usually be distinguished by sight. In the photos above, note that the eastern bird (right) has a much whiter background color to the breast, resulting in stronger contrast with the breast spots; it also shows sharper and bolder white highlights in the wings and tail. The stronger throat pattern, with a more distinct dark line bordering the white throat, may also be significant. However, the much colder, grayer tone to the plumage overall is likely an artifact of photo lighting.

Interestingly, one of the committee members who voted “yes” on the split did so in large part because of differences in the call notes between the two forms, which I hadn’t seen discussed anywhere before:

YES. I now favor splitting palmeri – the clincher for me is that palmeri has distinct call note differences, a clear upslurred whit-wheet, as opposed to a two note whit-whit in which both notes are the same.

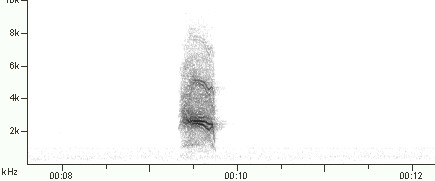

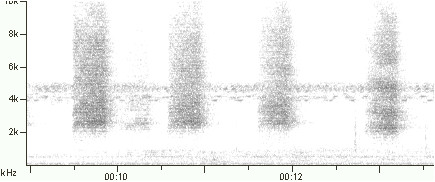

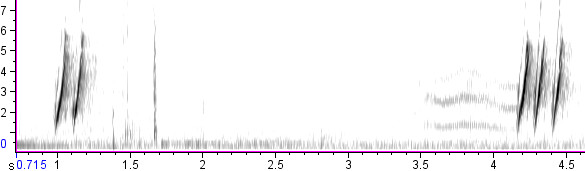

I have investigated this difference, and it seems to hold up across (at least) most of the species’ US range. The vast majority of the call recordings I could find from well inside the range of “Palmer’s” Thrasher showed the same typical pattern: two upslurred whistles that started at the same pitch, with the second one ending much higher:

Whereas the call of eastern curvirostre-group Curve-billed Thrashers consist of nearly identical notes, both upslurred across a wide frequency range like the second note of the “Palmer’s” call:

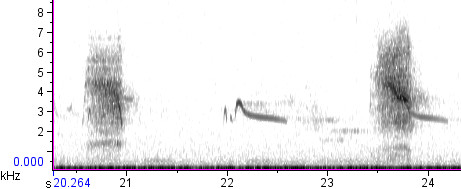

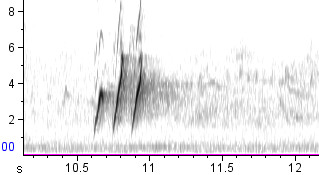

Both groups of Curve-billed Thrashers give versions of this call with 3 or more notes, particularly when they are excited. When the eastern curvirostre group does so, as you can see in the spectrogram above, all the notes tend to be similar. When western palmeri birds extend their calls, the first note is usually of the stunted variety. The third note (and any subsequent notes) tend to be like the second, but a little softer, so that the second note ends up getting the emphasis: “wit-WEET-weet”:

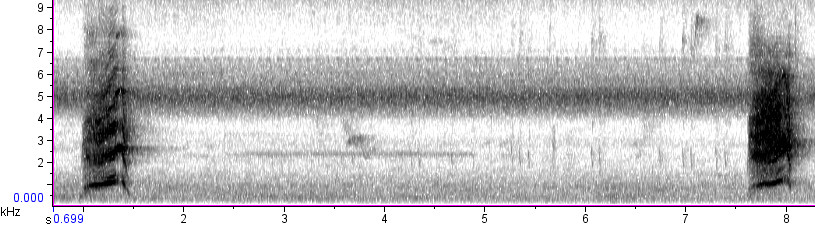

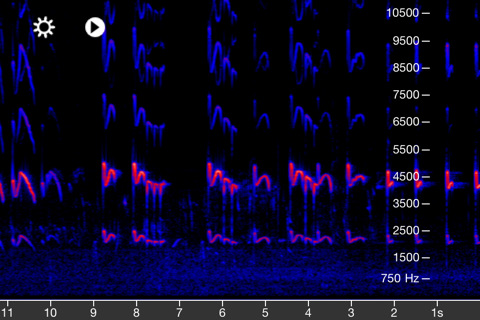

Some Curve-billed Thrashers in southeast Arizona give multi-note calls that are difficult to classify. Here’s a bird from a few miles south of Eloy in Pinal County, where I believe the palmeri subspecies would be expected:

Here’s some more from the same individual bird:

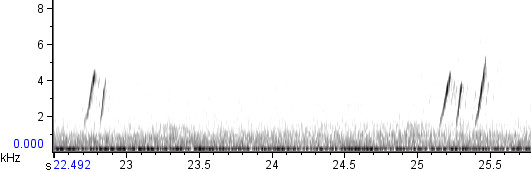

The two-note versions of this individual’s call tend to seem like the reverse of the typical palmeri pattern, with the second note quieter and less extensively upslurred than the others. One might suppose this could be an intermediate bird, since the palmeri and curvirostre groups apparently overlap in southeast Arizona, but most educated guesses that I’ve seen have placed the overlap zone farther east, between Tucson and the New Mexico border. I don’t believe this bird was identified visually to subspecies, so it remains a question mark for now.

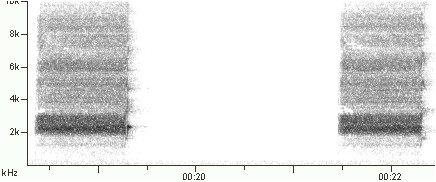

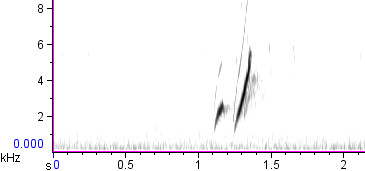

Just to whet the appetite of the curious, here’s a Curve-billed Thrasher call from the Oaxaca valley in southern Mexico, which preliminary DNA studies showed as being distinct from either the palmeri or the curvirostre group (though apparently more closely allied with the latter). Note again the “WEET-wit” pattern, which is the reverse of palmeri’s:

Obviously, more sampling is needed to fill in the many gaps in our knowledge of the Curve-billed Thrasher and its vocal variation. Amateur recordists of the southwestern US and Mexico, this is your cue.