A Hybrid Hummingbird?

Rich Hoyer has posted photos and spectrograms of an apparent Calypte x Archilochus hummingbird at his blog this morning. He’s also posted a sound file in the “mysteries” section of Xeno-Canto.

I’m no expert in the visual identification of female hummingbirds, so I can’t make too many comments on his photographs, but the vocalizations of hybrid birds are of long-standing interest to me, so his sound files and spectrograms certainly got my attention. A morning’s investigation convinced me that the sound file he posted does indeed provide good evidence that the bird at his feeder could be a hybrid, probably the progeny of a Black-chinned Hummingbird and a Costa’s Hummingbird.

|  |  |

| Female Black-chinned Hummingbird, Moab, Utah, June 2006. Wikimedia.org (Creative Commons 3.0). | Male Costa's Hummingbird, 16 April 2009. Photo by Chris Fritz (Creative Commons 2.0). |

According to the excellent Hybrid Hummingbirds page at Trochilids.com, the hybrid combination of Black-chinned x Costa’s (which seems most likely for Rich’s bird given his comments on its plumage) was documented by Short & Phillips (1966), so if the bird is confirmed to be of that mix, I believe it would be the third documented such hybrid and the second known female.

Rich has already posted some spectrograms over at his place, but I’m going to go ahead and supplement his with some of my own. Since the fine details of hummingbird chips are pretty fine indeed, I’ve zoomed these things in MUCH farther than usual and widened the filter bandwidth for better time resolution.

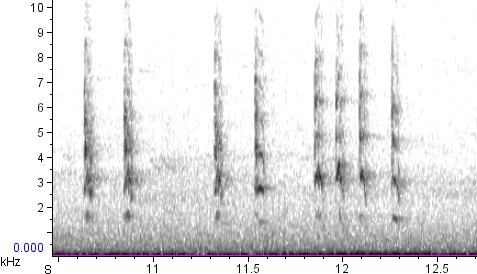

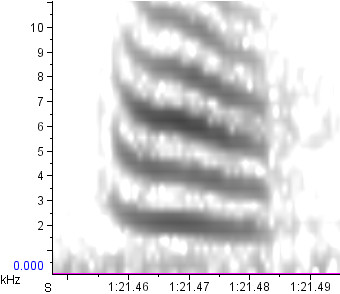

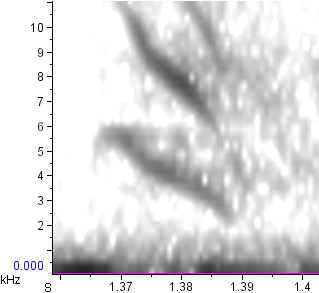

First, here’s the typical chip of a female Black-chinned Hummingbird:

Note the downslurred intonation and the strong partials, with the third one strongest. If this call lasted 20 times longer, we would hear its nasal tone quality. Since it’s so brief, we just hear a high-pitched, fairly clear downslurred “squeak.”

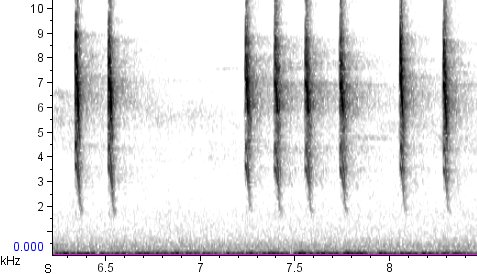

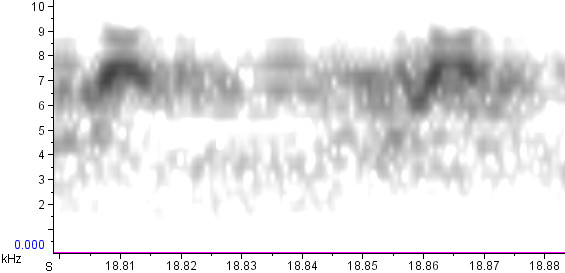

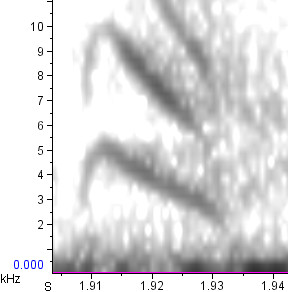

Here’s the standard call of the female Costa’s Hummingbird, first at the same zoom level as above, then zoomed out to a slightly more sane perspective:

(Click here to listen to the audio at the Borror Lab’s website. It takes a bit for the bird to call.)

