“Least” Bell’s Vireo

I’ve always been mystified by the breeding range of Bell’s Vireo. It inhabits three seemingly very different places — the dense deciduous tangles of the Great Plains, the mesquite thornscrub of southeastern Arizona, and the riparian chaparral of southern coastal California. Sure, they’ve all got lots of dense thickets, but so do lots of places in between.

As far as I can determine, the only other birds that occupy Bell’s Vireo’s entire range are continent-crawling generalists like House Finch and Mourning Dove that can be found practically everywhere. How can Bell’s Vireo be so forgiving of the differences between, say, a streamside plum thicket in South Dakota and a tangle of mesquite in the Arizona desert, without being able to tolerate the deciduous scrub of the Colorado foothills?

Part of the answer, of course, is that each of these habitats boasts a unique population of Bell’s Vireo with unique habitat preferences. Great Plains birds are the yellowish, greenish nominate subspecies; Arizona is home to the much less colorful subspecies arizonae; and coastal California hosts the endangered “Least” Bell’s Vireo,V. b. pusillus, the grayest of them all.

Recently, Elisabeth Ammon of the Great Basin Bird Observatory asked me for help in determining whether there are any vocal differences between pusillus and arizonae. During the upcoming breeding season, GBBO will be surveying sites in Death Valley National Park for Bell’s Vireo, including an area where the species was found last summer. If it is found to breed in Death Valley, the national park’s management plan may depend on whether the birds are determined to be of the federally endangered “Least” subspecies or the commoner arizonae.

The Sibley Guide to Birds says no vocal differences are known between the subspecies, but the recently revised Birds of North America account suggests otherwise:

Geographic Variation

Little known. A comparison of the samples taken from California and Arizona show slight differences in repertoire size, song length and number of notes per song…. Field researchers subjectively report qualitative differences in songs in different regions.

Unfortunately, BNA’s claims of vocal differences are backed up by very little quantitative information — only the observation that “Least” Bell’s Vireo has an average repertoire size of 9.2 songtypes per bird, whereas arizonae averages 10.6 songtypes. That’s a small difference indeed, one that means the repertoire sizes must necessarily overlap, and one that could even fall entirely within the margin of error. Even if further investigation confirms this average difference, it would be of zero use in field identification. And BNA says nothing further about differences in song length and number of notes per song. Thus, we’re left to investigate the most slippery category:

Qualitative differences

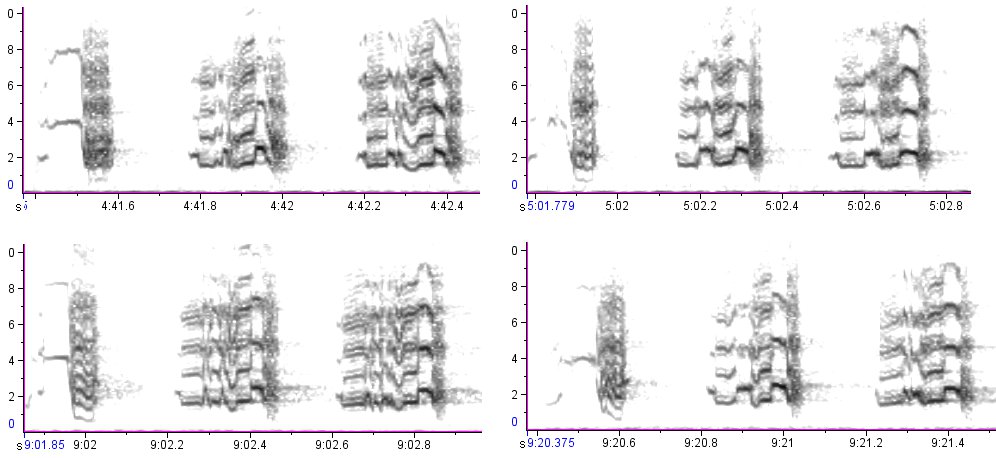

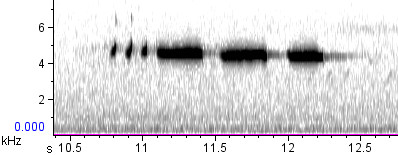

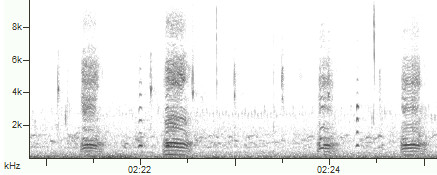

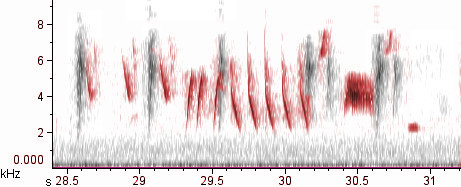

The initial prognosis for this blog post was grim, since the “Big Three” internet repositories of bird sounds – the Macaulay Library, the Borror Lab, and Xeno-Canto – contain precious few recordings of “Least” Bell’s Vireo. As of this writing, Macaulay and Borror lack them completely, and XC has only a few, all from Baja California Norte:

(There are two more possible Leasts on XC, from Baja California Sur and the Yolo Bypass in California, but I couldn’t confirm the subspecies in either case.)

