What Gulls Say

Gull enthusiasts are weird. They hang out at landfills. They go to the beach when it’s freezing cold, or just to see what’s in the parking lot. They’ll stare at a single bird for hours, puzzling over insanely minute details – the precise shade of gray on the back as measured by the Kodak gray scale, the age and condition of individual feathers, and even (I am not joking) the color of the inside of the bird’s mouth. When it comes to identifying a mystery gull, they look at everything; they ignore nothing.

Except vocalizations.

Gulls have voices, but you’d hardly know it from reading the identification literature.

In all the thousands and thousands of words written each year about gull identification by experts on the ID-Frontiers listerv, vocalizations are mentioned approximately never. P.J. Grant’s classic book Gulls: A Guide to Identification contains not a single mention of voice. Howell & Dunn’s Gulls of the Americas refers to voice only in passing, in the introduction, and omits it from the species accounts. Olsen & Larsson’s authoritative Gulls of Europe, Asia and North America briefly mentions only a few sounds for each species.

I think the general neglect of voice can be explained by three factors:

- Gull sounds are variable. Two individuals of the same species may sound very different.

- Gull sounds are plastic. Two calls from the same bird may sound very different.

- Gull sounds are poorly understood.

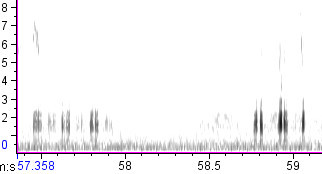

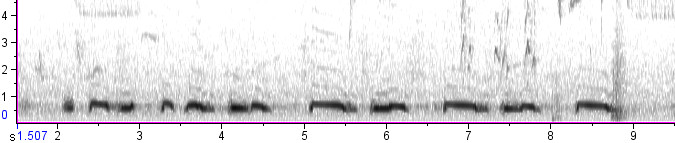

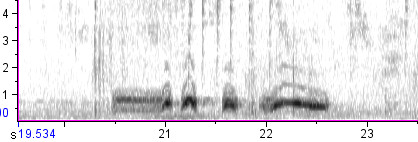

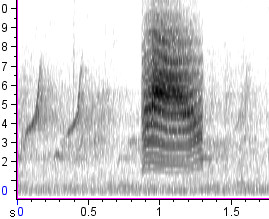

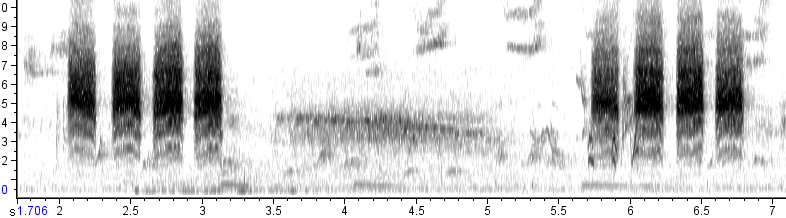

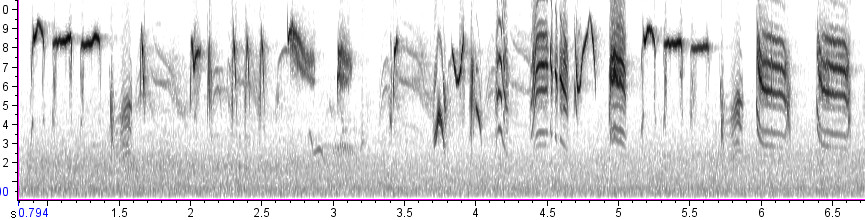

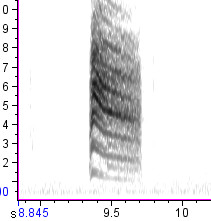

Those first two problems are not to be underestimated. Until recently, my main experience with gull sounds came from attempting to record some Ring-billed Gulls fighting over some bread I’d thrown them. I was astonished (and frankly intimidated) by the huge variety of sounds I heard. They whistled, they squealed, they barked, they bleated, they gargled:

I really couldn’t make sense of it. Could these vastly different calls be merely variations on a simple-minded expression of hunger? I began to worry that gull sounds might well be too variable to be of much use in identification.

