The Changes Are In

It’s July, and that means it’s time for the annual update to the American Ornithologists’ Union Checklist. That means the splits I blogged about recently are now official.

Besides the high-profile splits of Winter Wren, Whip-poor-will, and Black Scoter, the checklist committee also did some major rearranging of scientific names, splitting a number of genera and reassigning several species to a new genus. They do this whenever scientific studies (usually DNA studies these days) make it clear that birds currently classified in the same genus are not, in fact, each other’s closest relatives. Although most such splits this time around were based on DNA evidence, vocalizations also support most splits. Below we’ll take a quick survey of what’s changed and how audio was involved.

Species split

- Winter Wren is split into three species: Pacific Wren (Troglodytes pacificus) in northwestern North America; Winter Wren (Troglodytes hiemalis) in eastern North America; and Eurasian Wren (Troglodytes troglodytes) in the Old World. Vocal differences were important in this split; see my older posts on how to separate Pacific from Winter Wrens by song and call.

- Whip-poor-will is split into Mexican Whip-poor-will (Caprimulgus arizonae) and Eastern Whip-poor-will (Caprimulgus vociferus). Vocal differences were important here as well; see my earlier post on this topic.

- Black Scoter is split into Black Scoter (Melanitta americana) in the New World and Common Scoter (Melanitta nigra) in the Old World. Once again vocal differences were key, and once again you can hear them in an earlier post.

A couple of Latin American trogon species, the Greater Antillean Oriole, and the Elepaio of the Hawaiian islands were also split.

Changes in Genus

“Brown” Towhees Move to Melozone

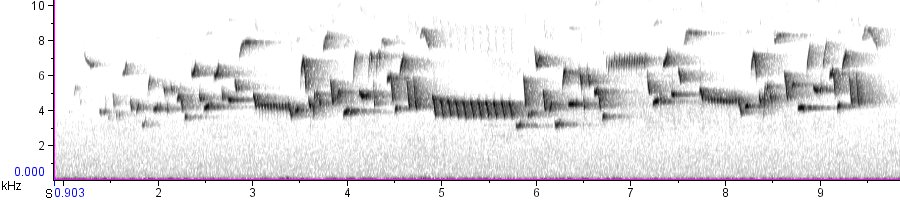

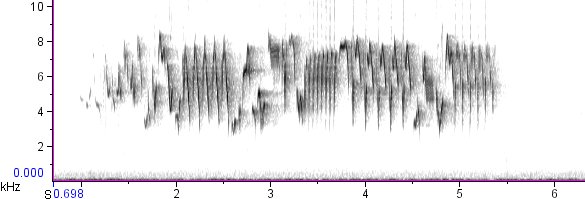

Abert’s, Canyon, California, and White-throated Towhees will move from the genus Pipilo to Melozone, where they will join the Rusty-crowned, White-eared, and Prevost’s Ground-Sparrows. This genus split makes sense when you listen to the songs: the “brown” towhees sing with unmusical high-pitched trills and squeals that are very different from the rich, musical series of the “true” towhees.

“True” Towhees Remain in Pipilo

These species usually sing songs composed of 2-4 series of fairly musical notes — sometimes highly musical notes. Some of them can be confused with each other, but rarely would they be confused with any of the “brown” towhee songs.

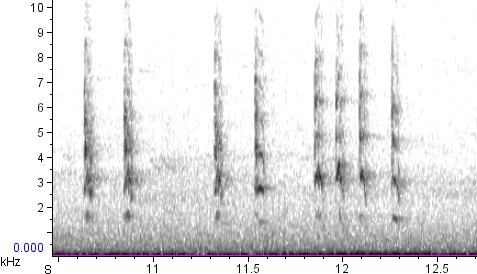

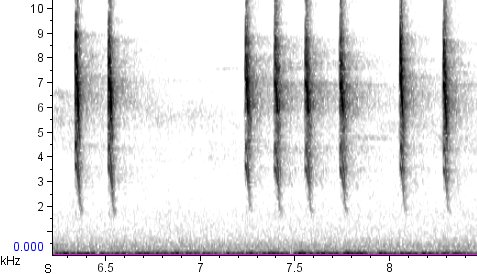

“Nashville” Warbler complex moves to Oreothlypis

Nashville, Virginia’s, Lucy’s, and Colima Warblers will move to the new genus Oreothlypis, along with the Orange-crowned and Tennessee Warblers. This group is characterized by songs that are composed of 1-3 rapid (but not buzzy) trills. The similarities are obvious on the spectrograms and to the ear:

Blue-winged and Golden-winged Warblers remain in Vermivora

These two species, plus their extinct relative the Bachman’s Warbler, remain in Vermivora. All three are linked vocally by their very buzzy songs, quite similar to one another but quite different from those of the species leaving the genus.

Bachman’s Warbler songs can be heard at the Macaulay Library: [1 2]

Crescent-chested and Flame-throated Warblers move to Oreothlypis

This is one change that doesn’t seem to be supported by vocalizations. These two Central American species were formerly in the genus Parula with (surprise) the parulas. And their songs sound very like those species — high and buzzy — not at all like the songs of the other bird moved to Oreothlypis.

These embedded iframes are great, but they take up a lot of space, so we’ll continue on this theme tomorrow.