AOU Checklist News!

The North American Checklist Committee of the American Ornithologists’ Union has published the results of its deliberations on the first round of proposed changes from 2009, and it has updated the slate of proposals currently under consideration. Here’s a quick summary of the changes that affect species splits north of Mexico. (I won’t get into all the changes to scientific names, even though those topics are just as interesting in my opinion — you can click through to read about those yourself.)

Proposal accepted

This split will become official once the next checklist supplement is published in the July 2010 issue of the Auk.

- Split Pacific Wren from Winter Wren. As I reported earlier, this split did indeed pass, and unanimously at that. However, note that the names “Pacific Wren” and “Winter Wren” are not final. The committee is considering an addendum to the proposal that would split eastern North American birds from Eurasian birds and change the names of the American species to “Western Winter-Wren” and “Eastern Winter-Wren.” Stay tuned.

Proposals rejected

In most cases, a 2/3 vote of the committee is required for a proposal to pass. These proposals failed to muster that level of support:

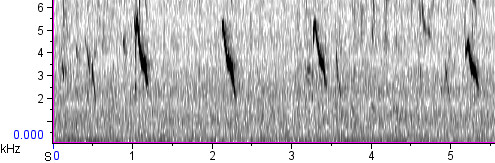

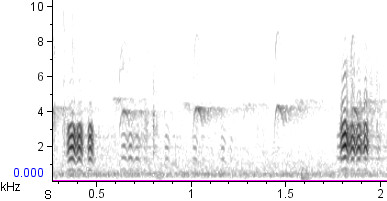

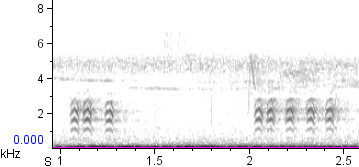

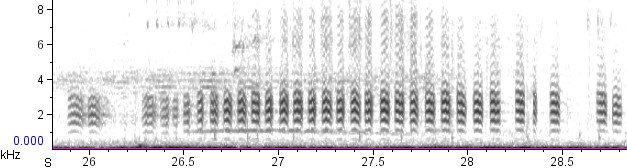

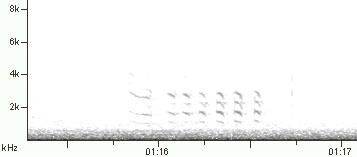

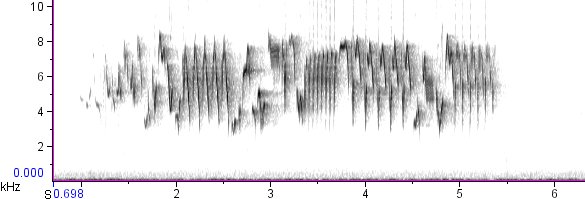

- South Hills Crossbill. The proposal to split South Hills Crossbill (Type 9) from Red Crossbill failed on a vote of 6 “yes” votes to 5 “no” votes, with three of the “no” voters indicating that they would be open to changing their minds if presented with more data. Two of those voters preferred to deal with the North American Red Crossbill complex as a whole, rather than splitting one type at a time, piecemeal. Thus, most of the committee appears to accept that the different call types of Red Crossbill are likely good species, but I think it may be a while before those species appear in your field guide.