Then I had another experience that changed my perspective.

The Western Gull Rosetta Stone

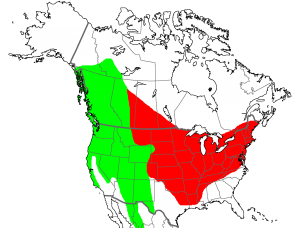

Last month I attended the Western Field Ornithologists’ Conference in Petaluma, California, where I tracked down local gull expert and field guide author Steve N. G. Howell for an answer to my burning question: “Where can I record gulls around here without too much ocean noise?”

After some thought, Steve sent me to the parking lot at Stinson Beach. It was just what I was looking for: an open, public area only a few yards from the ocean, but sheltered from the surf noise by a nice high earthen berm. I got there early in the morning and found myself alone in the parking lot with a couple dozen gulls of two species (Heermann’s and Western). Conditions were good, but even so, I was unprepared for the show.

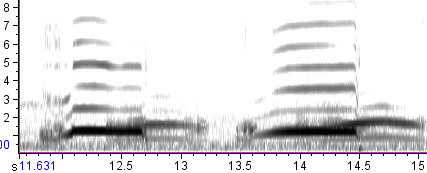

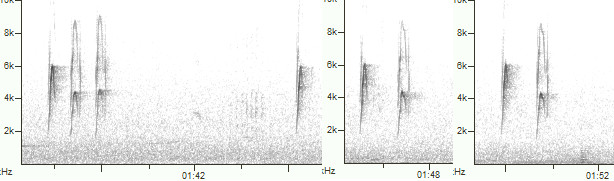

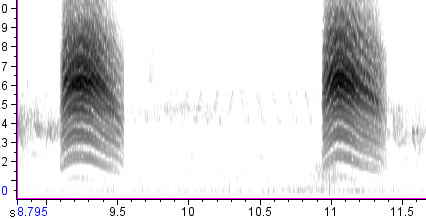

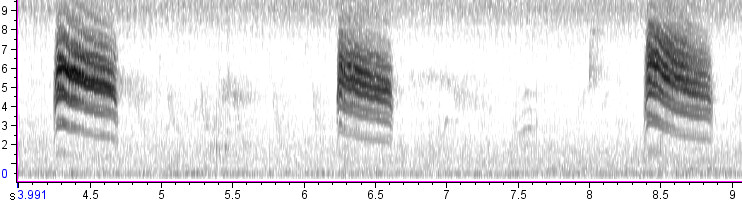

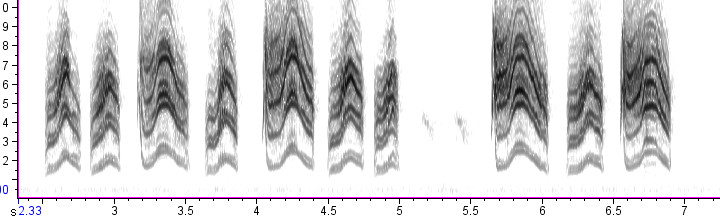

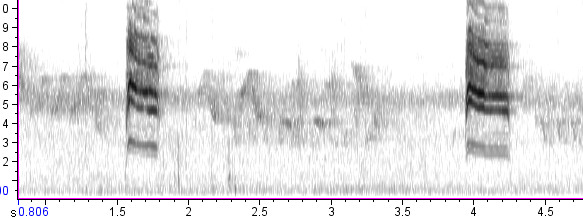

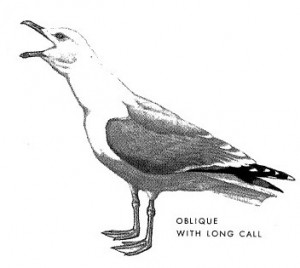

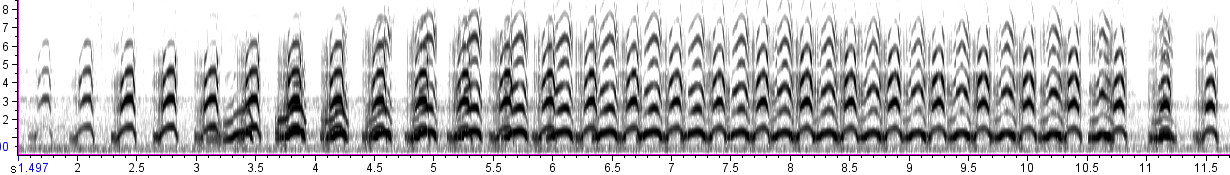

