Splitting Mountain Chickadee

The AOU’s North American Checklist Committee has posted a set of proposals currently under consideration. The biggest surprise is a proposed split of Mountain Chickadee into two new species:

- Gambel’s Chickadee (Poecile gambeli) in the Rocky Mountains and the Great Basin, including populations in eastern Washington and Oregon;

- Bailey’s Chickadee (Poecile baileyae) in the Sierra Nevada, the Cascades, and the California coastal mountains.

Until the AOU proposal appeared, a potential split of Mountain Chickadee was not even on my radar screen. However, two different molecular studies have found evidence that the two groups of chickadees are genetically quite distinct, and they apparently differ slightly in appearance, with “Gambel’s” Chickadees having a slightly longer tail, slightly more white above the eyes, and a faint buffy tinge to the underparts and back.

|  |

| "Gambel's" Mountain Chickadee, Sandia Crest, NM, 3/26/2008. Note the buffy underparts and broad eyestripe. Photo by J.N. Stuart (Creative Commons 2.0). | "Bailey's" Mountain Chickadee, Yosemite National Park, CA, 11/24/2007. Note the gray underparts and narrow eyestripe. Photo by Yathin (Creative Commons 2.0). |

In addition, the proposal mentions song differences. Sadly, it provides scant evidence for this claim. Here’s the entire discussion of vocalizations:

Miller (1934:163) reported on song differences that he detected between Mountain Chickadees from southern Utah (wasatchensis) and from California (abbreviatus or baileyae): “I note repeatedly that the songs of this chickadee [wasatchensis] consists of two groups of notes separated by three or more half tones of pitch. In contrast to this type of song are those of the races P. g. baileyae and abbreviatus in which the greatest interval of pitch with rare exceptions is no larger than one whole tone.”

This is flimsy evidence indeed. The difference in pitch interval that Miller noted could potentially be significant, but it’s only one metric by which to measure the complex matrix of geographic variation in Mountain Chickadee vocalizations. Mountain Chickadee’s vast geographic range comprises a balkanized patchwork of dozens of different dialect regions, as one would expect in a bird that learns its song. Miller was a single naturalist noting a single difference between just two or three of these dialects, in an era before sound recording and spectrographic analysis.

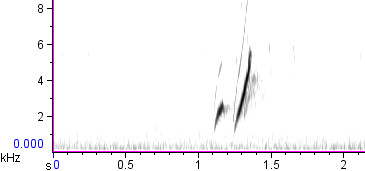

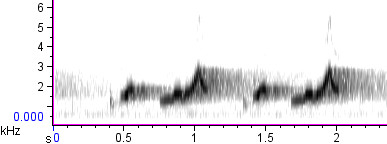

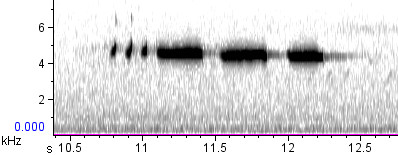

Furthermore, the evidence I’ve found so far doesn’t even corroborate his original observation. Here’s the most common dialect variant of “Bailey’s” Chickadee, the version of Mountain Chickadee song most likely to be heard all throughout the Sierra Nevada:

(Click here to listen to the recording at the Macaulay Library.)

Many observers in the region transliterate this (and similar songs) as “cheese-burger,” although there’s actually a short extra note in front of the “cheese” in most parts of the Sierra. The “cheese” and “burger” parts of the song are separated by about a full step on average, with slight variations from place to place [1 2 3 4 5]. So far, so good — these recordings are mostly in line with Miller’s observations.

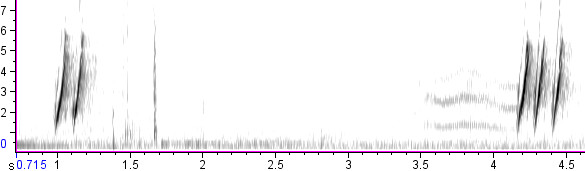

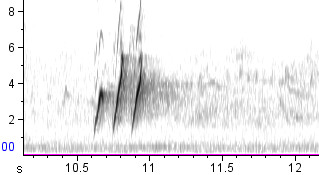

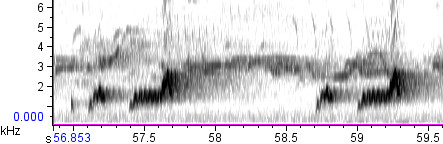

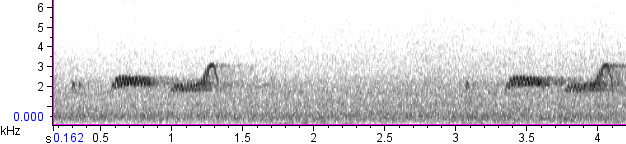

But the wide pitch intervals that Miller reported from southern Utah are certainly not representative of most “Gambel’s” Chickadees. In this Borror Lab recording from northern Utah, the notes are quite close to one another in pitch, each about a half step lower than the last. And most Mountain Chickadees in Colorado sing nearly monotone songs, like in this typical example:

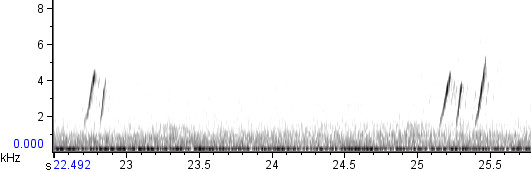

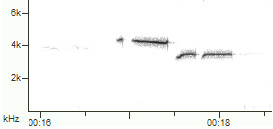

Here’s an example of a “Gambel’s” Chickadee from British Columbia that sings a songtype not unlike the Sierra Nevada “Bailey’s” song:

Meanwhile, here’s a “Bailey’s” from the heart of the Sierra Nevada that barely changes pitch at all, and here’s a “Gambel’s” from Wyoming that apparently sings two songtypes, one with a large pitch change and another that’s nearly monotone.

Perhaps the genetic data is clear enough to warrant a split of Mountain Chickadee, and perhaps vocalizations do differ systematically — they may even act as an isolating mechanism between the two groups. But a far more in-depth study would be needed to demonstrate this. On the basis of the evidence presented in the AOU proposal, I can see no reason at this time to add “vocalizations” to the list of reasons for the split.