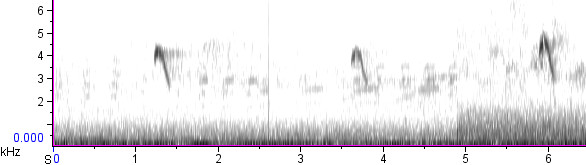

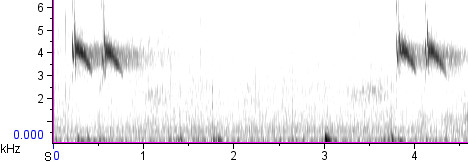

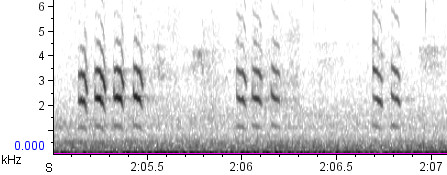

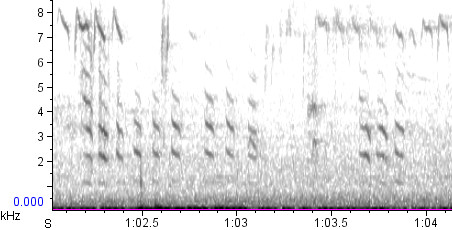

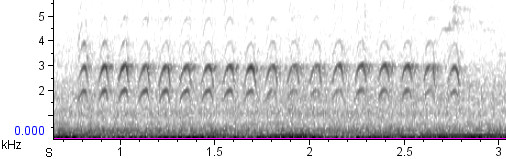

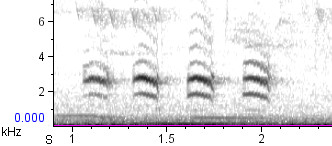

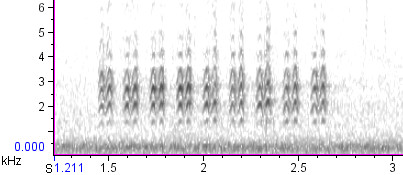

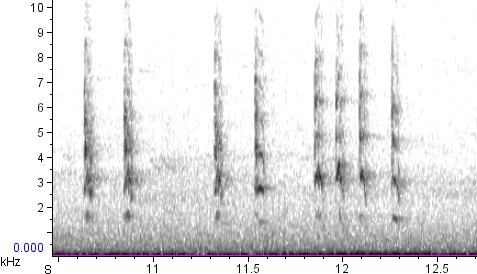

- The split of Western Scrub-Jay. The proposal to split the interior “Woodhouse’s” Scrub-Jay (woodhousei) from “California” Scrub-Jay (nominate californica) failed on a vote of 7 “yes” votes to 5 “no” votes. Many members of the committee felt that more data were needed from contact zones. The tagalong proposal to split the southern Mexican subspecies sumichrasti into yet a third species gained even less committee support. Vocal differences between woodhousei and californica have been reported, and you can expect those differences to be discussed in a future post on this blog.

New proposals

The checklist committee never sleeps. The following splits of North American species are now under consideration:

- Split Black Scoter (Melanitta americana) from Common Scoter (Melanitta nigra). I wrote about this split recently. This proposal was originally submitted in 2006 and failed to pass at that time, but the recent publication of Sangster (2009) has revived it. Personally, I think it’s a clear-cut split, but we’ll see if the committee agrees.

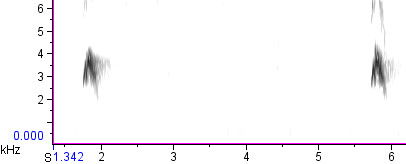

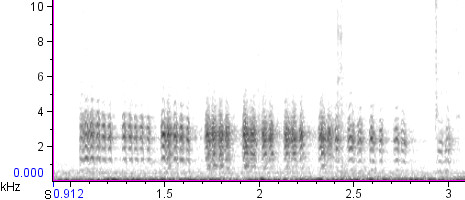

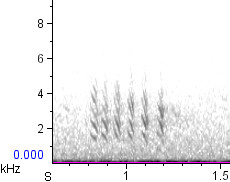

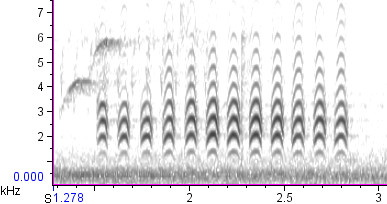

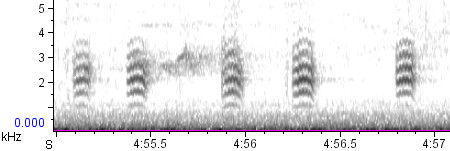

- Split Curve-billed Thrasher (Toxostoma curvirostre) into two species: the western palmeri group and eastern curvirostre group. The proposal makes no recommendation regarding the resulting English names. The proposal cites various genetic data, which I won’t comment on, but it also cites vocal differences, including differences in calls. I’m a little skeptical of these differences, but I’ll investigate them in the future and report back on what I find.

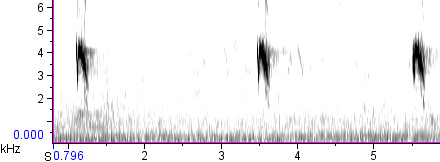

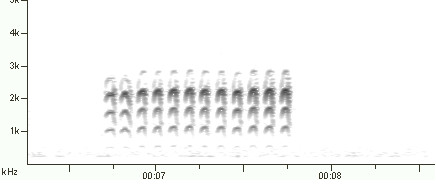

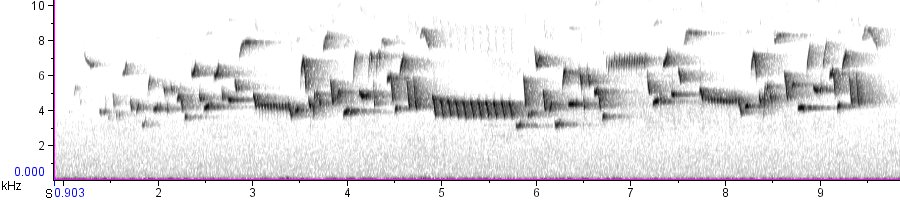

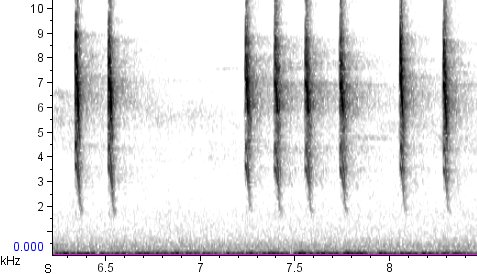

- Split Whip-poor-will (Caprimulgus vociferus) into a nominate eastern species and the southwestern arizonae species, on the basis of subtle but easily diagnosable differences in song, differences in egg coloration, and (most importantly) a hot-off-the-presses study demonstrating that the vociferus and arizonae groups may be as genetically distinct from one another as either is from the Dusky Nightjar (C. saturatus) of Costa Rica and Panama. I haven’t been able to track down the article text yet, so I can’t say what I think of it.

As you can see, vocal differences are playing an ever-more-prominent role in taxonomic decisions. Look for more on this topic from me in the future.