It started when a pair of Western Gulls broke into a Long Call Duet. Standing close together, they bowed their heads down once toward the pavement and then stretched their necks out at a 45-degree upward angle for the rest of the call:

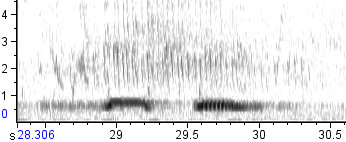

Immediately, both birds transitioned into a slow series of long, rising wails, much like the sounds of a peacock, as they strutted around the parking lot in parallel, necks fully extended, bills pointed downward:

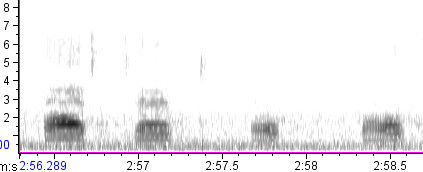

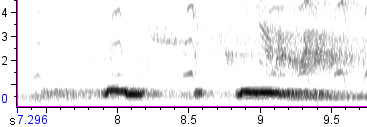

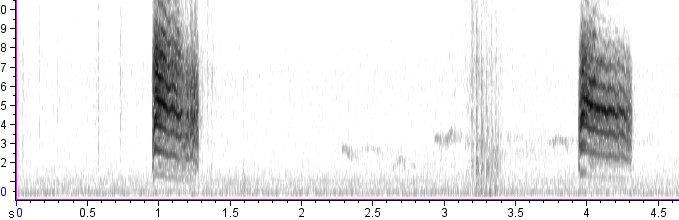

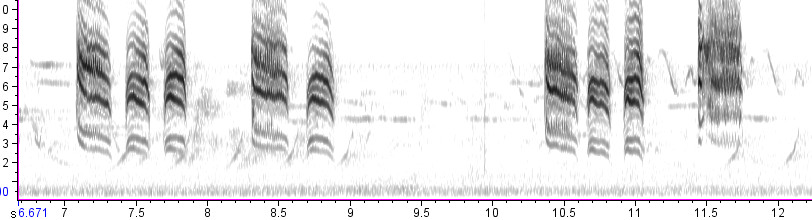

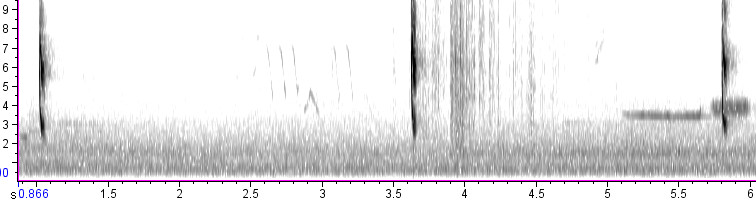

Then one bird picked up some leaves and twigs in its bill. It crouched down on the ground as though it wanted to begin building a nest scrape, or perhaps as though it were soliciting copulation. It began giving short, quiet grunts while its partner continued to wail occasionally:

|

|

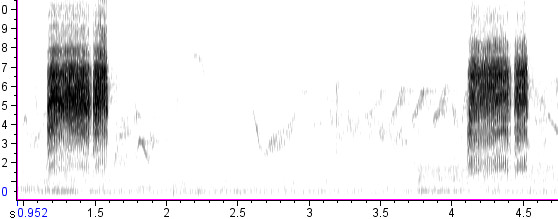

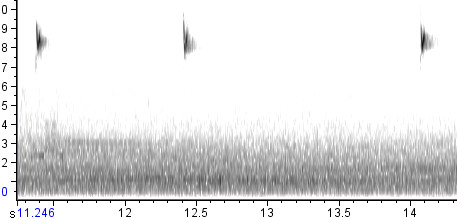

Just when I thought the show couldn’t get any better, a third Western Gull flew in, and one member of the duetting pair charged off to confront it. The two locked bills in an intense tug-of-war, wings out for balance, giving a soft but threatening chuckle vocalization:

