Recordist Profile: Andrew Spencer

I’ve been bugging my old buddy Andrew Spencer to send me a recordist profile for months now, but until this week he was too busy slogging around South America. Now he’s on a stateside break until July, when he’s headed back to the Bird Continent to take up residence as a professional birding tour guide.

Ten years ago Andrew and I used to take off on birding trips all weekend every weekend, not to mention most days after school. After I caught the recording bug, it wasn’t too long before Andrew caught it too. Now, he’s the top contributor to Xeno-Canto, with 2500+ of his recordings online.

I’m pleased to say that I’ve added Andrew as an Earbirding author, so you’ll be seeing occasional posts by him on this site from now on. I figured it was a good idea to introduce him to his audience before handing him a keyboard — hence this author profile.

Here’s what Andrew has to say about himself and his recording.

I started watching birds when I was about five, but didn’t start recording until after my first trip to South America, to Ecuador in 2006. While there I realized that the ability to record birds in the tropic was absolutely fundamental to fully enjoying South American birding, and as soon as I got back I bought my first recording rig.

In the few years since then I have become ever more deeply obsessed with recording…what at first was something to help call unknown birds in and document unknown sounds for later identification became a quest to record as many species, song, and call types as I could. As a result I have traveled around much of the US and South America recording birds.

Since I started recording I have used a number of different recording rigs, in the following chronological order:

Sony HD mini-disc with a Sennheiser me66 shotgun mic

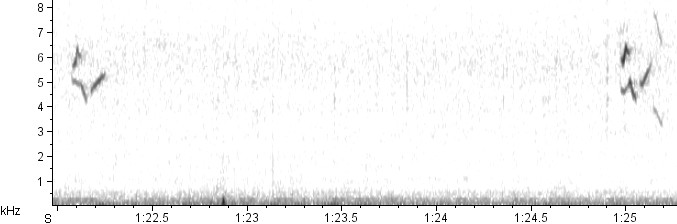

This was my first rig, and a basic yet ultra portable setup. The minidisk recorder did a decent job in terms of recording the sound, but had several serious drawbacks, chiefly the lack of ability to manually adjust the gain. [listen to a Yellow Rail Andrew recorded with this rig]

Oade modified Marantz PMD660

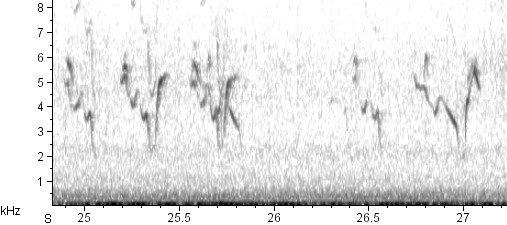

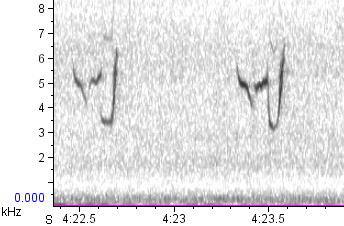

I used this recorder with both my shotgun mic and with a Telinga Parabola I later purchased. Of all the recorders I’ve used this was by far my favorite; it had remarkably clean and powerful preamps, approaching those of high-end recorders. It did have some durability problems, and repeated exposure to high humidity in the tropics caused problems with the output lines. [listen to a Tepui Wren recorded with Marantz & shotgun, and a Golden-cheeked Warbler recorded with Marantz & parabola ]

Fostex FR2-LE

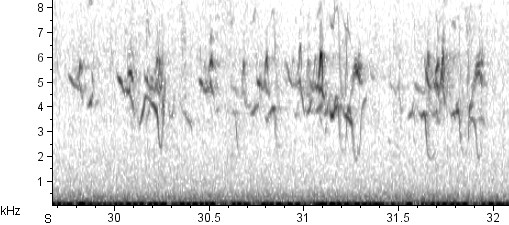

My current recorder, I got this on short notice to replace the malfunctioning Marantz. As a whole it does a decent job, but the preamps are noticeably noisier and less powerful that the Marantz, and the rig as a whole is less durable in my opinion. I mostly use a Telinga Parabola and a Sennheiser me62 omnidirectional microphone with the Fostex, which produces acceptable but usually not stellar results. [listen to a Peruvian Plantcutter recorded with Fostex & parabola]

I use a couple of different recording styles while in the field, depending on where I am and who I am with. In North America I usually have a small list of targets that I want to record, and if I find a vocalizing bird I stick with it for a long time trying to get different sounds out of it. Other times, especially if I am on a trip to an area I don’t go to much or with non-recordists I will record a bird making noise but move on fairly quickly to the next species.

I tend not to use headphones while recording, even with the parabola. While using headphones does allow one to pinpoint a singing species with more precision I find that it also makes it harder to hear other birds singing around you, and the process of putting on an removing the headphones both eats up time and is really quite annoying. With practice I feel it is possible to pinpoint a target with a fair degree of accuracy and by watching the meters on the recorder. Since I don’t use headphones I also rarely use the wind coat for that parabola, since this allows me to look through the clear dish and at the bird, if it is visible, and pinpoint it without having headphones.

Unlike some recordists I am a big believer in post recording editing. Typically I will filter out low frequency rumble if it doesn’t overlap the target signal, amplify the recording if it is very quiet, and if necessary remove background talking and handling noise. For editing sounds I recommend Raven Lite, available free from the Macaulay Library, and for more advanced editing Adobe Audition.