YouTube to the rescue

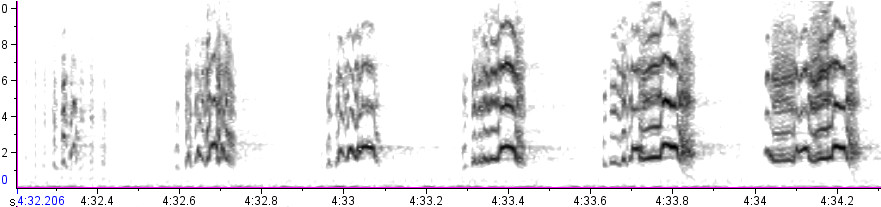

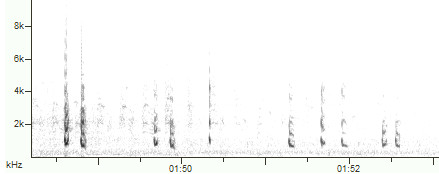

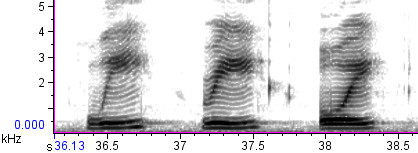

Strange as it may seem, at the moment, YouTube actually contains more minutes of “Least” Bell’s Vireo song than the “Big Three” audio websites combined. Here are three definite “Leasts” (YouTube has at least one other possible/probable Least as well):

- Update 4/2/2011: Matt Medler informs me that Macaulay actually does have several recordings of “Least” Bell’s Vireo [1 2 3 4 5]! For some reason they were not originally visible to mortal eyes, but Matt has worked his magic, and now they appear when one searches the archive with the common name (“Bell’s Vireo”).

“Arizona” Bell’s Vireo

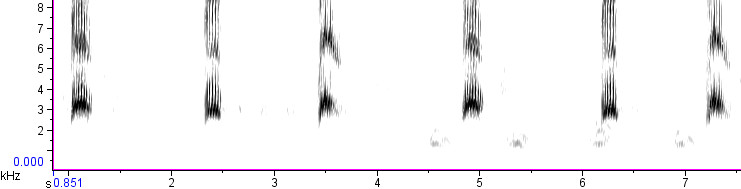

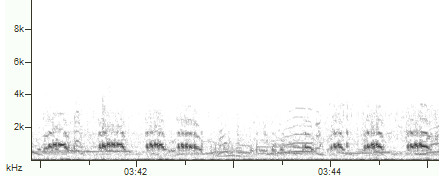

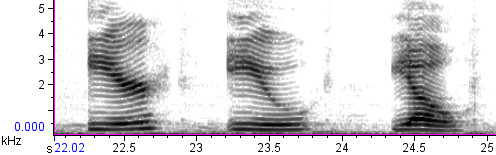

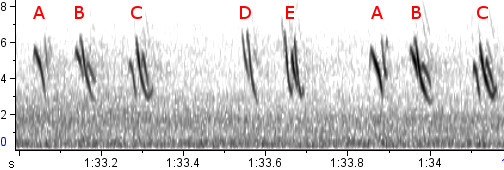

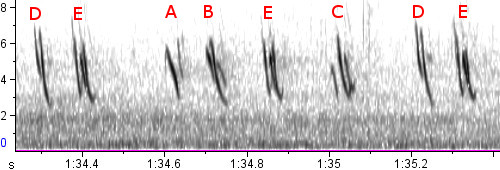

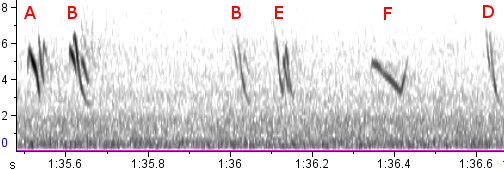

Now that you’ve wrapped your head around what the “Least” subspecies sounds like, check out these recordings of arizonae:

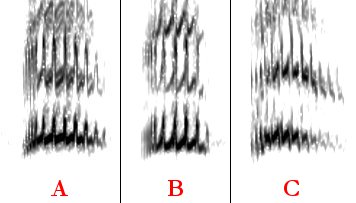

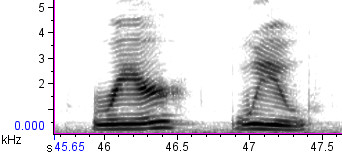

I’ve listened to all these recordings several times through, pored over spectrograms in Raven, and looked through Peter Beck’s 1996 thesis on the songs of “Least” Bell’s Vireo. Maybe there are some diagnosable differences in song, but I’ll be darned if I can find them. On current knowledge, the subspecies are indistinguishable by ear, and that’s the way it’ll stay for now.

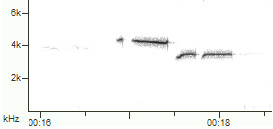

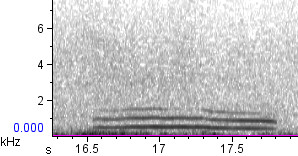

Interestingly, there are a few differences in the calls from the different subspecies posted on Xeno-Canto, but I strongly suspect those are due to differences in the state of agitation of the individual birds, and not indicative of their genetic makeup. Sorry, Elisabeth — I got nothin’.

(If you got somethin’, please leave it in the comments!)