Fans of Alfred Hitchcock may remember that chuckle — it’s the sound dubbed into The Birds whenever the Western Gulls gather ominously. (Hitchcock added a little echo, to make it even spookier.)

When I got home, I discovered I’d recorded over half an hour of this remarkable show, and an additional ten minutes or more of myself narrating behavioral notes into the microphone. It was the highlight of my entire trip to California.

Surprise, Surprise

The distinctiveness of each of the sounds I recorded, and the fact that each was obviously tied to a different social context, gave me a whole new view of gulls and their vocalizations.

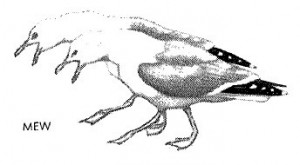

Because I made those detailed notes on the posture and context of each sound, I was able to match each one up pretty well with the established literature on gull vocalizations (especially the pioneering work of Niko Tinbergen 1960a, 1960b). The peacock-like wail is called the “Mew” call; the grunting accompanies the “Choking” display; and the chuckle is known as the alarm call. Clearly, at least some of the time, gulls are more than just screaming kleptomaniacs. They are capable of wonderfully complex and evocative social communication.

Flirting or Fighting?

My original hypothesis was that I was observing courtship behavior, but this may actually have been an aggressive territorial encounter, perhaps between two males. All of these displays are used in both aggression and in courtship.

Supporting the courtship hypothesis is the fact that this duetting pair never resorted to fighting. When a third bird arrived, one of the displaying pair fought it off, while the other member of the pair looked on in agitation, giving a very long Long Call sequence. When the third bird was driven off, the pair display resumed immediately between what I took to be the original two birds.

Furthermore, this pair’s strutting dance didn’t seem restricted to any territorial boundary. Instead it rambled over hundreds of yards of parking lot, seemingly at random. Every once in a while the two birds would break off and drift apart, silently or with a few chuckle calls. Once, when the two birds were widely separated, one of them crouched without apparent provocation and started giving a series of “Choking” grunts. The second member of the pair immediately began walking towards it from a hundred yards away, taking up the wailing “Mew” cry when it got close. The entire episode seemed to have the air of solicitation rather than confrontation.

Supporting the territorial interpretation, however, is the fact that it was late September. Western Gulls aren’t supposed to start pairing up for mating until January at the earliest. I couldn’t tell the sex of the birds. Although I kept expecting copulation to occur, it never did. Nor did I see any of the unambiguous pair-bonding displays, such as the regurgitation of fish, which is the gull equivalent of recreational sex.

Gulls of several species have been reported to defend winter feeding territories, and that could have been what these birds were doing. Perhaps a local breeder was fending off an interloper in search of winter turf.

The Take-Home Message

Somewhere near you, right about now, a pair of gulls is about to engage in a loud and conspicuous display. They’ll do it wherever they find themselves — in a park, on a city street, at the grocery store — with little regard for what’s around them. You’ll be able to walk right up to them with your camera, your smartphone, your recorder.

Do it. Take notes on what you see. Post your resulting pictures/video/audio to Flickr/YouTube/Xeno-Canto. Then drop me a line.

We don’t know enough about gull displays, especially not in fall and winter. Most research on gulls has taken place on the breeding grounds, and it’s possible that we don’t know about autumn courtship because we haven’t been paying attention. We also don’t know much about identifying gulls by voice — but all we need to do is listen. By sharing our observations online, we have the power to learn a ton. Let’s give it a try.