Obviously, the calls of Costa’s and Black-chinned Hummingbirds are extremely different on the spectrogram, and they can even be distinguished easily by ear with experience. As Rich’s spectrograms show (and my research has so far corroborated), Costa’s is the only hummingbird in the Calypte/Archilochus group with an upslurred call note (actually an overslur, as you can see above) — and the upslurred beginning of the Costa’s call is often perceptible to the ear. Black-chinned, Ruby-throated, and Anna’s all have perceptibly downslurred calls.

The calls of Black-chinned and Ruby-throated are by far the lowest-pitched, with many harmonics visible; they are less sharply inflected and therefore more musical than the calls of Anna’s Hummingbird, which start at a far higher pitch (around 9 kHz) and descend much more quickly, giving them a less musical “ticking” quality.

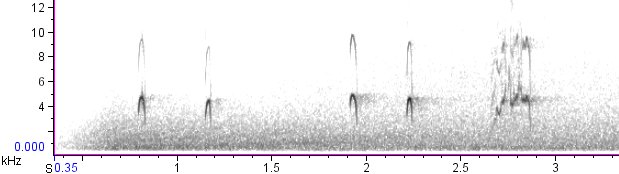

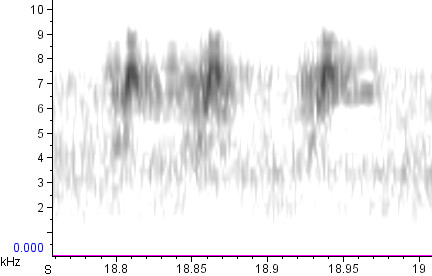

The hybrid at Rich’s feeder has downslurred calls with many visible harmonics, much like a Black-chinned Hummingbird, except higher-pitched and more sharply inflected:

(again, click here for Rich’s audio at Xeno-Canto.)

By itself, the higher pitch and sharper inflection (noted by Rich’s keen ears as “too high and percussive for Black-chinned”) didn’t at first convince me the bird was a hybrid. A careful reading of Rusch et al. 1996 finds mention of a rather similar vocalization from Black-chinned Hummingbird, which the authors called the “E note,” but even this note is not high-pitched enough to match the hybrid, and it is apparently never given outside the complicated chatters that hummingbirds make when sparring with each other. The same apparently holds true for Ruby-throated Hummingbirds (Rusch et al. 2001). So Rich’s recording is at least suggestive of hybridity.

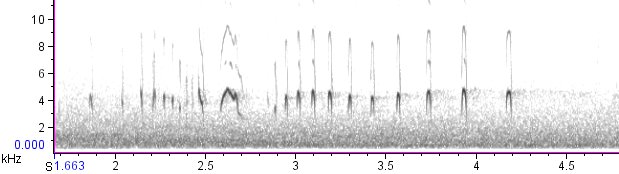

But here’s something even more interesting: not every note on Rich’s recording is identical. Most of the calls on the cut actually start with a slight but noticeable upslur:

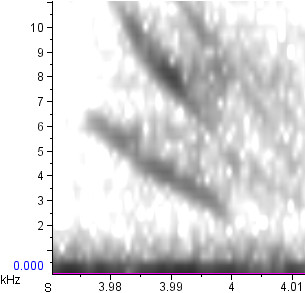

And sometimes it is very pronounced:

Although I don’t think it constitutes proof, this definitely suggests to me that the bird has some Costa’s Hummingbird genes. Rich, I think it’s time to contact your friendly neighborhood hummingbird bander. And keep that microphone running!